We're excited to share another post from Abigail Welborn, who is an Ecological Disciple subscriber, writer, and supporter of Circlewood (our parent organization). As a follow-up to her last post, she shares some ways that she started greening her family's vehicles! Enjoy.

Now that we’ve talked about greening our lives and homes, let’s talk about greening our vehicles! My family now has two electric vehicles, or EVs, and we’ve learned a lot. To keep this post short(er), I’ll be linking to a lot more info and focusing on personal experience.

Why Electric?

Transportation is the largest domestic contributor to climate change. EVs are, on balance, much greener than gasoline-powered internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs). Most of us don’t live in a transit-friendly or walkable neighborhood, so if you have a car, switching from an ICEV to an EV significantly reduces your emissions.

Except for the up-front cost, EVs are no sacrifice; they’re just plain fun to drive. I don’t miss gas stations at all—not the smell of gasoline, nor having to leave the house to fill up.

Finding and choosing

The best way to get a handle on what EVs are like is to drive some. We did some test-drives at a free local event. EV owners were honest with us about the pros and cons of their cars, and the dealerships didn’t put on sales pressure. If you’re interested in EVs, look for a Drive Electric event near you, or find your local EV club on Facebook or NextDoor.

Purchasing and Maintaining

Unfortunately, EVs are still expensive. While they cost less to drive and maintain, they cost more upfront than ICEVs.

More EV options become available every year—but new isn’t cheap. Whereas an ICEV like the Chevy Spark costs $15,000 brand new, the cheapest EV, the Nissan Leaf, costs twice that. A family-sized EV will probably cost in the low $40s, but at least there are multiple options (along with plenty of more expensive ones).

Fortunately, many EV models and US households qualify for a $7,500 federal tax credit, and your state or city might offer additional incentives. Some models also come with freebies; for example, a new Volkswagen ID.4 includes three years of free charging at certain stations.

A used EV is hard to find, but it will be reliable and you still won’t have to stop for gas. If you’re patient, you can find one for under $15,000. Plus, many US households qualify for a tax credit of up to $4,000 off that price.

However, be aware that if you have to replace an EV battery, it’ll cost you anywhere from $5,000 to $15,000. While batteries can last up to 20 years, make sure you know the warranty for the car you’re buying and whether it transfers to you.

Driving

I was blown away by how much cheaper they are to drive.

For maintenance, most only need occasional checks on the tires, brakes, and wiper fluid. By contrast, oil changes alone for ICEVs are recommended every 3,000 to 5,000 miles, with a cost of $30 and up. You also won’t have to replace EV brakes as often.

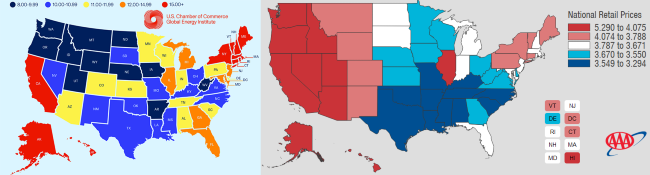

With fuel, EVs shine even more. Gasoline currently costs $3.50 - $4+ a gallon, and most cars drive 22-35 mpg, meaning a fuel cost per mile of 10-20¢, or higher for trucks and SUVs. If you drive 13,000 miles a year—the national average—that’s up to $2,600 just for gas.

Meanwhile, most EVs can drive 3-4 miles per kWh, while residential electricity prices average 8-22¢ per kWh (except Hawaii). If you charge at home, your electricity cost per mile will be 2-10¢. That means driving 13,000 miles for as little as $260!

Charging

Charging your EV at home will be the cheapest, especially if you get utility incentives to charge at off-peak times. We installed home charging stations for around $500, but all you really need is a 50-amp circuit, a 240V outlet (the kind used by electric ovens), and a plug adapter (which often comes with the EV).

Since a fuller battery fills more slowly, we only charge up to 100% on a road trip. Charging up to 80% takes less than 12 hours. Our family drives so little, we usually charge only once or twice a week—whenever we notice the battery dip below 40%.

Public charging comes in two varieties. Level 3 or “fast charging” powers up a vehicle in as little as 20 minutes. These stations cost 25-35¢/kWh, but you probably won’t need them unless you’re on a road trip or you drive for your job. Public fast chargers vary in speed, with 50kW of power charging relatively slower, while the fastest pour out up to 350kW—currently more than any EV can accept.

Public “destination chargers” are as slow as home charging. They can be found everywhere from store parking lots to your employer’s garage. You might have to pay, but they’re typically cheap and mostly for convenience.

What about road trips?

The value of an EV is clear, but most people hesitate, knowing they’ll eventually end up on a long car trip. The biggest change is planning your route before you go!

A full car and low or very high temperatures will reduce your driving range. Fast charging takes at least 20 minutes, up to 45, so we try to leave right after a meal to make our charging stops coincide with future meals.

An official range of 330 miles (our Tesla) allowed us to drive as long as I could make it between restroom stops anyway. In comparison, an official range of 230 miles (our VW ID.4) meant the car sometimes had to charge before the humans would have needed to stop.

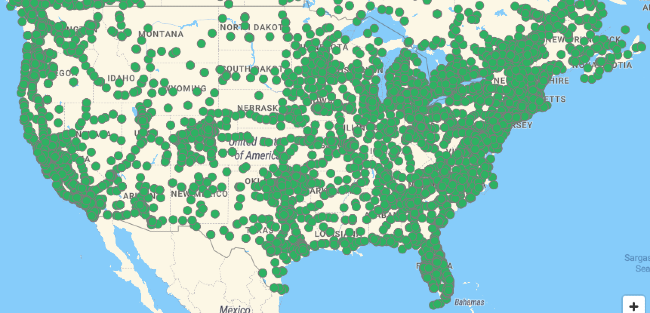

Most highways in the US already have enough infrastructure to road trip. EVs often have navigation built in, or you can choose from multiple apps to help you find public chargers—just make sure you’re filtering your view to 50+kW and the right plug (most cars use either Tesla or CCS).

Conclusion

A used EV with a modest range for daily commutes will put you well on your way to greening your transportation emissions. A larger and/or longer-range EV costs more for now, but prices will fall as popularity rises. Start planning now and look forward to never pumping gas again!

In my next post, we’ll talk rooftop solar!

Abigail Welborn

Get in touch with Abigail: Twitter or Instagram.

You can comment on this post below.