When thinking of well-known wildlife artists, John James Audubon is often the name that comes immediately to mind. His realistic detailed portraits of birds have habitually set the standard for other wildlife artists. Charley Harper, who lived from 1922 to 2007, was a different kind of wildlife artist, however, and he quipped that he was probably the only wildlife artist who had never been compared to Audubon.

Minimal Realism

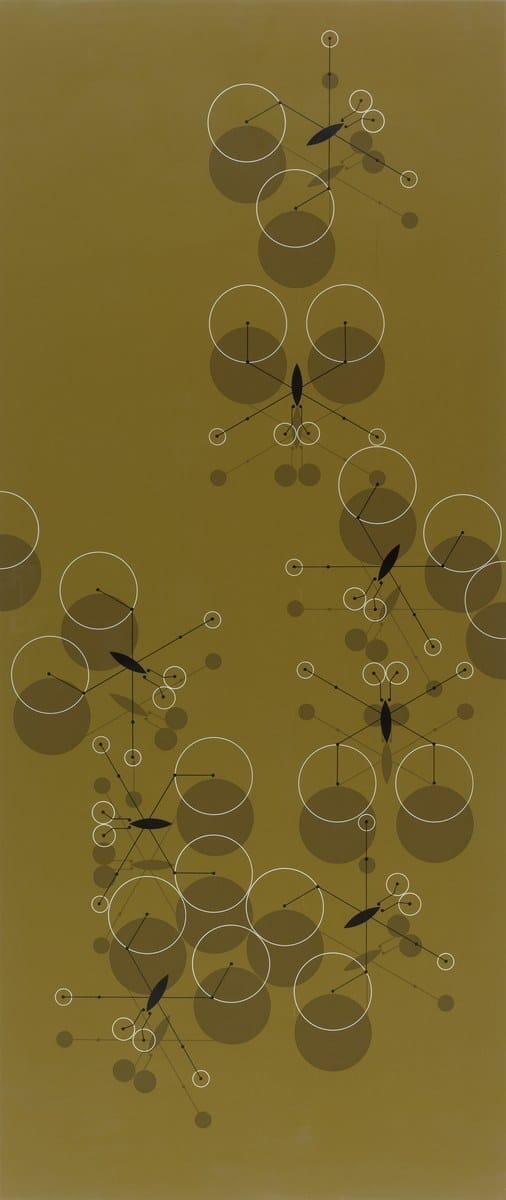

Harper's portraits approach his subject matter differently than Audubon and most other wildlife artists. As he said, “I don’t see feathers, fur, scapulars or tail coverts—none of that. I see exciting shapes, color combinations, patterns, textures, fascinating behavior and endless possibilities for making interesting pictures. I regard the picture as an ecosystem in which all the elements are interrelated, interdependent, perfectly balanced, without trimming or unutilized parts; and herein lies the lure of painting: In a world of chaos, the picture is one small rectangle in which the artist can create an ordered universe.”

Dubbing his art “minimal realism,” he distilled what he saw down to geometric elements, using an architect’s or engineer's tools like T-squares, compasses, rulers, curves, and straightedges to create his work. This distillation wasn’t due to an inability to create realistic pictures; he began his career by creating very realistic pictures but began to lose his interest in this approach. This skill wasn't wasted, however, for as he said, “You’ve got to know how to put everything in before you will know what you can leave out successfully.”

Essentially, Harper said it was the difference between painting the thing itself or painting a picture of the thing. "I didn’t start out to paint a bird – the bird already existed. I started out to paint a picture of a bird, a picture which didn’t exist before I came along, a picture which gives me a chance to share with you my thoughts about the bird. Once you accept this seemingly simplistic but really quite profound premise, you will appreciate the many varied approaches to the making of pictures, all of which start where realism leaves off, but all of which require an understanding of realism for their successful execution.”

This is both a humble position and a bold one, for it approaches art from the stance that the artist's perspective is the reason for the art. He is not trying to show the bird to you in exact detail, but instead communicating his particular perspective on the bird.

Parts of the Whole

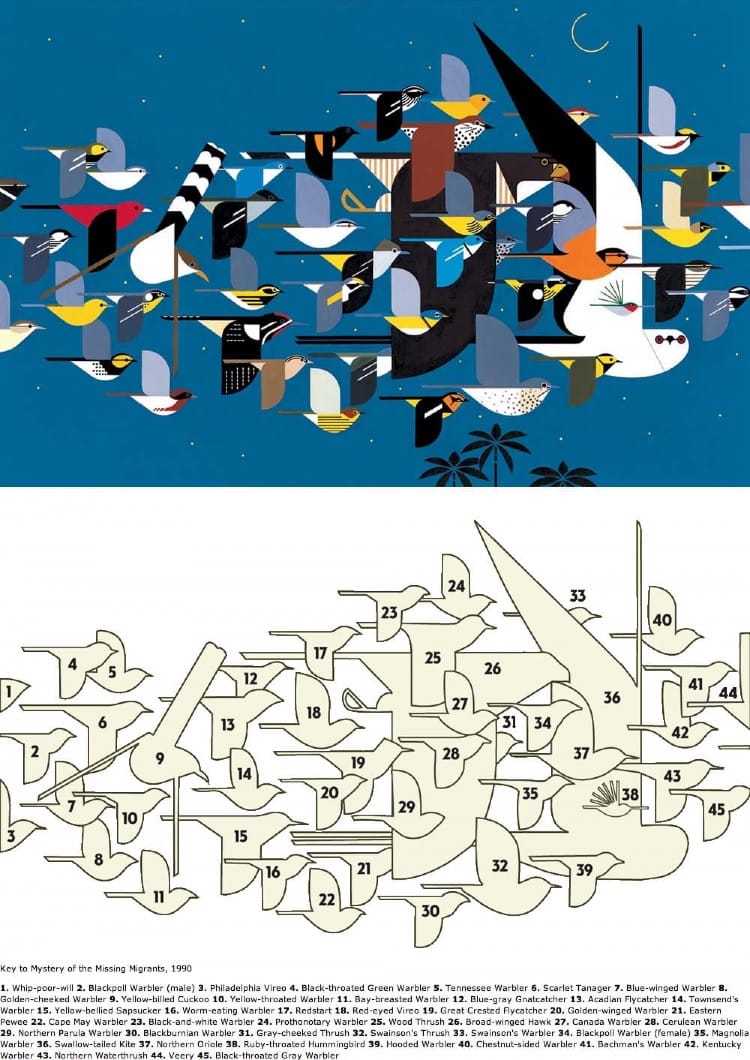

When Harper created his pictures, he took pains to place each species where it would naturally be found, recognizing that a creature's place is an important part of their identity. If, for instance, he was creating one of his many bird pictures, he would learn about the bird's way of life and habitat, how it interacted with other creatures, what made that bird unique. All of this shaped the pictures of that creature. He would attempt to capture entire ecosystems in a single illustration, something he said he had learned about from drawing combat scenes in the midst of battle during WWII and when trying to paint the Rocky Mountains onto a single piece of paper during a honeymoon trip.

The Humorous Side

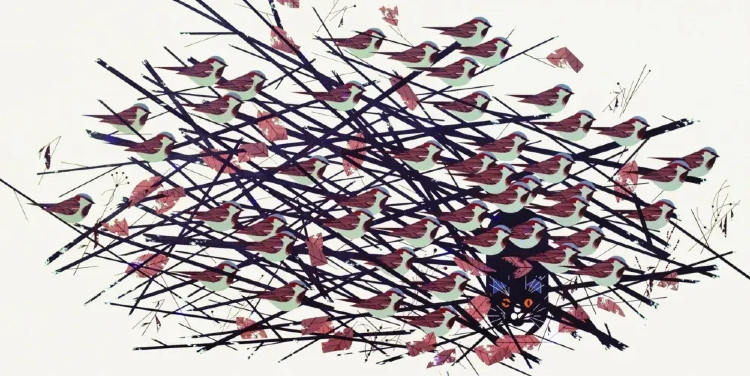

An important part of Harper's perspective was the infusion of his sense of humor into the art. The titles of his works were often a play on words or a pun of some short: "Antypasto" (A woodpecker pecking for ants), "Serengeti Spaghetti" (a group of zebras huddled together), "Raccoonnaissance" (a bunch of raccoon eyes peering over a woodpile at a skunk), and "Poached Eggs" (raccoons stealing eggs as quickly as a turtle lays them), are examples of his use of verbal humor.

He would often play with perspective, creating pictures from an unusual point of view, which he then combined with a humorous title. The result was a picture that could create a smile, and also present an offbeat, but true glimpse into the interactions of other creatures in creation.

After an artist friend suggested that his art was well-suited to silk screen, he began printing serigraphs of his work, which developed into an important aspect of the reproduction of his art. He also wrote short stories that accompanied many of his pictures, which would tell something about the creatures in the pictures and also add a dose of humor.

"Jesus Bugs" (called so because of their ability to walk on water) had this paragraph as its accompaniment: Can you think of a better name for insects that walk on water? Our ancestors couldn’t either, but your field guide calls them water striders. They hike around on the pond all their lives without even getting wet feet, and in shallow water on a sunny day their shadows sink like stones and tag along on the bottom. But who minds a wet shadow? If you had wide-spread, waxy feet that didn’t break the surface film, you, too, could walk on water. And be famous for fifteen minutes!

The Serious Side

More and more as his career progressed, humor became part of a serious attempt to encourage conservation, for he believed humor helped the effort to change attitudes toward environmental concerns. By the 1970's he had moved away from the work for companies such as Betty Crocker and Ford Motor Company that had filled much of his time and moved toward accepting commissions only from organizations that shared his concern for the environment.

This led to a set of ten posters for the U.S. National Park Service, work for the Audubon Society, the Cape May Observatory and other like-minded organizations. He explained it this way:

"...the more I become involved with it, the more I am troubled by unanswerable questions about our exploitation of plants and animals and our casual assumption that the natural world is here only to serve people. I have to ask myself how man, the predator with a conscience, can live without carrying a burden of guilt for his existence at the expense of other creatures... Maybe all of this is why my pictures are usually humorous—I'm laughing to keep from screaming.

This question is an important one for all of us to keep asking each other and ourselves as the existence of other creatures as well as ourselves becomes increasingly tenuous. How do we live with other creatures in a way so that both we and they thrive?

Although Harper worked in his craft for 60 years, it wasn't until near the end of his life that his work became known outside his nearby community. This happened when an MTV designer named Gary Oldham who had always admired his work, archived it and turned it into a book called Charlie Harper, An Illustrated Life. Now, his art is everywhere, helping people see the world in a more whimsical, humorous, and ecological way.

You can find much more information about Charley Harper's life and work at a website maintained by his son Brett Harper. It also includes information about Charley's wife Edie, who was a fellow-artist. Products, books, and prints can be ordered from this website as well.

Feel free to leave a comment below (you can sign in through your email) or contact me directly at louise.conner@circlewood.online.

Louise

Want to learn more?