Today we welcome back Circlewood friend, Jeff Reed, as a guest writer for The Ecological Disciple. You can find Jeff's previous posts for our The Art of Creation column here and here. Today he takes an insightful look at landscape art.

I remember the sense of wonder I felt when first seeing Albert Bierstadt’s California Spring (1875) hanging in the DeYoung Museum in San Francisco eight years ago. So much so that I bought a print upon leaving. The large sky filled with dramatic clouds, the wide, spacious horizon radiating openness and freedom, the two majestic trees dominating the foreground in front of which peaceful cows forage in a wildflower meadow—this masterful arrangement sparked in me a feeling of the sublime, a sense of well-being, an unbridled affection for the natural world.

Representational landscape paintings have this power to evoke a chorus of positive emotion in me, and I, as a recipient of the influence of the western art tradition, am quite sure I am not alone in this, noting University of Arizona Museum of Art’s curator Lauren Rabb’s comment that the 19th century was the golden age of landscape painting in Europe and America.

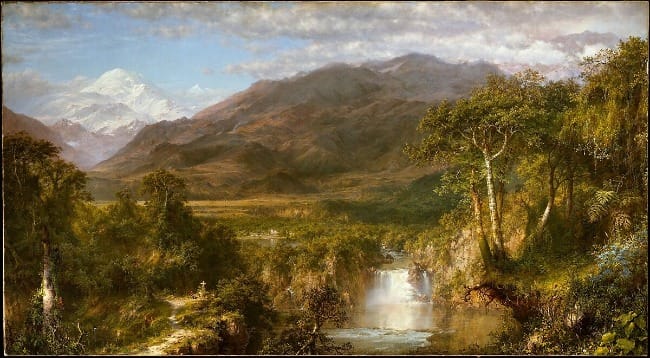

Take, for example, Frederic Edwin Church’s masterpiece The Heart of the Andes (1859). Influenced by art critic John Ruskin’s dictum that landscape painting should capture the natural world as realistically as possible without romanticizing the subject, Church’s photographic technique is indeed breathtaking. And yet, undeniably the realistic mastery creates a romantic response in the viewer: again, these feelings of wonder, awe, sublimity, delight, and affection.

I am a huge fan of this kind of art in the service of turning affections toward nature—as it has undoubtedly done for me. Yet, even as I applaud and celebrate the landscape genre, I realize that all good things have shadow sides. Just as wide-scene landscape art has the power to convert people into nature-lovers, at the very same time it has a tendency to inoculate these very same nature-lovers against the actual nature they are fooled into thinking they love. Enthusiastic fans of the natural landscape, as seen from the car window or roadside viewpoint, are often not interested in actually getting into that nature, with all of the brambles, boggy patches, detours, obstacles, not to mention the wild animals and hovering (or hidden) bugs.

Large-scale representations at a distance can create certain illusive and seductive images by virtue of hiding particularities. Distance sanitizes. Sometimes when flying into a large city like Los Angeles or Seattle, I am mesmerized by how neat and organized and clean the cities look from up in the air, when I know that if I were down on the corner block, amidst the noise and litter and obstructed views, my senses would offer up such a different assessment.

Landscape paintings hide many things: the heat and sweat of the sun in the sky, the sting of nettles alongside the dreamy stream, the labor of cutting a path through the thicket, the pungent smell of a dead deer in the crook of the decaying log, the buzz of the wasp cone, the haunting call of the coyotes in the middle of the romantic moonlit night. In addition to these unpleasantries of the real, wide-scene paintings can also mask history with its real narratives–for example, overlooking the presence of Indigenous peoples within the sphere of the landscape view, allowing us to interpose our own narrative fictions on top of the true story of the particular land-scene we are easily gazing at. As Alan C. Braddock, Associate Professor of Art History and American Studies at the College of William and Mary, writes, "Romanticism helped institutionalize the wilderness aesthetic (a.k.a. landscape art) which has done damage to our understanding of history by erasing the knowledge about the historical presence of Indigenous peoples.” In these ways, then, we are often released from having to grapple with bothersome details as we are given an aesthetic bath that costs us little.

When I think about the potential sanitizing lure of landscape art, I think of a poem by Canadian poet Robert Bringhurst entitled These Poems, She Said. The poem’s speaker is the wife or lover of a poet, critiquing the poet’s inauthenticity, who is more committed to the artistic craft than the thing the art is attempting to represent. Some excerpts:

These poems, these poems,

These poems, she said, are poems

With no love in them…

These poems are as heartless as birdsong, as unmeant

As elm leaves, which if they love love only

The wide blue sky and the air and the idea

Of elm leaves…

Love means love of the thing sung, not of the song or the singing.

While I genuinely admire 19th century landscape art and its ability to create a true doorway into an affection for nature, I also suspect that such affection is vulnerable to stopping short of forming a true love for nature as long as the viewer stays content to remain apart from the subject. Unless landscape art succeeds at compelling people into nature itself, it very well may create a love for the song or the singing, but not for the thing sung!

There is an interesting exception to the phenomenon of landscape art as an inoculation against the realities of nature in Thomas Cole’s famous The Oxbow (1836). Cole uses the landscape genre to intentionally raise awareness of the problematic American spirit of aggressive and consumptive westward expansion which was quickly devouring the land in the nineteenth century rush toward frontier dreams, fueled by the philosophy of Manifest Destiny. His painting deliberately contrasts the wild undeveloped country beside the settled and cultivated country in an attempt to shock the reader into experiencing what was then being lost in the greedy demand for agricultural land and civilized space.

The Oxbow functions with anti-sublime sublimity. The initial feeling upon encountering the painting is the usual sense of delight in the wide space, the pleasing color palette, the dramatic clouds, the expert technique. But upon reflection and further examination, a bee gets in the viewer’s bonnet. Something begins to bother. The dark clouds in the upper left corner seed a subtle ominous sensation. The leaning tree in the foreground looks sickly and teetering. The pale colors of the settled lowlands grow unappealing against the lush green of the wilderness. The viewer, instead of being lulled into a romantic notion of nature’s beauty, is being confronted with the cost of expansive progress, a tension that will require the viewer to make a decision whether to ignore the budding awareness or to let the awareness take root and begin to grow.

Cole’s Oxbow reveals an important facet of art’s powerful functionality: to goad us to consider something further. It is my hope that the best and most breathtaking landscape paintings will, instead of inoculating us, spark in us both the desire and the intention to know such scenes first-hand, from within, in company with all the other senses of sight, sound, smell, and touch. May the work of Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Edwin Church, Thomas Cole, and others call forth new hikers and gardeners, trailblazers and homesteaders. May such landscape art not only engender affection for the idea of nature, but power our resolve to care for it in light of the modern day crisis of climate change which is actually threatening the very beauty that these artists captured. May we love the thing painted more than simply the painting of the thing.

Reflection Question: Consider your own love of nature. How would you rate it on a scale of 1 to 10, 10 being fervent and 1 being tepid? Is your love for nature more a love for the idea of nature or for the actual natural world that you have experienced first-hand? How might you deepen your actual love for nature this week?

I welcome your comments below, or email me directly at windinthereedspub@gmail.com.

Jeff