Tanabe Chikuunsai IV's most well-known works catch one's attention. For one commissioned project at the Asian Art Museum, the artist and three apprentices from his studio in Japan spent two weeks weaving strips of bamboo into a complex, twisting shape that reached to the gallery ceiling.

His sculptures, however, are not stand-alone tributes to one person's creativity and skill. They are rooted deeply in tradition, community, and the earth itself.

Bamboo artistry is a long and respected craft in Japan, stretching back at least 1,000 years, and Chikuunsai's family has been part of this tradition for over 120 years which is when his great-grandfather, Chikuunsai I, first took up the work of bamboo art.

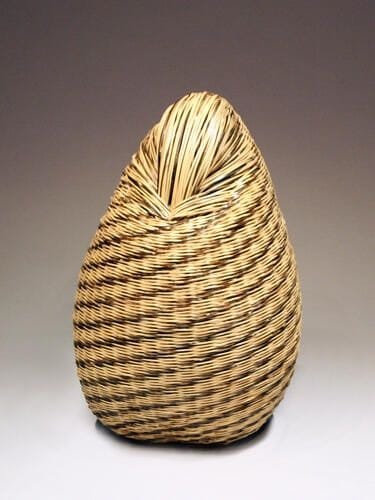

List of pictured works: Round-handled Flower Basket, Chikuunsai I; Senshū-ami Weave Flower Basket, Chikuunsai II; Delight for the Future, 2009, Chikuunsai III; Disappear II, 2019, Chikuunsai IV; Heaven/Wind, 2014, Chikuunsai IV; Connection-Birth, Chikuunsai IV.

Each generation has learned from the prior generation and then added something of their own into the mix, from Chikuunsai I, who made densely woven basketry to Chikuunsai II, known for using strips of bamboo less than a millimeter wide, to Chikuunsai III who built complex unwoven abstract forms of unsplit bamboo. Chikuunsai IV incorporates all of these into his work, adding the innovation of large-scale architecture and room-sized art pieces to his smaller, more traditional work. Other family members, including Chikuunsai IV's mother and uncle have also been bamboo artists.

Chikuunsai IV's name itself is rooted in tradition. First given the birth name of Tadao Tanabe, he was later dubbed Shouchiku or "little bamboo" as a junior artist who was progressing in the skill. Later, when his father died in 2014, he was skilled enough to inherit the name Chikuunsai, or "Bamboo Cloud Master," with the IV attached to indicate the number of his generation.

He cares deeply about the traditions of bamboo art and works to pass them along to his children as they were passed on to him. He works with apprentices as well, teaching them the traditions he has learned. As he says, the master/apprentice bond is deep, and goes beyond the work, sharing life together as he passes along techniques and perspectives that have been passed down three generations (and more considering that his great-grandfather himself was mentored) to reach him. When they work on a project together, they "share the same way of thinking and create the work together." His work with the bamboo and his apprentices is imbued with spiritual meaning.

He is deeply respectful of the bamboo he uses in his work. His bamboo of choice is tiger bamboo (torachiku), which grows only in the mountainous areas of Kochi, Japan. Unfortunately, this type of bamboo is increasingly rare as are those who take care of the bamboo.

As he says, "the soil has been affected by environmental pollution and global warming, showing detrimental results in the beautiful outer layer of tiger bamboo." Once 100 families tended the bamboo grove, but only three people remain – a decline in the trade that Chikuunsai IV wants to reverse while raising awareness of nature’s fragility. "My hope is to preserve such beauty for future generations," he adds.

His stated goals for his work are to give people an understanding of the importance of ancient craftsmanship, a respect for nature, and a renewed sense of responsibility for the world they are giving to the next generation—including bamboo forests, or chikurin.

For his site-specific installations, Chikuunsai started adding bamboo types besides tiger bamboo including: madake (giant bamboo), kurochiku (black bamboo), susudake (smoked bamboo), and kikkō-chiku (“tortoise shell bamboo”).

Chikuunsai IV’s begins work on his installations by selecting the stalks he wants to use. Then, he cuts and splits them into strips, moistens each strip with water so that it is bendable, and plaits it into the installations. He twines the strips together using weaves such as the turtle shell weave, which has a hexagonal or honeycomb structure. Using no adhesives, he relies on the strength of the bamboo to keep his installations erect and intact.

His respect for his material includes reusing it.

“At the university, I noticed that making art produced a lot of waste, and that making art was almost like a selfish act,” he said. “I love bamboo so much, I want to take care of it and use it as long as I can.”

“It’s not like ceramics. I can make something and take it apart and remake it." As he takes down one work, he cleans the bamboo strips so that he can use them again. When he produces a work, about 10% of the bamboo deteriorates or breaks, so he adds new pieces as is needed.

“By reusing the material, I wanted to express nature’s cycle of birth, that we are co-existing with nature,” explains Chikuunsai. “Bamboo strips unraveled by Americans will be used to make a work in the next country, which is then unraveled by people in that country. Being able to make these kinds of connections is also part of the appeal of this installation.” He has reused the same bamboo in as many ten different installations.

He started creating his room-filling pieces to appeal to a more general audience. As he has said, “I began to realize that making large works appeals to young children. People are inspired. In Brazil, some people cried. There was an exhibit in Paris that was up for a year, and I saw people sitting inside the gallery, looking contemplative and sort of relaxed, almost like a healing experience.”

Regarding his exhibit called Connection, he said, “Part of the title Connection is connecting generations of family to the future. I’m using the bamboo as a metaphor for connection from one cycle of life to the next cycle of life.”

Whether the works are big or small, he says he listens to his instincts. “I’m almost like a conductor with the large installations, trying to bring everything together, “ he said. “With a smaller piece it’s more like a solo performance.”

Reflection Questions: In your work, faith, and family, are there traditions that help you connect to your human community and to the earth? Are there innovations that you can bring to those traditions that both honor the traditions and also bring creativity and greater sustainability to them?

Feel free to comment below or contact me directly at info@circlewood.online.

Louise

To watch a stop-motion video of Chikuunsai IV and his apprentices constructing an installation, watch the YouTube video below.