When Christi Belcourt was 27, she was given a pair of Metis Mukluks. A native Michif (Metis) living in Ontario, Canada, she had, for a few years, been learning traditional ways of thinking and seeing the world from native elders who had taken her under their wings. These relationships and teachings had helped her move from a dark place of dislocation and pain. When she received the Mukluks, she was intrigued by the beadwork on them and decided to try to "paint" the design. But, as she says, she learned two important things from her first attempts:

Number one, I didn’t know enough about plants to be painting them, and number two, I didn’t know enough about beadwork to paint it either.”1

Learning

So, she began to study both plants and the traditional beadwork of the Metis. “Every plant I came across, I looked at it in detail, I spoke to it, I asked it ‘how did you grow like that?’ My love for plants deepened further and further, and I began to understand what people meant when they said, “we are all connected.'”

Referred to by many as the “Flower Beadwork People,” the Metis use a preponderance of flower designs in their beadwork and embroidery and Belcourt learned all she could about this art form.

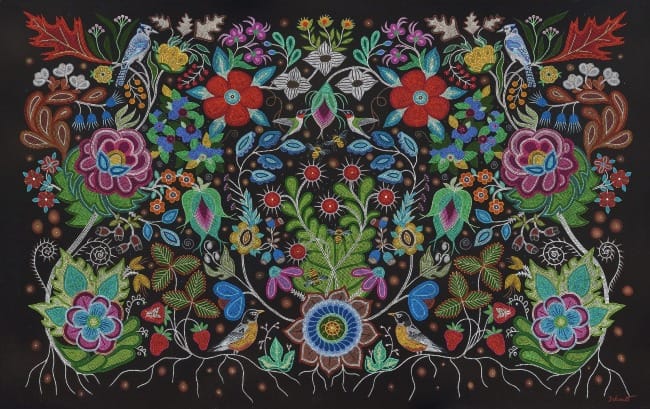

Belcourt's "bead" paintings are made by painting thousands of dots, formed by dipping the point of a stylus, paintbrush or knitting needle into paint and then onto the canvas. The resulting painting resembles the Metis beadwork Belcourt so admires. (See the beadwork on the left and the painting on the right, below).

Beadwork on left, Detail of Belcourt painting on right

Relationship

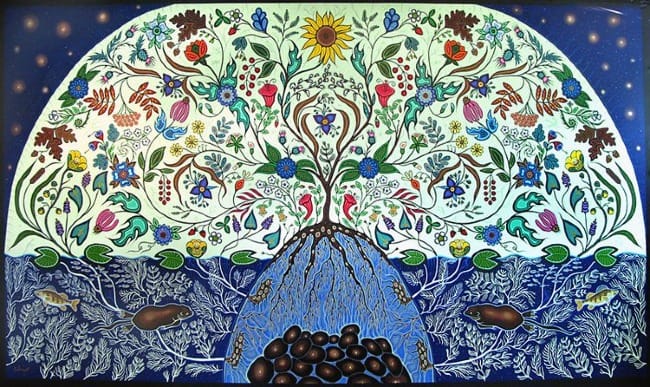

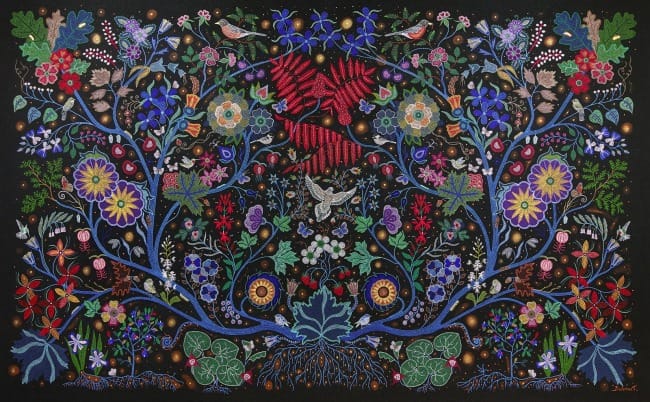

Her paintings often incorporate dense and colorful paintings of specific plants and animals, intertwined with each other, showing their interconnectivity, often with the right side and left side symmetrical in design. This symmetry shows us something about the way the world exists—balanced, centered, and patterned as a whole design, not in separate bits and pieces. These paintings are often very large (the one pictured below is 6.75 feet by 8.5 feet), giving a feel to the viewer of the largeness of the world and its natural systems. Often the captions beneath her pictures tell Belcourt's story about that particular picture.

Belcourt's paintings show her deep concern and interest in the nurturing relationships that exist between species that share the earth. These "kinship networks are place-based and non-capitalistic."

We are not separate from anything, we are born connected to the earth, with the capacity to love, to be kind, to be generous, to be gentle. 2

“The sacred laws of this world are of respect and reciprocity. When we stop following them, we as a species are out of balance with the rest of the world.” 3

“In Indigenous ways of thinking and knowing and being, the concept of walking softly on the earth is not a quaint thought. It’s a practical thought about preserving life on the earth.” 4

Care

If taken to heart, this view of interconnectedness affects how we live. If all beings are related, there is responsibility to consider the way we walk and live in this world. If, we see, for instance that water connects all the creatures in the way that is pictured below, we must see how important it is to consider the needs of other creatures as well as our own, rather than seeing these issues as isolated "individual" or even just a "human" issues. The whole earth is dependent upon water, and we must act accordingly.

When Belcourt talks about her work, she mentions kindness as the most important action we can take. In a world permeated by violence—against people, animals, land, the earth, kindness, as Belcourt sees it, is the antidote.

What is the antidote to greed? Generosity. What is the antidote to being mean? Kindness. Kindness is an action that people can take in their daily life...When you’re kind to the waters, you don’t pollute. When you’re kind to the Earth, you don’t throw things out your window and pollute.

And again,

Human beings have been led to believe that we’re at the top of this pyramid, that we are dominant over the Earth, that the Earth is here for our taking, and we’ve commodified everything. When we switch our thinking into believing that the water is alive, that the trees have their own life and their own territories, that the animals have their own territories, and when we start to walk really gently and softly on the Earth because we see this Earth as a sacred living being, then it changes and raises up the consciousness of how we need to be on this Earth. So less is truly more. 5

Living It Out

The painting above demonstrates the activist nature of her paintings. In The Wisdom of the Universe, we see plants and animals that are listed in Canada as threatened, endangered, or extinct, such as the dwarf lake iris, the Karner blue butterfly, and the cerulean warbler. Belcourt's hopes are that her work will remind us of how interconnected existence is on this planet and that we will abandon paths that are unsustainable and find new ones that are sustainable for all who live on this earth.

In addition to her paintings, Christi Belcourt is active in other realms. She was the initiator of the traveling display, Walking with Our Sisters, a commemorative art installation of over 1,763 moccasin vamps (tops) created to remember and honor missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. She has also been active in working for land reparation for native tribes in Canada, and has spoken against practices detrimental to the environmental such as quarries.

But as she says, “Being for something is more powerful than being against something,” says Belcourt. And she is fundamentally for Mother Earth.

The picture above, entitled Quiet Moment of Gratitude, is a lovely picture of someone who has found their place within the world and stops to acknowledge the gratitude for this rediscovered identity. I can see a type of Belcourt herself within this picture, giving thanks for her place and for her discovered knowledge of that place through the paintings that she creates.

“This wondrous planet, so full of mystery, is a paradise. All I want to do is give everything I have, my energy, my love, my labor—all of it in gratitude for what we are given.”

In your faith tradition, have you explored teachings that help you find your right place on earth? Biblical teaching about God's creation of the earth, God's care of the earth and all that is in it, the charge given to humankind to love and tend to the earth, and teachings about loving our neighbors as ourselves, can all orient us to a different view of our connection to the earth. Is there a teaching that has connected you differently to the earth and been life-giving for you? Is there a particular way that you show gratitude for what the earth provides for you?

Louise

I would love to hear from you - contact me directly at info@circlewood.online.

If you would like to hear directly from Christi Belcourt about one of her paintings, check out the video below.