Baptized as a Catholic but long distanced from the Church, Henri Matisse, despite that distance, spent four years near the end of his life planning and creating all aspects, from roof to vestments, of a small chapel he considered the culmination of his work as an artist. As he said in a letter he sent upon its consecration:

This work has taken me four years of exclusive and diligent work, and it is the result of my entire working life. Despite all its imperfections I consider it to be my masterpiece.

Matisse came to take on the project through a bond of friendship with one of the Dominican Sisters for whom the Chapelle du Rosaire des Dominicaines de Vence, (or the Matisse or Rosary Chapel) was built. The story of their friendship and collaboration is a beautiful story in itself.

In 1941, Matisse was 71 years old and convalescing from a surgery. He needed a nurse and advertised for a night nurse who was "young and pretty." A nursing student named Monique Bourgeois responded. She propped up his pillows, read to him and took walks with him. It is said that her impish wit and straightforward conversation enchanted him. Although her nursing stint with him was short-term, their paths continued to cross and she became one of his models, a studio assistant, and a friend.

Shortly after nursing Matisse, Bourgeois contracted tuberculosis and went to a convalescent home run by Dominican nuns in Vence in the southeast part of France to recover. A couple of years later, she took her permanent vows there, becoming Sister Jacques-Marie. Matisse vehemently argued against her decision, but they reconciled and remained friends.

Matisse eventually bought a home at Vence, not far from the convent where the young nun was stationed. She visited him and told him of the plans the Dominicans had to convert a ramshackle garage used for prayer into a full-fledged chapel, hoping he might want to help with the project. Although he had never done anything like this before, he took on the project.

Matisse immersed himself in every aspect of the chapel, from the brushstroke sketches of a Stations of the Cross mural to the vestments and the altarpiece. He turned his vast flat into a studio displaying on all its walls his maquettes (sketches or models), most of which were life-sized.

Sister Jacques-Marie did preliminary design work and offered candid evaluations—and held the critics at bay. In the end, Matisse described the chapel as "their shared project."

The chapel, though very controversial at the time of its creation, due to Matisse's particular style and history, is, I believe, a portrayal of how the Church and Creation collaboratively infuse beauty into each other.

Matisse used just three colors in his stained-glass windows in the Chapel of the Rosary: pure blue, green, and yellow. Each of the three colors references an aspect of the natural world: yellow for the sun, green for vegetation, and blue for the nearby Mediterranean Sea, the Riviera sky, and the Madonna and together they fill the space with their vibrancy.

The chapel art takes elements of tradition (such as stained glass and the Stations of the Cross) and modernizes and simplifies them in a way that gives them a voice that resonates with a new time. There were many who, for various reasons, didn't want Matisse to work on the chapel. Some considered his work in the chapel blasphemous and/or ugly, but there were also people with standing in the church who were passionate about modern art and believed in its potential to have a positive effect on religious art.

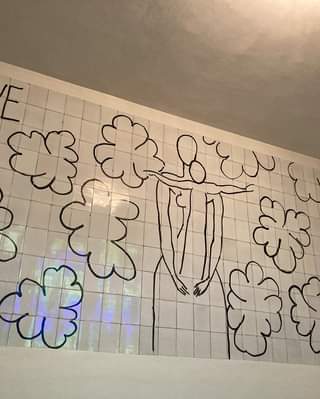

The Chapel of the Rosary, in the way that it translates old themes into a new language of art, shows this revitalization in action and the value it can hold. Compared to the complicated and ornate churches of the past with their gothic ornamentation and weighty traditions, this particular space feels light, airy, and alive—a place where color and joy interact and infuse the traditions of the church. This can be seen in the way that the colors of the stained-glass windows constantly bounce off the Madonna, the Stations of the Cross, and other saints painted in simple black lines on the white tiles of the chapel walls.

When you consider the much more elaborate and formal way these figures had been primarily presented in earlier religious art, you feel how differently these are being presented by Matisse.

Left: Madonna and Child by Giotti, Right: Ave Maria by Matisse

It makes me think about how tightly we cling to what we think is right and comfortable, afraid of losing what we know, but not seeing what we could gain by allowing new life to come into some of our old forms. Welcoming the stranger is a long-standing Christian value and perhaps that value has a wider application than we typically consider.

In welcoming what is strange and new, and being less protective of our traditions, we might not only be able to offer something worthwhile to the stranger, but most probably will be the recipients of new perspectives that can add color and life to our long-held traditions. As the Church encounters new art, new ways of thinking, and new questions that make it uncomfortable, I think the Chapel of the Rosary can be a reminder of the beautiful spaces that can be created as a result of welcoming and learning from what is strange to us.

Feel free to email me at info@circlewood.online or leave a comment below.

Louise