The art of Michael Leunig may appear simple—even childlike—yet it gives us images of ecosystems and connection that remind us of the beauty and joy found within the individual person and within the wider community of creation. His art portrays a compelling and attractive picture of what a world, functioning as a healthy whole, might look like.

A cartoonist, writer, painter, philosopher, and poet, Australian Michael Leunig is significant enough of a figure to have been declared a "National Treasure" in 1999. Much of this public notice comes from the cartoons he has drawn for decades in the Australian newspapers The Age of Melbourne and The Sydney Morning Herald. In addition to this work, (recently discontinued due to a controversial vaccine cartoon), he has a body of paintings, poems, and prayers that bursts with energy and simplicity and reflects his deep love of nature.

Leunig's work incorporates the concept of ecosystem, both the ecosystem of a single person's human nature and the ecosystem of the larger world. Relationships are a recurring theme—between people, between animals and people, between animals, between all that is part of creation. The elements of his paintings are always closely tied to each other—often through the repetition of color and shape, such as can be seen in the painting, Apricot Harvest.

The white shape of the Australian cockatoo, found in the leaves and fruit of the tree, as well as on the ground, visually link the parts of the painting together. That visual linkage helps us see the more comprehensive linkage as well. The relationship of the creatures in the painting have more than a passing acquaintance; they are part of a living ecosystem in which each contributes to and gains from the presence of the other. In the most basic of these interactions, the tree produces fruit which feed the birds and the birds move seeds through their droppings. But in Leunig's paintings, interactions always seem bigger than just the pragmatic element of the relationship.

In some of his work, creatures are so interconnected that it may not even be visually clear where one creature ends and another one begins. The lines curve from one to another as if the artist kept his drawing utensil on the paper as he drew them. The birds, leaves, people, and other creatures are wrapped around each other and, as in Fugue pictured above, intertwined in a dance that leaves no part isolated or completely distinct from the other. The relationship two or more creatures have forms something new—let's call it an ecosystem—that is created and shared in their interactions, something like music that is created by the joining of different instruments or voices. This is Leunig's image for how things exist—not separate, but in joyful relation to each other.

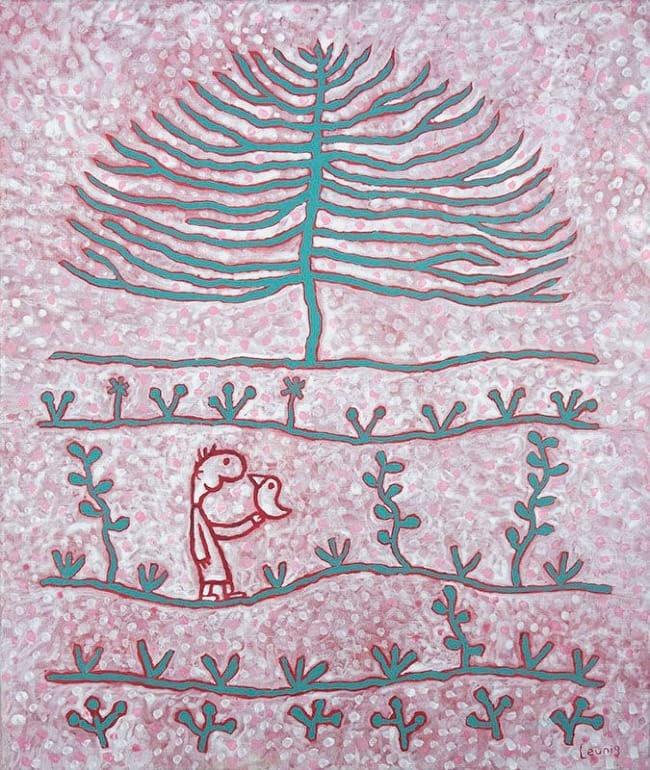

In many of his paintings, the outlines of his different figures physically blur together, emphasizing connection and interplay. In the picture, "Ecosystem," the red outlines of the duck and person run together, as do the strips of plants and ground and tree and ground. The tree isn't separate from the grass; no more is a person separate from nature. They are all connected in the ecosystem of Leunig's paintings.

There is a distinctive air of wonder and imagination in Leunig's paintings, as well as a consistent whimsey. A recurring, but somewhat random, image in his pictures is the duck. He says he first drew it on impulse, thought it improved the work, and liked it enough so that it grew into a symbol for him, one that for him represents nature, innocence and playfulness.

Happy Day, suggests a connection and completeness in the community formed by duck, flower, and people together, a contentment in being together.

In other paintings featuring the duck, there may be more physical separation between the duck and the person, but even then they remain in relationship with each other. They seem conscious of each other and sometimes the duck appears to be following the person; they interact as friends. Leunig has explained the recurring presence of the duck, and his work in general with the comment that, "I've learned to respect the whimsical."

Leunig criticizes the present mode of living for the artificial and harmful disconnection that often occurs. People, animals, plants were never meant to be disconnected; they are meant to be together in a cohesive ecological system. The painting, Pilgrim, and the prayer below it, both express that desire for a different way of living and being that is interactive, joyful, colorful, and loving. If we want that type of world, we must we willing to be pilgrims on a journey to slow down, listen, and be in a healthier relationship with the ecosystem we are part of.

Dear God,

We pray for another way of being:

another way of knowing.

Across the difficult terrain of our existence

we have attempted to build a highway

and in so doing have lost our footpath.

God lead us to our footpath:

Lead us there where in simplicity

we may move at the speed of natural creatures

and feel the earth's love beneath our feet.

Lead us there where step-by-step we may feel

the movement of creation in our hearts.

And lead us there where side-by-side

we may feel the embrace of the common soul.

Nothing can be loved at speed.

God lead us to the slow path; to the joyous insights

of the pilgrim; another way of knowing: another way of being.

Amen.

© by Michael Leunig

Reflection Questions: What relationships with non-human creatures are important to you? Have you found ways to slow down the pace of your life?

Louise

To see more of Michael Leunig's work, visit his website.