When you lie down a field of flowers, the sights, sounds, and smell surround you—you are immersed in the experience. How do you replicate that for people within a gallery space? For Rebecca Louise Law, an installation artist who lives in Snowdonia, Wales, creating immersive experiences of nature has meant bringing massive amounts of flora inside to where the people are.

Garten, Bikini Berlin, Germany

Immersion

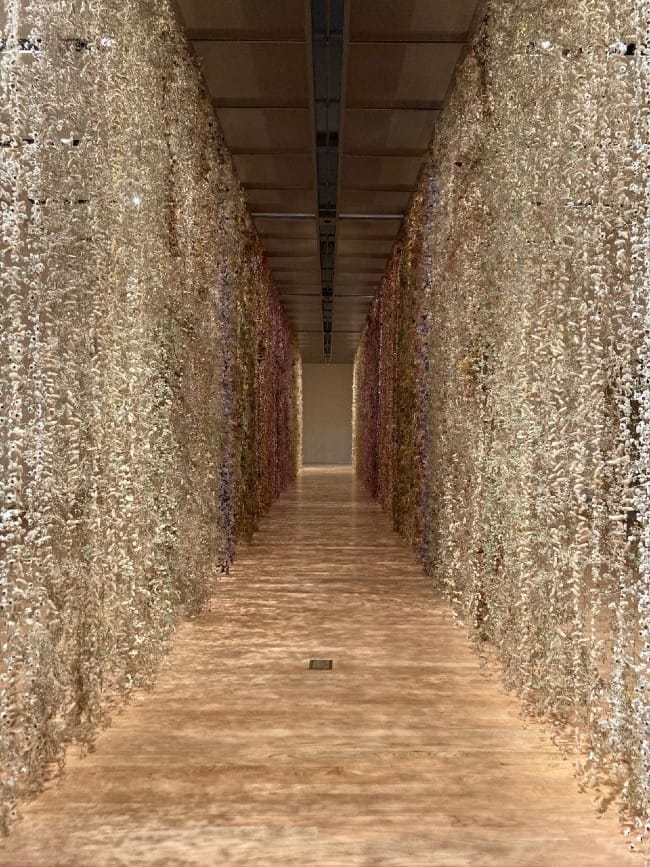

Law's installations, especially her largest scale ones, aim for complete immersion. To do this, she turns public spaces basically into flower gardens. Trained as a painter, but having turned to flowers as her choice of medium, she now "paints in the air" by threading thousands and thousands of flower parts onto wires that are hung from the ceilings of galleries and other spaces, creating three-dimensional curtains of blossoms in various stages of development.

Born into a family containing several generations of renowned gardeners and artists, she has deep-rooted experiences of the natural world that are filled with awe, delight—and flowers.

“As a child, we had acres and acres to run free through the wildflowers, forests, and streams. I suppose I always wanted other people to get a part of that freedom in nature.” [1]

Takeaways

For Law, this immersion is intended to do more than send the viewer away with a transitory experience of beauty. She hopes those who enter her art come away with a transformed view of their own connection to nature, as a human part of nature.

I love challenging the relationship between humans and nature. My work is site specific; I work to the maximum capacity of the space and consume it with nature. By bringing the outside in, I change the perspective — and invite the viewer to interact and respond to the new space. [2]

Law communicates this connection through the immersive experience, and the identification of commonality she curates in such works as her current exhibition, called The Journey, an installation in the Cummer Museum in Jacksonville, Florida. It is a grand-scale installation which required over one million previously cut and preserved botanicals to be connected by hand using copper wire and hung in floor to ceiling strands nearly 18-feet high. These strands create two walls of flowers that the viewer walks between, thus creating the experience of a journey being taken.

We are interconnected with nature; it is vital to understand that it is not separate as we have been brought up to believe. [3]

This particular journey is a journey through nature's cycles and rhythms. Full of scents and sights, it is meant to parallel a life's journey in which we are always moving and changing within the wider natural world, which is also constantly moving and changing.

She introduces the exhibit with these words:

Our Journey together with nature is fragile.

Living is a gift.

Time is a gift.

Anxiety is real.

Sickness is real.

It is time to heal.

Both nature and ourselves.

Time to be a community.

To heal together.

Take away the mirror.

Put down the phone.

It’s time to be present.

How she frames that experience with her art is through using the flowers, preserved in various stages, including the stage of decay, to parallel a human journey through life. All parts from the beginning (the formation of a cell) to the end (decay), are beautiful to Law; she sees the cyclical aspect of nature as central to its character, and central to us as human parts of nature.

Sustainability

Her respect for the components of nature is reflected in her artistic habits. She takes seriously the cost of waste and commercialism, incorporating that concern into her work. First of all, she uses flowers grown locally when outside of Britain, and, when in Britain, uses flowers she grows herself at her own home garden in Snowdonia and flowers from another small family-owned business in Normandy.

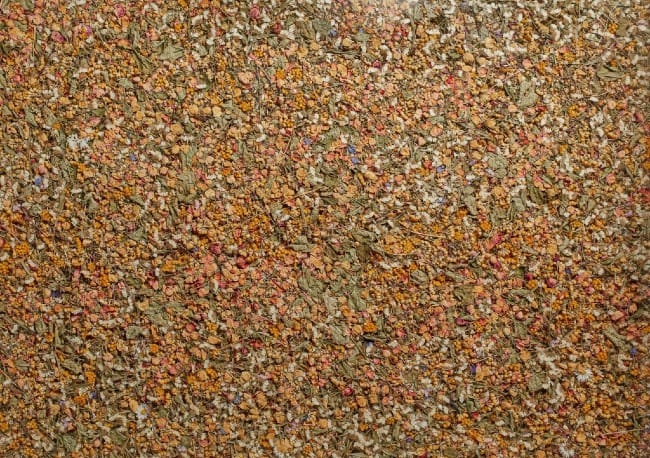

Secondly, she doesn't merely discard the used flowers from her exhibits. In fact, her time working in a florist shop, watching leftover flowers routinely discarded as valueless, made such a deep impression on her that she has found a different way to handle the flowers left from her work.

Once an exhibit is over, she carefully boxes up and saves everything from the exhibit, preserving and storing the flower pieces in climate-controlled spaces. She will reuse these pieces for future exhibits, or recycle them if reuse is impossible. In a recent count, she had over 1,200,000 million dried flowers stored in different parts of the world.[4]

Dead flowers aren't waste to her. Every part of the life cycle is beautiful and useful to her, even the dust.

The flowers I preserve, take time to preserve, and I treasure every one of them. Even when they eventually turn to dust, too small to sculpt, I collect them and contain them within glass. I have always treasured every flower that has been entrusted to me...Once you put time into cultivation, you start to value the gift of a single flower. [5]

Community

Another aspect of her work that is important to her is how it can create community. Many of her exhibits require hours and hours of labor and have become opportunities to bring the community together in common work as people gather to do the necessary work. For example, her installation, "Community" used 520,000 plant elements, which all had to be bound together with copper wire. Nineteen local organization were involved in preparing the exhibit, with 1650 volunteer hours donated by the people in the community. Installation of the exhibit took 17 days to complete.

The result of this community effort is an ownership of the project by the community that makes it happen. It becomes more than just something that is brought to the community, it becomes something that the community helps bring to itself.

She has created many community based exhibitions, including Forilegium (Italy), The Womb (U.S.), Captured (Germany), Banquet (France), La Jardin Preserve (France), Pride (Denmark), Cherry Blossoms (England), Cotton Fields (England), and Outside: In (U.S). Each of these projects in which volunteers were used has created a sense of community and shared purpose that has made the installation more meaningful.

Click below to walk through one of her exhibits and hear her speak about her work.

To see more of Rebecca Louise Law's work, visit her website.

Reflection Questions: If you could bring an experience of nature to other people, what would it be? Are there things you treat as waste products that might be reused? Are there things that others throw away that you have found uses for?

Have comments or questions? Comment below or directly to me at info@circlewood.online.

Louise

[1] Miller, A. (2014). Flower Magazine, retrieved from https://flowermag.com/

[2] Jakeway, A. (March 26, 2015). The Mad Botanist, retrieved from https://www.we-heart.com.

[3] Burgos, M. (June 3, 2021). Lampoon Magazine, retrieved from https://lampoonmagazine.com/blog/

[4] Graham, L. (October 1, 2020). Elysian Magazine, retrieved from https://readelysian.com/

[5] Vogel, M. (August 27, 2020). Art Net News. retrieved from https://news.artnet.com/art-world/