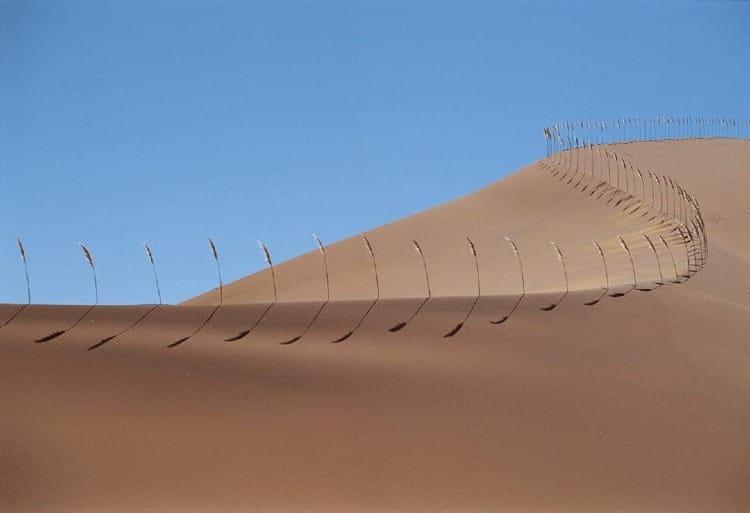

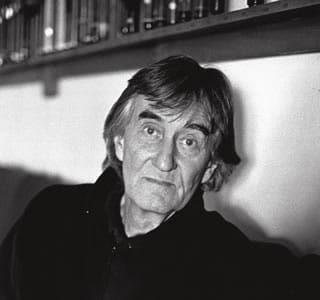

You can find photographs of German artist Nils-Udo's work in art galleries, but viewing the original pieces which the photographs capture might require some tramping and some very lucky timing to see in person. Commonly classified as an environmental artist, much of his work fades or changes soon after it has been created, so that only the photographs remain. While some environmental artists rearrange the landscape to create massive works of art, his work avoids disrupting the environment, creating work that fades back into the landscape over time.

Tools of the Trade

Not only won't you find his original work in art galleries, neither will you find his art supplies in art catalogs, since the tools he uses are what he finds on hand. For the outdoor installations that make up the bulk of his work, this means materials such as snow, flowers, leaves, berries, twigs, water, stones, and sand.

"Sketching with flowers. Painting with clouds. Writing with water. Tracing the May wind, the path of a falling leaf. Working for a thunderstorm. Awaiting a glacier. Directing water and light." That is how describes his own work.

One benefit of using only items from the area he is working in is that he avoids harming the place with non-native or other potentially harmful additions to the local ecosystem.

Although he has painted on canvas using tubes of paint in the past (and recently picked it up again), for much of his career he has steered away from manmade canvas and art supplies, feeling it to be an artificial way of handling nature. He prefers instead to "work at the source itself."

In an interview, he describes the change in this way: The idea of planting my work literally into nature - "of making it a part of nature," of submitting it to nature - its cycles and rhythms, filled me on the one hand with a deep inner peace and on the other with seemingly inexhaustible new possibilities and fields of action, putting me into an almost euphoric state of readiness for new departures. As a part of nature, I lived and worked day after day in its rhythms, by its conditions. Life and work became a unity. I was at peace with myself. The decade long abstract struggle in front of the canvas with the subject of my life - nature - was now past. Nature's room itself was to be my art space."

He describes his process as one in which he comes with empty hands, even without the conceptual idea of what the project will look like. This he gathers from interaction with the land on which it will be placed.

I never arrived somewhere with a preconceived idea, my work always reacts to the natural surroundings I’m confronted with.

Because he uses living subjects, which develop and change, the work is subject to deterioration, which can take anywhere from seconds to years. A project made of ice may last a season; if made of flower petals or leaves, it may only last until the next blast of wind or a changing tide. Because it is a living piece of art, it is also temporary.

The Recurring Nest

For many years, a recurring theme in his work has been the nest. He has made nests in many different environments, out of many different materials. He has created nests with eggs, nests without eggs, nests with people curled inside them, (such as the one for Peter Gabriel's album cover pictured below) nests of bamboo, sticks, grass, branches.

One of his most recent works, "Habitat," is comprised of three giants "nests" on poles in a French vineyard, created from vines from the vineyard and branches from black pines that are being removed in order to create more biodiversity. His goal (and that of the vineyard owner) is that these nests actually get used, that they create habitat for birds, insects, pollinators, and other creatures. An image of one of the nests can be seen at the top of this article.

This work, in which the "nest" is not merely a representation of the idea of nests (places of shelter, continuance of nature, procreation), but is literally becoming a nest for creatures, is a further step in the art being integrated into its environment. It is not just pointing to the theme, but becoming the theme.

Revealing What is There

Nils-Udo states firmly that he doesn't create beauty with his work; he just makes the beauty inherent in the place more visible to people. He even laments at times that he is destroying some of the inherent beauty when he disrupts the natural world with his art.

“Even if I work parallel to nature and only intervene with the greatest possible care, a basic internal contradiction remains. It is a contradiction that underlies all of my work, which itself can’t escape the inherent fatality of our existence. It harms what it touches: the virginity of nature… To realize what is possible and latent in Nature, to literally realize what has never existed, utopia becomes reality. A second life suffices. The event has taken place. I have only animated it and made it visible.”

Because he is intent on showing the beauty already inherent in a place, there is a consistency and urgency in using what he finds there. It would be a contradiction to his philosophy of merely bringing to light what is already there if he were to impose imported materials and subject matter on a particular place.

I tried to find an idea on-site which allows me to open up hearts and eyes to nature’s reality...

Part of Nature

Because humans are part of their environment, Nils-Udo’s sees his own interactions with an environment as an interaction of a human upon himself. He finds this close association deeply satisfying and transformative.

Henceforth my pictures were no longer painted, but planted, watered, mowed, or fenced. Through my plantations, I associated my existence with the cycles of nature, with the circulation of life.

Nils-Udo has stated that his artistic experience underwent a major and amazing change when his artistic process shifted, that the potential of his art expanded into limitless possibilities. I think that same shift can happen to any of us when we begin to look at what is around us, not at a place to impose our own preconceived ideas upon, but as a place to explore, learn from, and nurture, highlighting and supporting what is already inherent in that particular place.

Reflection Questions: Are there times or activities that particularly help you feel yourself to be a part of your environment, rather than a being who is separate from it? How does thinking of yourself as part of your environment affect your everyday actions?

You can learn more about Nils-Udo and see more of his work at his website.

Feel free to leave a comment below or contact me directly at louise.conner@circlewood.online.

Louise

Want to learn more?

Find out more or support our parent organization by clicking below.