It is easy to overlook something as unobtrusive as lichen. It mostly fades into the background of a tree, a wall, whatever surface it is growing upon. But as this poem by Jane Hirshfield alludes to, the "unseen, unread, unremembered" do transforming work that makes life possible—both for themselves and others.

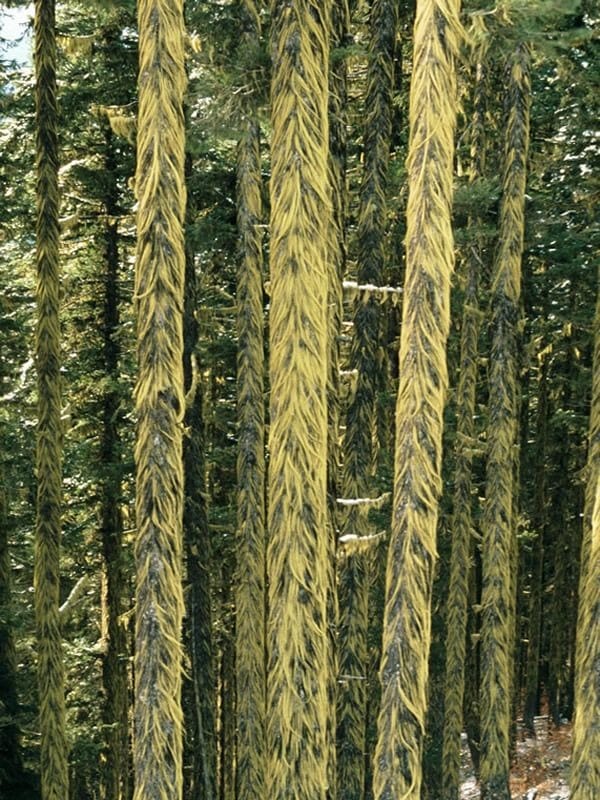

For the Lobaria, Usnea, Witches Hair, Map Lichen, Beard Lichen, Ground Lichen, Shield Lichen

by Jane Hirshfield

Back then, what did I know?

The names of subway lines, busses.

How long it took to walk 20 blocks.

Uptown and downtown.

Not north, not south, not you.

When I saw you, later, seaweed reefed in the air,

you were grey-green, incomprehensible, old.

What you clung to, hung from: old.

Trees looking half-dead, stones.

Marriage of fungi and algae,

chemists of air,

changers of nitrogen-unusable into nitrogen-usable.

Like those nameless ones

who kept painting, shaping, engraving,

unseen, unread, unremembered.

Not caring if they were no good, if they were past it.

Rock wools, water fans, earth scale, mouse ears, dust,

ash-of-the-woods.

Transformers unvalued, uncounted.

Cell by cell, word by word, making a world they could live in.

Copyright © by Jane Hirshfield. Originally published in Come,Thief (Knopf, 2011).

This poem is told from the perspective of someone who is initially oblivious to the environment around her beyond the immediate means of getting from one place to another. Oblivious even to what direction is north or south, her world consisted of "uptown" and "downtown," and the utilitarian world of subways, transportation, and work. Although, as she says, the lichen was already there, she didn't see it. She had other things on her mind.

Somehow, sometime, something changed. And she saw beyond the buses and subways. (Perhaps she began to walk to places). Once she began to see what was around her, she began to learn. And once she began to learn, she began to name what had before been unnamed to her: Lobaria, Usnea, witches hair, mouse ears, rock wools, ash-of-the-woods.

This change from unseen and unnamed to seen and named signifies an important shift, for it is when we begin to name and understand that appreciation and relationship begin to form.

From someone who perhaps didn't observe much around her (if she is the narrator of the poem), Jane Hirshfield has now become known as a poet who works at the intersection of poetry, the sciences, and the crisis of the biosphere. This is work that does not necessarily garner a lot of attention. It is, however, work that creates an atmosphere in which living things can grow—a world that can be lived in—like the transformers in the poem.

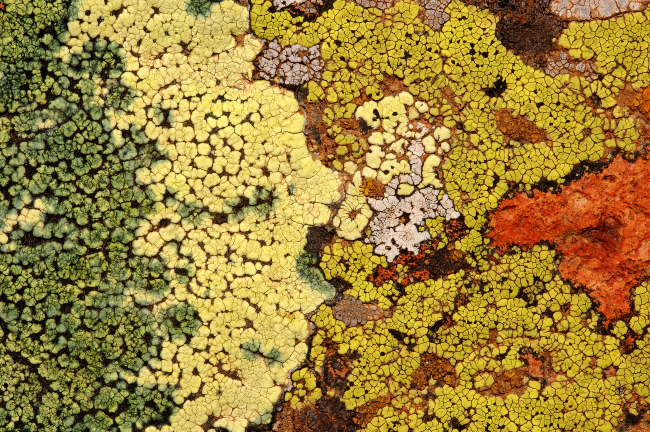

Sunburst lichen, Trumpet lichen, Dog lichen

Lichens, though often unobtrusive, are complicated. They are not single organisms, but life forms that are symbiotic partnerships between a fungus and an alga—the "marriage" of the poem. The dominant fungus determines most of the characteristics of the lichen, including its shape and its fruit, while the alga provides food through photosynthesis so that that the life form can grow and spread.

Like plants, lichens use cyanobacteria to "fix" nitrogen, changing it from an unusable form to a usable form. While plants such as legumes fix nitrogen from the soil, lichens fix nitrogen from the air, thus becoming "chemists of air."

Two forms of crustose lichen

Some lichen can also create the beginnings of soil. By releasing certain chemicals and by expanding and contracting their thallus (vegetative tissue) they break rocks down into particles, which, combined with the organic decomposition of the lichen when it decomposes and with dust, creates a rudimentary soil.

In the poem, we see the commonality between the aged lichen and all those aged creators who create whether they receive acclaim or attention or not. They create and transform because it is their nature to create and transform things, and this is their work, whether it is recognized and acknowledged or not.

What can we learn from lichen? Perhaps how to be steady and persistent, how to keep at something no matter how long it takes, to do what needs to be done when no one is watching and no one notices. How to enter old age with grace and continued purpose.

Reflection Questions: Do you notice and value the less-flashy members of creation? How do you see yourself helping make a world in which you and other creatures can live? How do your creative acts look or not look like those of the Creator God whose nature it is to create and sustain life?

Feel free to comment below or contact me directly at info@circlewood.online.

Louise

Hirshfield is currently the curator of a participatory exhibit called, "Poets for Science," on which website visitors can find a collection of wonderful poems exploring connections between poetry and science, contribute their own lines to an "I Pledge My Allegiance" global community poem, and visit a Listening Wall where they can listen to poets read their poems, which the reader can then use to create their own poem from the words that are spoken.