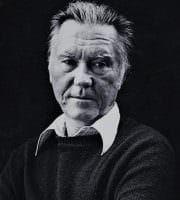

Poet William Stafford (1914–1993) was a writing mentor to me (and others) even though I never attended a class under him. His words to blocked writers, "Lower your standards and keep writing," defused the tension with wry humor and encouraged the doggedness often necessary when writing was difficult. He was a writer whose consistent and genuine voice made the practice of writing and reading poetry more accessible when poetry sometimes felt inaccessible.

A committed pacifist, Stafford was a conscientious observer during World War II, working in Civilian Public Service camps. He was connected to the historic Peace Churches of the Church of the Brethren and the Quakers. He was appointed to the post of Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (a position now called the U.S. Poet Laureate) in 1970 and was the Poet Laureate for the State of Oregon from 1975-1990.

Stafford's poetry comes out of a deep affection and respect for the world around him, and focuses on paying attention to and learning from the natural world. He believed that nature is a powerful teacher; in this he has also been a mentor to many writers and observers of the world.

The Well Rising

By William Stafford

The well rising without sound,

the spring on a hillside,

the plowshare brimming through deep ground

everywhere in the field—

The sharp swallows in their swerve

flaring and hesitating

hunting for the final curve

coming closer and closer—

The swallow heart from wingbeat to wingbeat

counseling decision, decision:

thunderous examples. I place my feet

with care in such a world.

© 1960, William Stafford, from The Darkness Round Us Is Deep, HarperPerennial.

In The Well Rising, Stafford describes a world brimming with life and intent. The movement of water, dirt, swallows, are all "thunderous examples" of how to live thoughtfully and purposefully in the world. The well rises without sound; a swallow turns through air generating little sound, but even in that quietness they each communicate "decision, decision." These "thunderous" examples do not cower with the volume of their voice; they are thunderous to one whose eyes are open to reading and interpreting the world around them. Significance is often found in the quieter corners of the world.

The poem is an exploration that leads to a conclusion that the earth is a hallowed place that can be observed and learned from. The poet's observations lead him to approach this earth with a tenderness and respect: "I place my feet/with care in such a world."

Listening

by William Stafford

My father could hear a little animal step,

or a moth in the dark against the screen,

and every far sound called the listening out

into places where the rest of us had never been.

More spoke to him from the soft wild night

than came to our porch for us on the wind;

we would watch him look up and his face go keen

till the walls of the world flared, widened.

My father heard so much that we still stand

inviting the quiet by turning the face,

waiting for a time when something in the night

will touch us too from that other place.

© 1960,William Stafford, from West of Your City,Talisman Press.

In his poem, Listening, Stafford recollects his father's unusual capacity for hearing and interpreting the sounds of the natural world. This listening is more than audial. It is an attention, a joining with something other than yourself through an identification that widens the listener's world. Through listening, we are drawn into profound knowledge and connection to the world around us.

Perhaps the most important part of being able to really hear is the attitude that the world is worth hearing—that a sound we are curious about or don't understand is worth taking time to stop and listen to. Stafford describes how "we" (I believe this refers to Stafford and his family) would see his father's "face go keen/till the walls of the world flared, widened." Stafford deeply valued this ability of his father's to listen and learn, to form connections with the world around him. His father was a mentor to him in how to listen well.

The poem describes a sort of quest by Stafford to find a way to experience that same connection that his father had to the world around him. The deep listening described in the poem pays tribute to the way it can expand us if we are able to allow our attention and interest to be absorbed by other creatures in the world. It also voices the yearning for that deep understanding, an understanding I believe Stafford himself eventually found and modeled to others.

A recording of Stafford reading this poem is below.

At the Un-National Monument Along the Canadian Border

by William E. Stafford

This is the field where the battle did not happen,

where the unknown soldier did not die.

This is the field where grass joined hands,

where no monument stands,

and the only heroic thing is the sky.

Birds fly here without any sound,

unfolding their wings across the open.

No people killed—or were killed—on this ground

hallowed by neglect and an air so tame

that people celebrate it by forgetting its name.

© William Stafford,1998 by the Estate of William Stafford, from The Way It Is: New & Selected Poems.

This third poem challenges ideas of what makes a place worth memorializing, what makes a ground hallowed.

Stafford suggests that a place of peace is as hallowed (or more hallowed) than a place that has seen conflict and warfare. Where the "grass joined hands," where heroics weren't needed, where no bloodshed took place, with "air so tame that people celebrate it by forgetting its name"—that is a place that is truly hallowed.

We typically memorialize the places of battle and loss, overlooking ground that has been left in peace. In our minds, a place becomes significant when it has become the scene for some dramatic human struggle. The scarred places that have healed are celebrated, but less so the places that haven't ever been scarred.

The poem reminds us of the places where peace has been commonplace and undisturbed, where the sky is "the only heroic thing." This kind of ground is hallowed by "neglect" and peace, not clamoring death or grief. If we can see the hallowed nature of land that reflects the unity of the world rather than the historical division and opposition brought about too often by humans, perhaps we will move a little more toward the love of peace and a little more away from the love of war.

Like the other two Stafford poems, we are invited to listen to the world—attentively, curiously, lovingly, patiently. For when we listen, it can change what we see as valuable and constructive. I expect that we will find that this act of listening, and being mentored, will be one of the most important things we do.

If you want to explore Stafford more, you can listen to him speak about and read this poem below. You can also find more of his work here.

Reflection Questions: Where have you found mentors for how to listen well? What does the Creation teach you about itself, yourself, and/or God? Are there practices or mentors you can learn from to develop as a listener and a learner?

Feel free to leave a comment below or contact me directly at louise.conner@circlewood.online.

Louise