Soaking in a Georgia O’Keeffe painting can be as refreshing as a spell of idleness can be for people with overly busy schedules. It provides a chance for sustained observation, based in a healthy pause, not observation merely for the sake of coming to a conclusion or drawing a parallel or making a statement. There is something in these paintings by O’Keeffe that suggests that a person look and look again, sitting with the observation for a while and leaving room for curiosity to see if their perception changes—to look without an agenda or a plan.

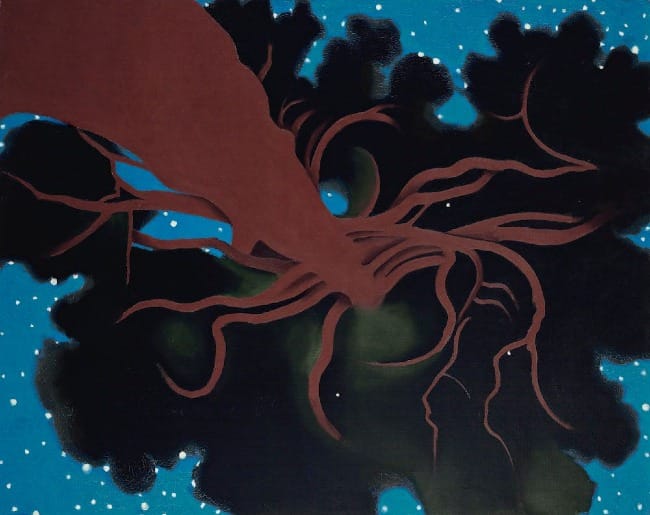

The Lawrence Tree

The Lawrence Tree in particular invites the onlooker to approach it in this way. How else to approach a painting where the artist is obviously lying on her back looking up at the trunk and branches of the tree from a recumbent position. It’s hard to ignore the position from which the tree is painted from, and the association of this position with childhood memories of lying on the grass, looking up at a tree with leisure and awe, is strong. It doesn't suggest a position of power or an agenda of important tasks to be done. The viewer is small; the tree is large. The viewer is on the ground; the tree is stretched across the sky, branches reminiscent of arms, like a strange oddly serpentine-armed creature standing outstretched against a background of the starry night sky. There is a distinct attitude of humility and amazement on the part of the looker in relation to the one being looked at.

It is nighttime and the viewer is beneath the tree. Can you place yourself in that scene? The tree dominates the picture, with the sky merely peeking out from between branches and leaves. The tree intercedes between the viewer and the huge expanse of sky, and in some ways mediates the viewer's presence underneath the sky. The tree overshadows and informs the experience, while the sky is seen only in relation to the tree, not independent from it.

I, myself, have huddled near trees and felt their power, as well as a safety prompted by my nearness to their large presence. During windstorms, I have huddled close to tree trunks, feeling safer in their shelter, even knowing that proximity also created danger from falling branches. In spite of this potential danger, the nearness has increased rather than decreased my sense of safety. The tree in this painting reminds the viewer of their smallness, their position of vulnerability to power greater than their own, but the tree comes across as protecting, rather than threatening.

The Ponderosa pine featured in this picture is a specific tree that has a notoriety of its own, even apart from this painting. It is located near a cabin in Taos, New Mexico on the well-known Kiowa Ranch, where the author D.H. Lawrence lived and where an artistic community sometimes gathered. The Lawrence Tree was photographed by two National Geographic photographers who included it in a book featuring 50 historically important trees from around the world. I think knowing this emphasizes that the tree is significant in its own right, not just as the subject of this painting.

The proper direction this picture should be hung is a long-standing controversy. Originally, at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum, it was hung 90 degrees to the right from what is pictured above until, after a number of years, they shifted it in the direction pictured above. This change was based on what was believed to be the artist's preference. After O'Keeffe completed it, she stated many times that the tree should "stand on its head." To me, this orientation feels right as it is what you would see if you were lying down, looking up at the tree. The perspective is meant to be disorienting, in the same way that craning your next to try to see the top of a tree from directly below is disorienting. Stare up enough at the top for a while and it can make you dizzy, which is the feeling this painting creates as well.

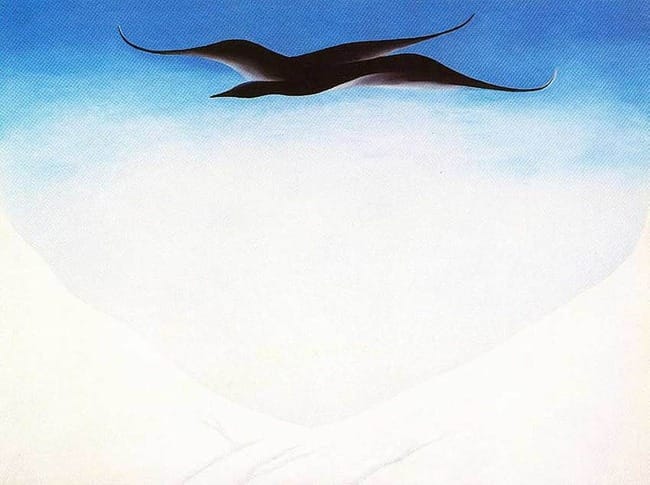

A Black Bird with Snow Covered Red Hills

The other picture I include in this post is, "A Black Bird with Snow Covered Red Hills." First of all, I love the title. The hills, though covered with snow are, in the mind of the artist, still red in their essence; they only appear to be white because of the cover laid upon them by the snow. This suggests a view that sees past appearances into the reality of a thing. Snow may come and go, but the hills are still red, even if that isn't visible to the observer's eye. Dig down through the snow and you will find the red of the hills. The snow is just a temporary covering, not part of the hills themselves.

The styled curves of the black bird and its darkness against the blue is startling. The white snow reflects a bit on its underside and its body shape is representative rather photographic. It threads the line between white and blue, separating the ground from the sky, beautiful, smooth, sweeping upward with its curving stylized black feathers.

As with The Lawrence Tree, the point of view is from down below, looking upward—in this case at the bird. In the same way that the tree intervenes between the viewer and the sky in the other picture, the bird intervenes between us and the sky in this picture. The bird's dark shape is the central focus of the picture, even as it inhabits the top rather than the center of the canvas. The bird draws our eyes and attention to the top of the picture, where the white melts into blue, where the sky reaches up and up into space outside the picture.

Again there is the sense that we are seeing something that has power we don't have, in this case the power of flight, freedom, and space. We are creatures of below, the bird is a creature of above. The view from below, looking up, reminds us of those things that are in some ways beyond us, those things that are larger than us, including time, space, and perhaps, depending upon our own held perspective, the creator that holds all of this within his power.

With both of these paintings, O'Keeffe invites us to pause, look, and feel the sky above us and the creature that is between us and that sky. Our perspective is not as if we are the tree or the bird, and yet they translate the scene for us, reminding us, as they rise above us, that we are creatures of the ground and that it is not an altogether bad thing to feel a little smaller as a result of that recognition.

Reflection Questions: What have you seen recently that reminded you of things larger and more powerful than you? Did this reminder comfort you, make you afraid, or both?

Louise

You can contact me directly at info@circlewood.online.