English stained glass artist Thomas Denny has completed about 60 commissions primarily, though not exclusively, in English churches; each one of those is rooted in the particular commission, community, and place of their inception. On a basic level, stained glass has to take into account the light that will be shining through the window and be planned for accordingly, but Denny's personal approach goes well beyond this. As he has said, "Stained glass must be interesting and beautiful in its own right, but it must always acknowledge its context." [1]

There are several parts to this context. The first is the building itself and its surroundings. Unlike other pieces of art that can be moved from one place to another, a stained glass window is completely rooted to its location; it isn't moveable art. So before Denny does anything else, he spends time in and around the building where the glass will be installed. He looks at the colors already present, the stonework, the architecture of the building itself. And of course there is the light to consider, not just the light that will come through the window, but light from the front (bright lighting opposite a stained glass window will cause glare off the window so that colors don't show well). The light from behind and the light the window will cast into the space in front of it onto people and spaces and structures are all parts of the multi-dimensional art of the stained glass window. The light creates art that is ever-changing, never static, and incorporates the viewer. I remember standing in the light from a window in the Chartres Cathedral in France as the color fell over me; I was enveloped into the art in a way that made me a participant rather than merely an observer.

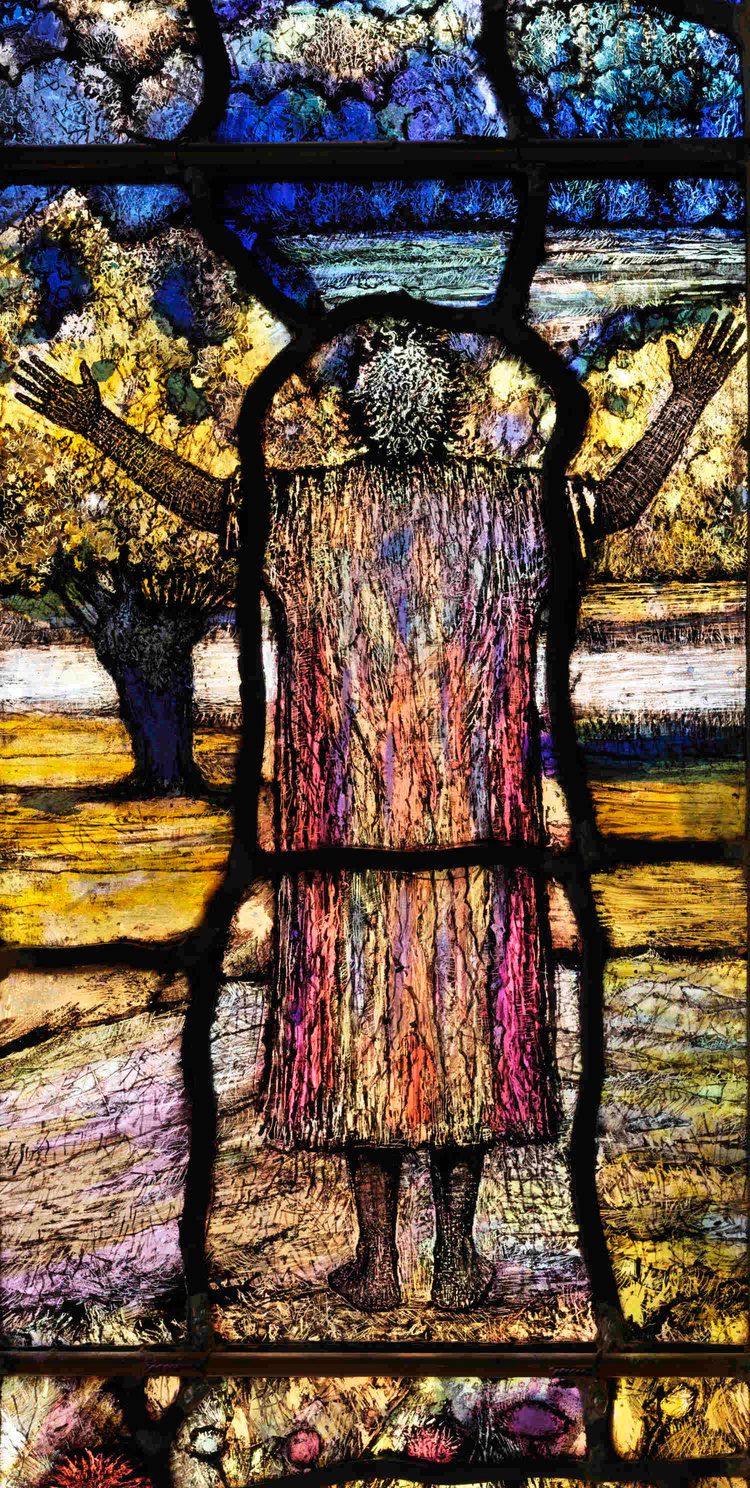

Denny also sees the context of surroundings as integral to his work. He walks every day in the countryside where he lives, "walking slowly, almost comatose, in a serene state akin to prayer." [1] It is common for him to notice intricate, beautiful objects that he will remember and store up for his work. He sees the land around him as sacred and this shows in his work, and in the people who populate his windows.

“My people are turned towards something revelatory. But the earth itself is revelatory.”

When he has a commission, an important part of his preparation work is to walk the countryside and see what is present there. He then incorporates the landscape and community into his work, making the window specific to its particular place. I love this rootedness. There is a congruity to our work when we do it for a particular place and time; it contains a humility and integrity that goes deeper than ambition or abstract ideas.

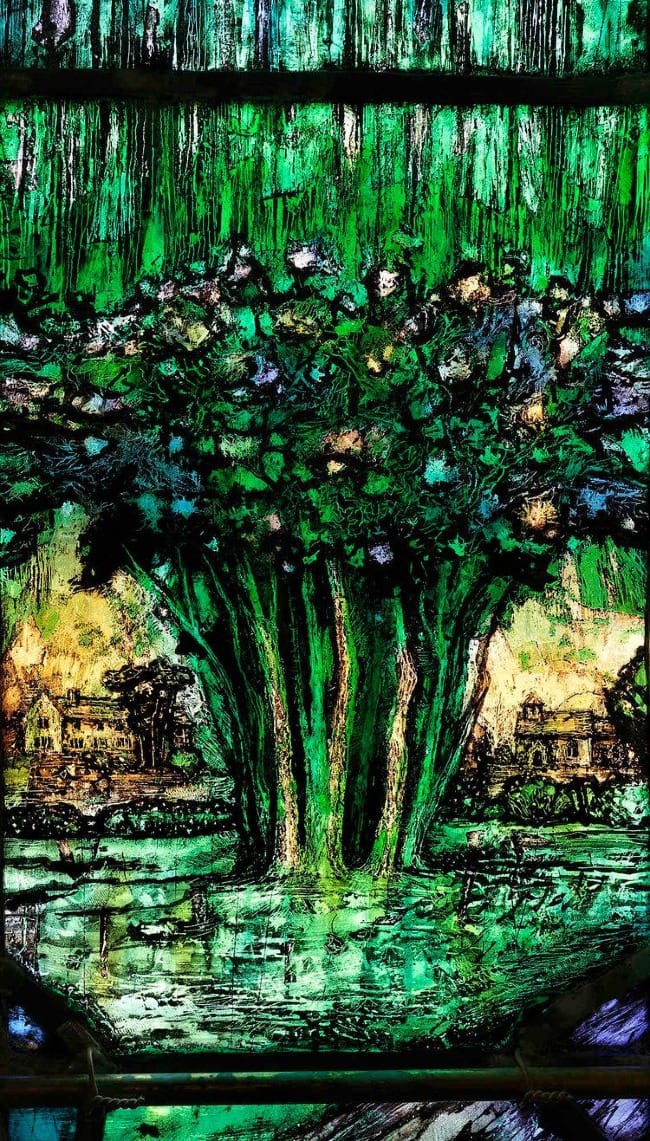

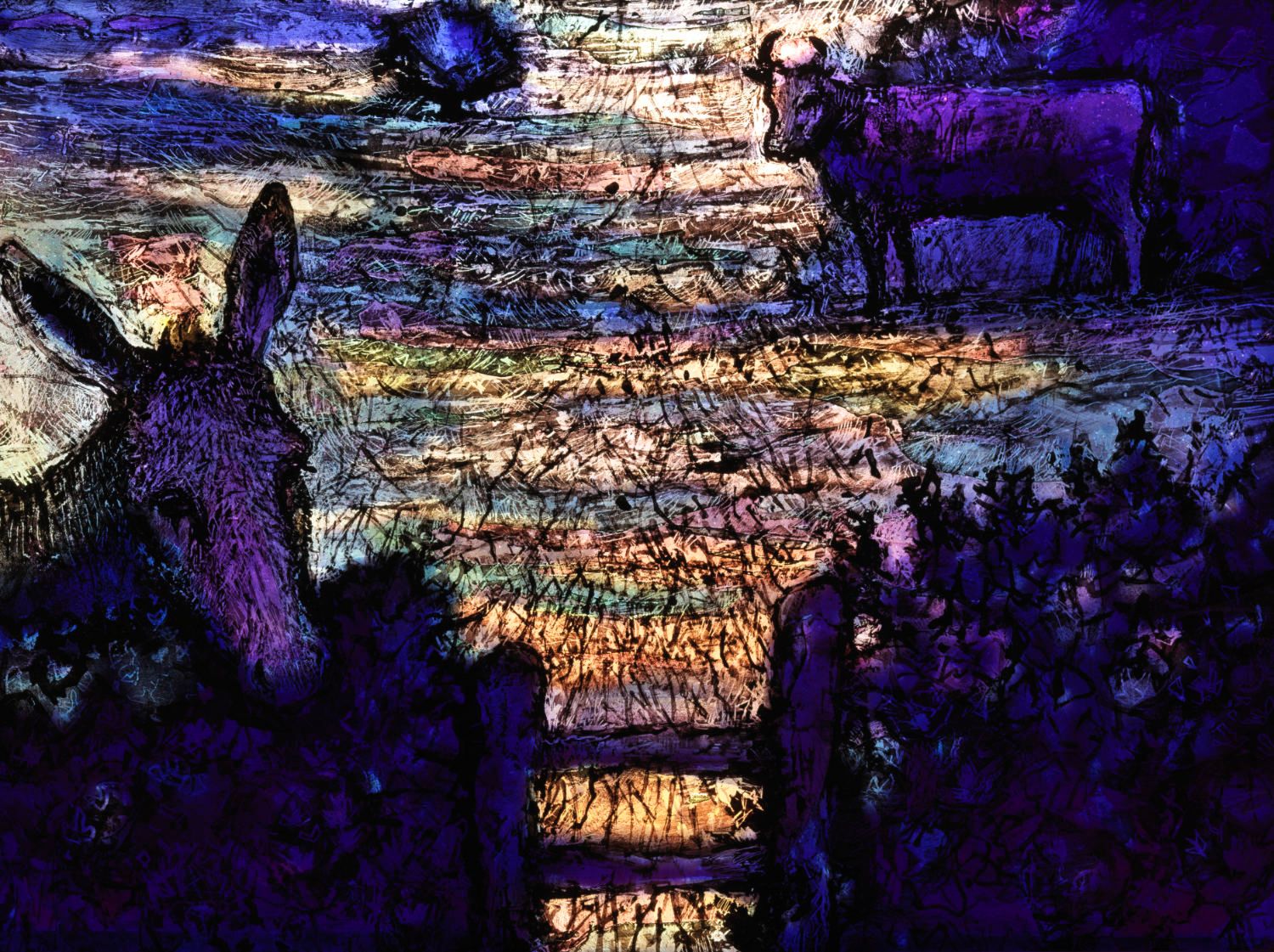

You find this particularity in the memorial windows he creates, in which he adds specific people to the elements of particularity of location and place. For instance, one of the window from St. Paul's Church in Shurdington, Gloucestershire below, gives us a picture of the beauty of creation (many of his windows are illuminations on Psalms of praise), but also embodies it in concrete ways that honor the people who inspired the windows—in this case a former churchwarden who especially loved donkeys. Thus, a donkey is central to this particular window.

St. Paul's Church, Shurdington

In window after window, a specific life and place are included both in themselves, but in addition as examples through which we see a way to greater meaning and value, perhaps even as an example of how we might use that example as a guide for ourselves.

In the windows he made to honor Ivor Gurney, a World War II poet who, after returning from World War II, struggled with deep depression and grief, this is taken even further. With grace and honesty, the windows show pictures of a person's mental struggles being lived out in light of God's presence and glory. This is far from disembodied or "heavenly" art; it is rooted in the truth that humans are embodied people and that living our lives on a particular piece of ground is complicated, real, and sacred. Larger meanings and truths can be learned and carried away, but they spring from particulars not abstractions. This church stained glass is reflective of real lives lived by real people, with God's glory shining through, much like light shines through a stained glass window, changing moment by moment. And Denny himself embodies this journey, saying, in a video,

"The process of working is like the process of prayer. In many ways, the most intense part of my spiritual life is grappling with my windows."

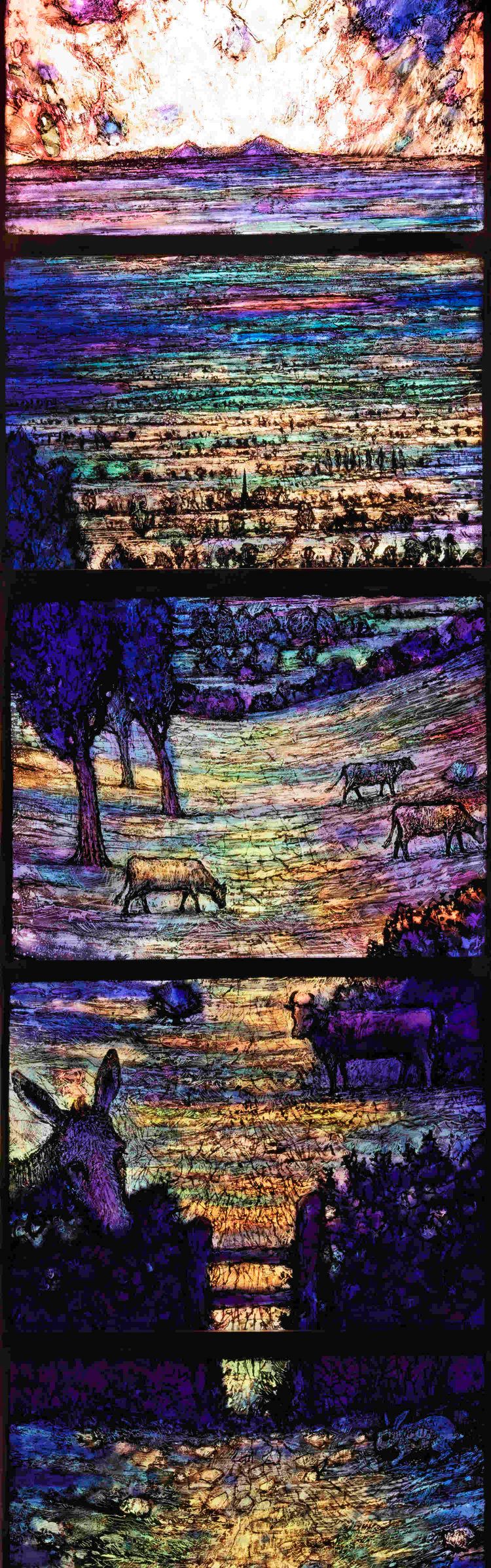

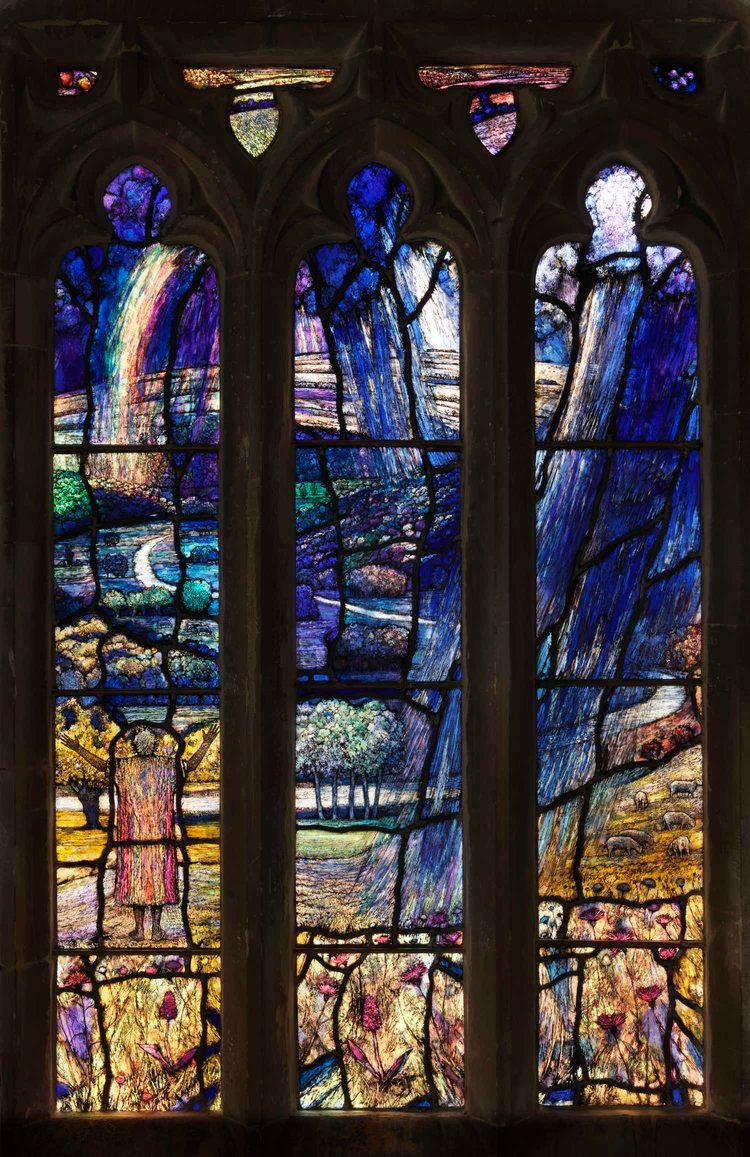

Most of his stained glass is fundamentally grounded in scripture. You see this in his windows from All Saints Church in Lower Woodford, which illustrate Psalm 65 and are pictured below.

The grasslands of the wilderness overflow;

the hills are clothed with gladness.

The meadows are covered with flocks

and the valleys are mantled with grain;

they shout for joy and sing.

All Saints Church, Lower Woodford, Wiltshire

When Denny includes the countryside, he incorporates what is actually present in that place. For me this brings home the truth that scripture is real and applicable to our own time and place. It isn't just the ancient Jewish countryside that praises God; it is our cattle, our sheep, our thistles, our ravens that continue to praise God. It is our fields that are clothed with gladness, our meadows that shout for joy and sing. I love how this makes the scripture immediate to our own time and place.

In his work at St. John's Tralee, in Ireland, called The Window of Reconciliation, Denny brought his own family history into the work. His family (the Dennys of Tralee Castle) owned much of the land around Tralee until gambling debts forced them to sell it off and leave Ireland. The themes of the Window of Reconciliation, with a central panel featuring the Prodigal Son, are reconciliation, healing and renewal. The work, a joint endeavor of Tralee's Catholic parish the Church of Ireland parish, is a memorial to the Good Friday Agreement of April 10, 1998 which ended most of the violence from "The Troubles" which had racked Northern Ireland since the 1960's. The window signifies reconciliation after conflict between Protestants and Catholics in the area. Denny names this as possibly his most significant work of art:

"Can a work of art do something significant? Can it really be part of the process of reconciliation? It can at least be a field for contemplation."

Denny's craftmanship itself is extraordinary and fascinating. The process of creating stained glass is long and involved and, for the most part, he uses the same techniques and materials that were used in the 14th century. From beginning to end, the creation of windows takes Denny at least six months, even for small windows. It involves glass-cutting, acid-etching, silver-staining, painting, firing, leadwork (which is done by a collaborator of his), and installation. He sees himself primarily as a painter and you see that in his work. His pieces of glass are not just colored and textured, they are painted upon. Rather than the leadwork providing distinct boundaries between colors, which is most usual in stained glass, his pieces flow from one section to another, creating a piece that is, again, anything but static. He admits to favoring the less-than-tidy, the shaggy, the slightly unkempt. He favors bare feet, shaggy hair, and orchards over gardens.

Reflection Questions: How is your work rooted in your particular place and time? What affect does this have on the work that you do? Do you have practices of observation and immersion that serve as a type of prayer for you?

Louise

Feel free to contact me directly at info@circlewood.online.

To see more of Thomas Denny's work visit his webpage.

Follow this link to watch Denny talk about his art and the Reconciliation Window.

[1] Denny, Thomas. https://www.thomasdenny.co.uk.

[2] Cazalat, Mark. Walking Man: The Art of Thomas Denny, Issue 86. https://imagejournal.org/article/walking-man-art-thomas-denny/