Some art seems universal and could be made anywhere, but some art is rooted so specifically in a particular place that it does not seem that it could have been made anywhere else.

Tree Bark into Cloth

When Polynesians migrated by canoe to the Hawaiian Islands around 300-600 AD, one of the few plants they brought with them was the wauke, or paper mulberry. Its bark was used commonly throughout the Pacific for cloth, but the Hawaiians developed three unique innovations that made their fabric especially fine. These included a fermentation process which created a soft, luxuriant material, the creation of distinctive watermarks on the cloth, and the use of bold natural pigments. These three together created uniquely beautiful fabric.

Captain James Cook commented in 1778, "One would suppose that they (Hawaiians) had borrowed their patterns from some mercer's shop in which the most elegant productions of China and Europe are collected, besides (having) some patterns of their own.... The regularity of the figures and stripes is truly surprising."

Kapa (Hawaiian bark cloth) was made from strips of inner bark of trees which was soaked and then pounded with a wooden beater until the fiber became very thin. Kapa beaters had four sides with grooves of different coarseness. The coarsest side was used to break down the wet bark first, then the two sides with finer grooves were used, and then the smooth side of the beater was used for the finishing touches. This created an especially soft fabric.

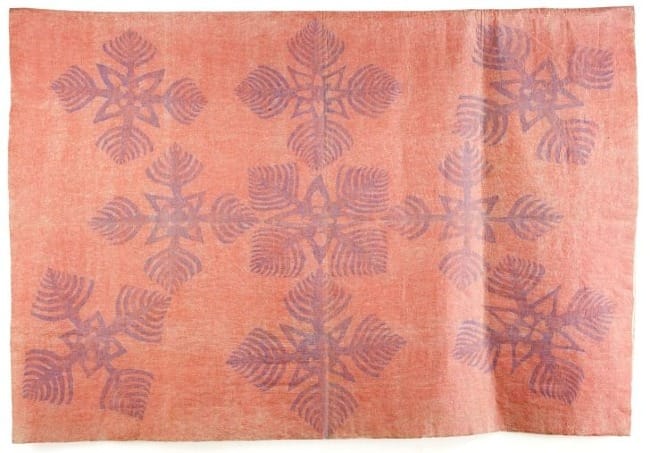

The strips were then felted together (felting is agitating and compressing textiles until fibers catch and weave together into a single piece of fabric). After the beating and before the kapa is dried in the sun, makers would emboss their particular design on the cloth so that it would show through like a watermark on stationery. After being bleached in the sun, it was exposed to night dew and then repeatedly bleached again, creating a sheen with some moisture-resistance.

Ancient Hawaiians would wear the kapa as clothing—wrapping newborns in it, clothing warriors and dancers, and wrapping their dead in it. It was also used as bedcovers, called “kapa moe.” One of the clever things about this bedding is that it had several layers of cloth, but they were only connected at one end, so that the number of layers used could be adjusted according to the season and temperature. The bottom sheets were undyed; only the top sheet was dyed and stamped with a design. Often fragrances from Hawaiian flowers were added. For the Hawaiians who made it, kapa held spiritual significance, holding the mana (life force) of the plants it was made from and those who made and wore it.

Innovating Traditions

When missionaries came from New England, bringing woven cloth and their own quilt-making traditions, kapa-making disappeared. In fact, as one Hawaiian historian regretfully noted in 1870, “All are dead who knew how to make coverings and loincloths and skirts and adornments and all that made the wearers look dignified and proud and distinguished.” - Samuel Kamakau.

Cotton did not grow in Hawaii, so the fabric was imported, alongside the traditions of needlework and patchwork quilting made from fabric scraps. However, the Hawaiians did not take on the new practices wholesale, but, as they had with kapa cloth, added their own innovations. Without saved fabric scraps to draw from, cutting up pieces of cloth just to sew them back together made less sense. So, they developed their own style, folding and cutting the fabric as paper snowflakes are folded and cut, creating a central motif radiating outward from the center with each side a near-perfect mirror of the other. Traditional designs are based on Hawaiian flowers and plants, including first and foremost the breadfruit.

Stories say that this quilt technique was created when some Hawaiian women laid fabric on the grass to dry and noticed the leafy shadow cast upon it from the branches of the breadfruit tree overhead. A Hawaiian woman went to the fabric and cut out the pattern, then laid it onto another fabric and stitched it, and the first Hawaiian quilt, an appliqué quilt instead of patchwork, was created. From that breakthrough more designs were quickly invented, based largely on commonly found Hawaiian plants and flowers. Like the kapa moe, this kind of quilt has several layers that are connected on one side and unstitched on the others.

Rooted in Tradition, Rooted in Place

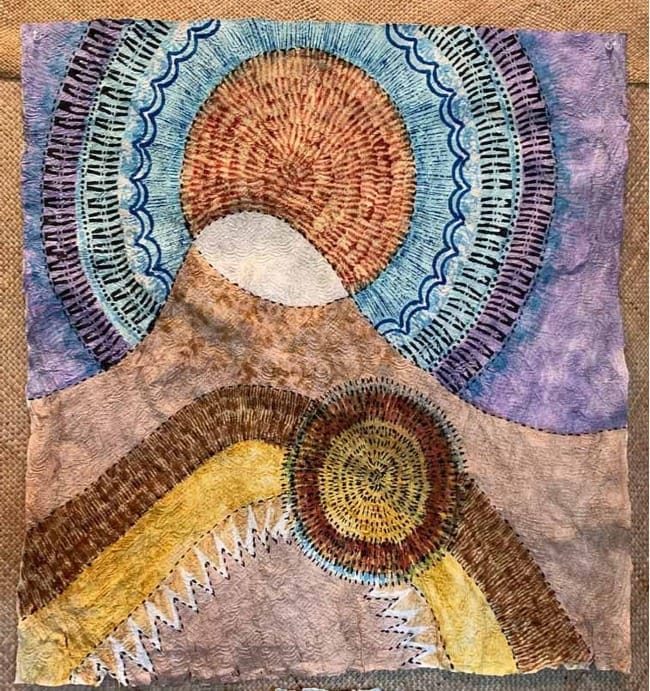

During the Hawaiian cultural renaissance of the 1970's, a few Hawaiians wanted to bring back the lost skill of the traditional and neglected kapa, but the hands-on knowledge had completely disappeared, so those would-be kapa artisans had to figure out each step of the process on their own, using clues from traditional songs, newspapers, and from museum samples to piece it together. Looking at old kapa quilts and gleaning what knowledge they could from the writings, they slowly found how to create the traditional vivid colors, delicate barkcloth, and the other skills and secrets which had been lost for more than a century.

Through their dedication, the art form was eventually regained and both traditional and contemporary versions of the ancient art form spread. Interest has expanded now so that there are exhibits celebrating its artistry and, in spite of the immense labor and time required, interest continues to grow.

Currently, an exhibit titled “Kuku Kapa E” is on display in Waimea. It is curated by the daughter (Roen Hufford) of one of the people who brought back the art of kapa (Marie McDonald). The daughter herself is a kapa artist, having learned the skill from her mother, restarting the passing down of such knowledge from one generation to another.

This use of the tradition, both traditional skills and traditional flora, suggests an art that is deeply rooted in place. This is a place-based art, specific to that particular place. With both types of Hawaiian quilt, Hawaiians began with what came from somewhere else and adapted it to be congruent with their place and artistic bent and created something very Hawaiian in the process.

It makes me consider the difference between place-based art and rootless art, and what is unique about art that comes out of and digs itself into a particular place. By both learning and passing on such traditions, Hawaiian quilt artists celebrate the history of these particular islands in a way that leaves room for new ideas and new perspectives and also guards against losing another time the knowledge it required so much work to regain.

To leave a comment, click in the comment box below, or email me at info@circlewood.online

Louise

It's not too late! If you have found ways that art helps you forge deeper connections with the creation within and around you, send in a picture or example to me by Monday so I can include it in next week's post.