Sometimes a work of artistic redemption must go beyond the borders of our original vision to reach a point of greater completion.

Since my first visit to the Butchart Gardens in Victoria, BC, I have admired them both as an amazing work of art and as a parable for redemption.

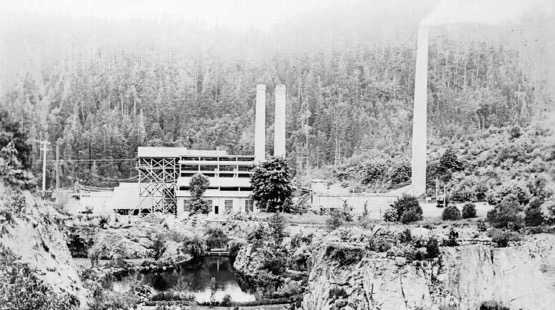

In 1904, Robert Butchart, owner of the Vancouver Portland Cement Company, learned of a large deposit of limestone, which is used to make cement, at Tod Inlet on Vancouver Island, and moved with his wife, Jennie and two daughters to establish a quarry and cement processing plant.

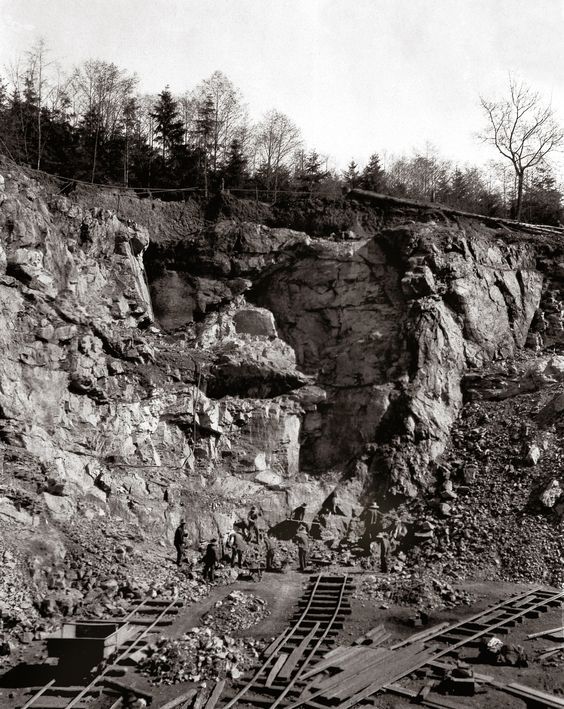

By 1912, the limestone deposits were depleted and the Butchart’s were left with a big hole in their backyard. Jennie Butchart envisioned transforming it into a beautiful garden.

She worked hard to make it happen, moving loads of topsoil by horse and cart, even hanging from a sling to push dirt and ivy into the crevices of the quarry wall.

After nine years of work, the quarry site became the Sunken Gardens. What was the bottom of the quarry is reached by a switchback staircase that leads 50 feet below to the garden floor, which is planted with beds of annuals, flowering trees, and shrubs up to the base of the quarry walls which are topped by Douglas firs, cedars and Lombardy poplars.

Jennie Butchart didn't just sit back and keep the beauty to herself. She shared it with friends, friends of friends, soldiers, people passing by. Its fame spread and by 1915, 18,000 people toured the garden, free of charge, with the garden open seven days a week. The gardens were expanded to add other gardens such as the Japanese Garden, the Rose Garden, and the Italian Garden.

When people suggested to Jennie that she should charge admission, she said, “The flowers are fleeting. Why shouldn’t people enjoy them? They’re free for all.” Only her private garden was off limits. The Butchart Gardens, passed down through the family, have continued to be expanded and, in 2004, what was once a depleted quarry mine was designated a National Historic Site of Canada.

Going Beyond the Borders

And so, it would seem that the work of redemption was complete, but it wasn't. The quarry wasn't the only area affected by the cement plant. The land and water surrounding the cement plant also suffered from the effects of the plant, but it would be nearly 100 years after the plant was closed before the clean-up work reached outside the frame of the Gardens.

SṈIDȻEȽ (pronounced sneed-kwith), or Tod Inlet, is the area’s WSÁNEĆ (Saanich First Nation) name and means “place of the blue grouse.” WSÁNEĆ peoples lived there until 1904, when, coming back from their summer harvesting grounds, they found their winter village replaced by the cement quarry and pier of Vancouver Portland Cement Company.

When the cement company opened, many came for work and after it closed and the workers left, cement foundations, discarded bricks, and a “garbage dump” from those who worked there remained scattered throughout the area. Non-native vegetation, construction debris and garbage were everywhere. The inlet water looked clear, but it hid an unhealthiness that was ignored for many, many years.

In 1995, SṈIDȻEȽ was acquired by BC Parks and named Gowlland Tod Provincial Park. Restoration of the land began soon after, with local volunteers removing invasive species such as Himalayan blackberry, English ivy and Daphne laurel and replanting the acreage with native species. At the inlet, community volunteers worked with a restoration group led by SeaChange Marine Conservation Society to restore both the land and water environments that were degraded during the cement factory’s operation.

The seepage from the former factory had contaminated both land and water, killing off most life. Toxin from sunken boats made the situation worse. The underwater debris, left from the cement factory, provided an ideal surface for jellyfish polyps to grow, eventually maturing into moon jellyfish. Although native, their overpopulation caused cascading problems in the ecosystem as they depleted the plankton, leading to fewer small fish, and fewer salmon. The ocean bottom was left with minimal biodiversity.

To restore the inlet, the ocean floor was mapped and divers removed what they could. Larger items, such as boat hulls, were lifted with a crane and barge.

Eelgrass shoots were planted in Tod Inlet to create water quality suitable for fish and other diverse kinds of life and to build habitat.

Concrete, contaminated soil, and abandoned bricks were hauled off the beach, which was then levelled to a slope and covered with gravel and sand, creating a soft shore to protect against rising sea levels and create marine life habitat. Heavily contaminated shoreline was excavated and replaced with clean sand and gravel to ‘cap’ the contaminated area, encouraging new growth of marine species and creating a safer area for human recreation. After three years, small clams, oysters, limpets and other marine life began returning. Eventually, crushed shells were added to the shore to further replenish sediment.

A Further Completion

The restoration of traditional guardianship is a third strand of this work. Throughout the restoration work, SeaChange and the W̱SÁNEĆ nation worked in cooperation and consultation. There has been a strong emphasis on honoring the land and its history, traditional food ecosystems of SṈIDȻEȽ, and a respect for the long connection of W̱SÁNEĆ people to this place. The work is informed by W̱SÁNEĆ elders and done with permission from the Tsartlip First Nation Lands Committee. W̱SÁNEĆ youth and other community members have labored together to do the physical work. After years of intensive restoration efforts with SeaChange, the SṈIDȻEȽ Resiliency Project has now shifted towards greater leadership from the W̱SÁNEĆ community by coming under the direction of the PEPÁḴEṈ HÁUTW̱ Foundation. Thus another important piece of the restoration is moving forward.

In this way, the original vision of restoration has broadened. The Butchart Gardens are a beautiful centerpiece of artistry that over a million people visit each year, but the work of artistic redemption has moved well beyond the borders of the gardens and is a deeper, richer work of art as a result.

Reflection Questions: How has the interconnectedness of nature surprised you? Is there an area of damage you hope to bring renewal to?

Louise

You can contact me directly at info@circlewood.online.