This is the first in a series of two articles in which I explore the work of Makoto Fujimura. In this article I explore his work in the Nihonga tradition.

The art of Makoto Fujimura takes time—both time to make and time to fully experience. As an advocate and practitioner of “slow art,” Fujimura believes that creating art and apprehending it as a receiver are slow processes—that art is not a fast food meal that can be swallowed in one quick bite, but is a feast to be lingered over, savored, and treated with respect and attention.

What is true of Fujimura's paintings is also true of his writing on the subject, for both are best mulled over and revisited more than once.

The Art of the Slow

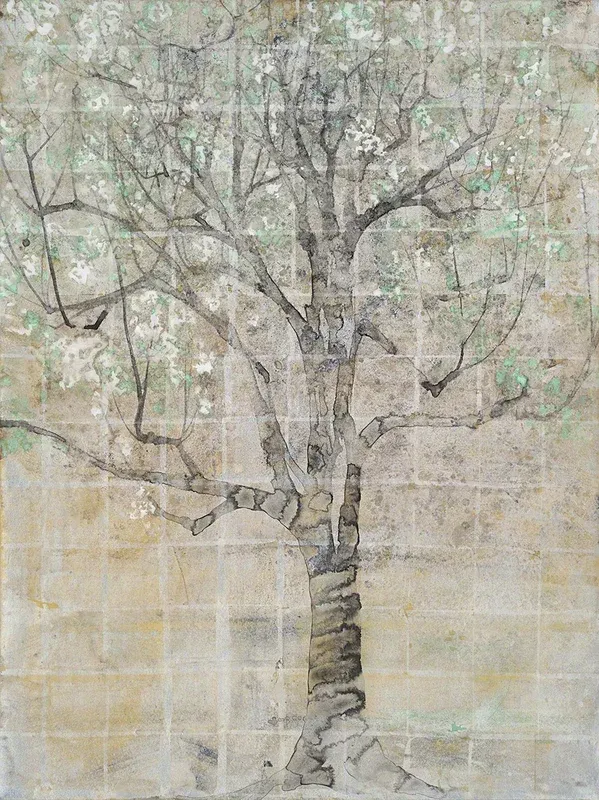

In his paintings, Fujimura works within the Nihonga tradition, a painting style that has been developing in Japan since around 1900. The processes used in Nihonga require time, patience, and particular materials. Fujimura spent seven years in Japan learning from a master in the tradition.

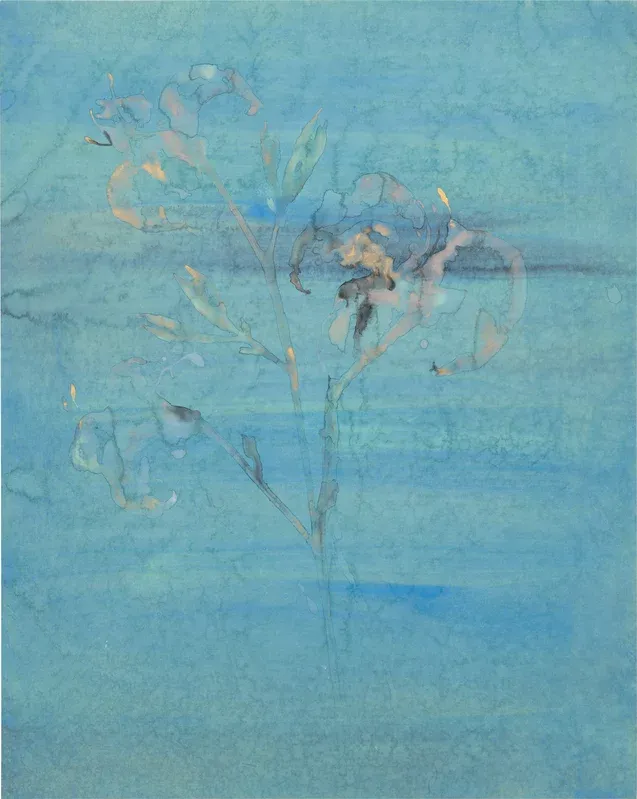

The pigments are made from various pulverized materials such as seashells, minerals, and precious metals including platinum and gold. The pigment layers are painted onto paper, oil, wood, or plaster using an adhesive of animal glue. Many layers are applied—for example, there are 60 layers of pigments in the painting pictured above, Consider the Lilies. In Fujimura’s words, this art form is “a slow process that fights against efficiency.”

Along with the slow process of creation, Fujimura advocates for a slow process of comprehension as well, suggesting that a viewer should spend at least 10-12 minutes in front of a painting, absorbing and adjusting, and letting themselves be immersed within it. This will lead to seeing things that cannot be seen with a single short glance.

The difference in colors become more evident; the layers become more distinct and subtleties of the painting become visible. In Nihonga, the grainy minerals particles refract light and color on their surfaces and this can only be seen and fully experienced through long and careful observation.

This slow approach to creation and apprehension of art aligns with the artist’s philosophy of art. He argues forcefully against the efficiency that has become so much a part of Western thought, even in art. He believes that efficiency makes real creativity impossible and is in direct contradiction to the creative nature of God, which, as a Christian, is foundational to his own theory of creativity.

“The Theology of Making assumes that God created out of abundance and exuberance, and the universe (and we) exist because God loves to create” (from Art + Faith: A Theology of Making, by Makoto Fujimura).

An Ecosystem of Tradition

As he describes in his book Art + Faith: A Theology of Making, it is not just an individual's painting techniques that creates a work of Nihonga, but an entire supporting community.

Nihonga...involves an ecosystem of trained craft folks of multiple generations, from paper makers to brush artisans, and that ecosystem is built on trust and relationships... People assume that Nihonga is about the materials and tools—that we can learn it by taking lessons and sharing recipes. But a recipe or a formula alone cannot make art. I have come to believe that Nihonga is part of the historical ecosystem of care and nurture of culture that the Japanese have cultivated for more than a thousand years, an integrated way of making that affirms the beauty of nature. Nihonga is impossible to teach outside of that ecosystem… (from Art + Faith: A Theology of Making, Makoto Fujimura).

To think of an art form in terms of the community that makes it possible changes it from a purely individual act of creation to one that is partially created by all those who contribute in different ways to its formation. This includes those who had a part in the development of its form to those who make the material and tools used within the art.

Contemplation and prayer are intertwined with Fujimura's work, and his art is a fundamental expression and practice of his Christian faith. He views "making" as central to what the Church is called to be and do. We are invited by God to be co-creators with God in bringing about the New Creation.

“God’s design in Eden, even before the Fall,” he writes, “was to sing Creation into being and invite God’s creatures to sing with God, to co-create into the Creation.”

In Fujimura's thinking, art (and the Church) should seek to care for the culture, to steward and tend it, striving for its flourishing, rather than battling it as you would an enemy. He founded the International Arts Movement, a "movement of restoration—of thoughtful creation and stewardship, where we all work together to renew the beauty of the world around and within us," believing this work of restoration to be work that people of many types can participate in.

"The body of Christ provides the Christian ecosystem for teaching the New Creation, and this can happen if the church once again becomes a place of making, the heart of beauty in the world, and a witness to mercy. As hard as it is to do a workshop representing a millennium of wisdom and the ecosystem of Nihonga, it is harder to communicate the gospel in the fullest self."

Reflection Questions: Are there times and ways in which a mindset of efficiency makes your experience less rich and deep? Does the idea of co-creating with God energize you? Excite you? Worry you?

See more work from Makoto Fujimura and find more about the paintings pictured in this article by visiting his website. Find his writing here and link to a video in which he talks about his art and faith just below. And be sure to check back next week for part two.

Feel free to leave a comment below or contact me directly at louise.conner@circlewood.online.

Louise

Want to learn more?

Find out more or support our parent organization by clicking below.