Wayne Valliere, whose native name is Mino-Giizhig ("Good Sky"), is an Ojibwe artisan skilled in many areas of native art, including beading, quillwork, drum making, painting, carving, basketry, crafting hunting tools, traps, lodges, and cradleboards; he is also a gifted singer and storyteller. His involvement in birchbark canoe making has been particularly significant as this craft, central to generations of Ojibwes, has faded away. Valliere can name only six native people who hold this skill and knowledge among the Anishinaabeg people of the Great Lakes region; one of the other six is his elder brother, Leon. Through his work as a birchbark canoe maker and mentor to others, Valliere ties together past, present, and future, joining water and land, new generations and old traditions.

Mentoring Others

For Valliere, the significance of what he does goes beyond just creating a canoe. It is about the generations which have come before, the generations which follow him, and the importance of canoe making with each. He first started learning about canoe building when he was 14 and made his first one when he was 16.

“Our birchbark is so important because it signifies our identity,” Valliere said. “It’s our connection to our past. It’s very important that we don’t lose this craft because it connects us to our grandmother, the Earth.”

He is devoted to passing on the learning to others, particularly younger generations, and does this in one-on-one mentoring relationships such as he himself experienced when he was learning, and in various classrooms. His classrooms include the public school at the Lac du Flambeau Reservation in northern Wisconsin and universities such as the University of Wisconsin and Northwestern University.

As he sees it, "The knowledge does not belong to me. It belongs to my community. And it’s my job to keep our culture alive. That’s why I do the work I do."

The Craft

The knowledge and skill involved in birchbark canoe making encompasses a large skillset and large bodies of knowledge, beginning with the harvesting of the wood that is used.

Canoe builders harvest giizhik (white cedar), wiigwaas (birch), waatabiig (spruce roots), and bigiw (pine pitch) from wetlands, woodlands, lakes, and swamps— a physical and spiritual reminder of their ties to the Earth, or "Grandmother's Back," to use the Ojibwe expression.

Valliere says, "We harvest from our grandmother’s back. We ask permission for the birch tree, for the bark; we beg it a thousand pardons before we harvest it. The cedar tree, for our woodwork, we beg it a thousand pardons before we take it. We have a ceremony: We [use] tobacco and we make an offering, because we don’t just take, we give back, and we always leave something to seed.”

This perspective and practice has its roots in the traditional origin story of the Ojibwe. Hundreds of years ago, while living on the East Coast, the people who would become the Council of Three Fires, of which the Ojibwe are one, received a prophecy that they would be destroyed unless they moved west to “the place where food grows on water." The people obeyed the prophecy, traveling to Wisconsin, Ontario, Michigan, and Illinois (including the Chicago area) — and there found wild rice growing on water.

The birchbark canoes, useful for gathering rice, sliced smoothly through water, were stable enough for spearfishing and carrying moose after a hunt, and helped them survive. They were light enough to carry over land and were more maneuverable than canoes from solid wood, which gave them an edge in battles.

“Birchbark is a great gift that was given to our tribe a long time ago; It was going to be a protector of our people and would serve us in a great way.”

The craft of birchbark canoe making is complex, and it takes years to learn how to build one independently. Tradition is that any canoe builder must build at least four canoes under a mentor who is a master builder before they can build their own canoe.

A few steps in the process are shown above: the brace for the canoe is built, bark is cut down to the correct size, the bark is sewn onto the frame, the frame is lashed with spruce roots, the bottom of the canoe is covered, the ribs are cut, bent, and inserted, the gunwhale is lashed, pitch tar is applied over the sewn seams.

Making a birchback canoe involves long and detailed steps and stages which must be followed in particular ways for the canoe making to be successful. Even before the actual construction begins, the wood must be properly soaked so that it will bend without breaking. Slots must be carved so that pieces fit together snugly. When it comes to the sewing, stitches must be tight and durable and must be done carefully so that the stitching doesn't tear through the bark. The pine pitch must be prepared and applied correctly so that it thoroughly covers the stitches and prevents leakage.

Inherent Meaning

Traditionally, Ojibwe canoe building was a communal or family event, with many hands of all ages joining in. In Valliere's work with classes and other groups, this has also been the case, with people from beyond class rosters helping and learning about the craft and traditions.

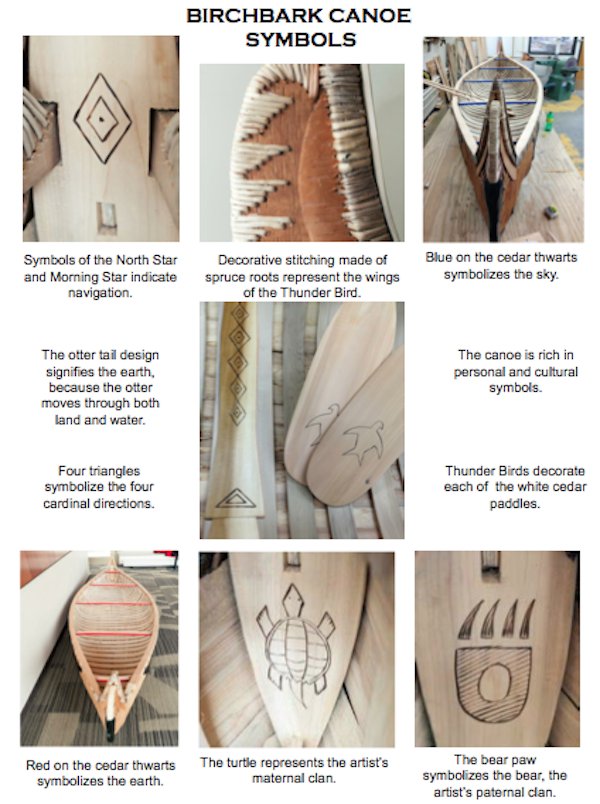

Symbols which respect and acknowledge both the canoe maker's family history and the larger Obijwe community are incorporated into the structure of the canoe. The image below shows the meanings of the traditional images and colors used in a canoe built by Valliere.

For a people who have always identified their life strongly with the water, canoes recall and reinforce this connection. The traditional knowledge of the ecosystem which the people are and have been a part of, is taught not just with words but with the practice and work of their hands. Through the craft of canoe making, the builder acquires a whole host of knowledge having to do with forest ecosystems, water ecosystems, weather, fish cycles, plant growth as well as an attitude of respect and understanding of connection and responsibility.

This learning is not separate from spiritual meanings and significance. As Valliere says, “This is the ancient land of our fathers, of our ancestors, who came into this land and had ceremonies in this land, raised their families in this land. We are descended of those people, and to us, it’s like coming back home. The spirits who live on this lake, they know who we are. We’re not strangers here. Not to the spirits that live here.”

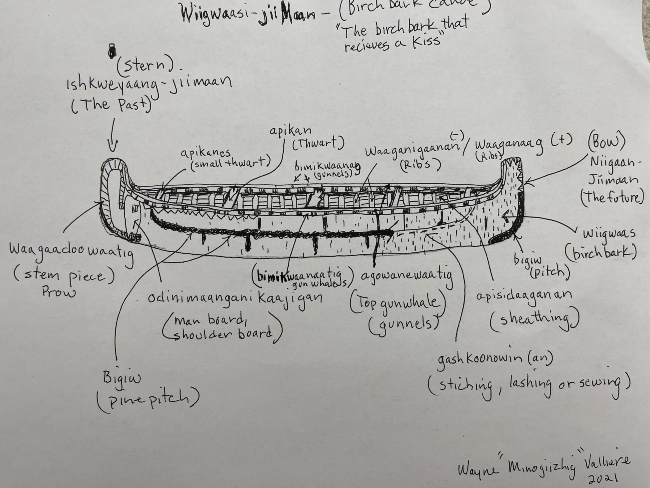

The drawing above shows how a worldview is reflected in canoe making. In the Ojibwe language, for example, the words for the bow and stern of a canoe—niigaan jiimaan and ishkweyaan jiimaan—also refer to the concepts of the future and the past; one’s passage through life is seen as a journey by canoe. The future (the bow) and the past (the stern) are constant reminders of the continuity of life, history, and people. They represent a way of perceiving the world for Anishinaabe people.

For Valliere, what he does and teaches is a significant part of a purposeful life. "I was born with a white streak in my hair and my grandmother told my mom I was a reincarnated Elder and I would carry the torch forward," he said. "I've done my best to do that. When I see young people get on the right path with culture, it's very gratifying. I feel like my life's work has meant something."

Reflection Questions: Are there significant crafts and traditions in your family or culture that remind you of your tie to the past, the future, and your connection to the earth? Are there crafts and traditions you can either pass on to another generation or learn from an older generation? What experience do you have of learning through practice rather than strictly through ideas and books?

Feel free to comment below or contact me directly at info@circlewood.online.

Louise