Contemplation and activism come together in the work of Homero Aridjis, Mexican writer and environmental advocate, who uses language to see, love, and protect the world we live in.

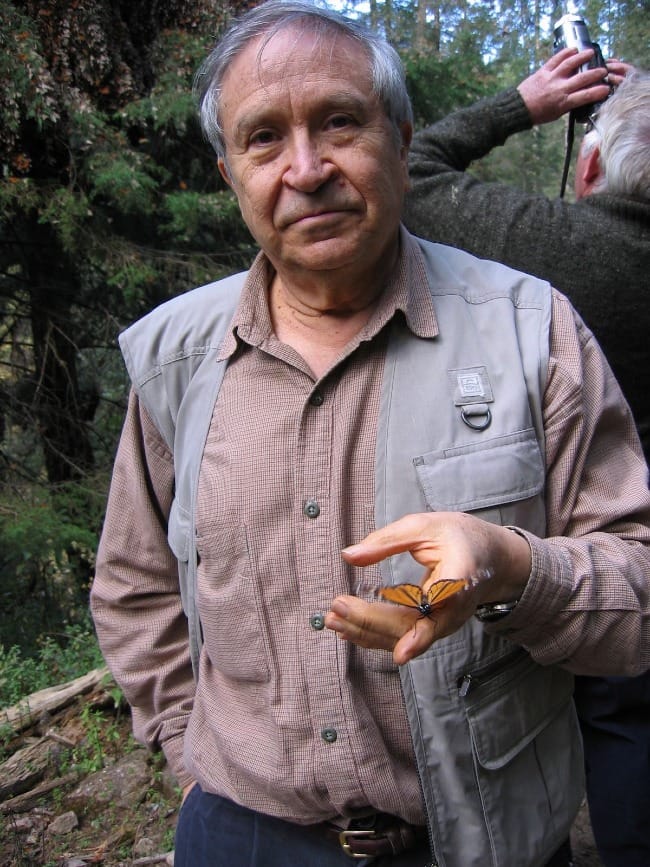

When Aridjis was growing up in Mexico, he lived near what is now the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. He remembers watching the butterflies “explode from the tree branches when the sun hit them.” It was here that two of his great passions were kindled into being: writing about creation and protecting that creation.

These passions have informed his life. In the short poem below, his permanent fascination with this particular creature—the monarch butterfly—is evident.

A una mariposa monarcha/To a monarch butterfly

by Homero Aridjis

Tu que vas por el día

como un tigre alado

quemándote en tu vuelo

dime qué vida sobrenatural

está pintada en tus alas

para que después de esta vida

pueda verte en mi noche

You who go through the day

like a winged tiger

burning as you fly

tell me what supernatural life

is painted on your wings

so that after this life

I may see you in my night

Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2001.Translation by George McWhorter

The regard present in this poem permeates his writing. As both a writer and an activist, his is a story of long and deep engagement in loving and caring for the world and all its creatures.

In 1985, Aridjis founded the Grupo de los Cien (Group of 100), an organization of writers (including Octavio Paz and Gabriel García Márquez), artists, and intellectuals whose goal was to protect the environment and biodiversity in Mexico and Latin America. As Aridjis has said, "Nature can live without us but we as human beings, we can’t live without nature."

The Group of 100 has worked for many environmental causes in the years since, but none closer to Aridjis’ heart than the work done on behalf of monarch butterflies. The poem below voices both the love and the anger that motivates Aridjis’ work.

About Angels IX

by Homero Aridjis

Through the night, coated in frost,

the woods around my town wait for the light of dawn.

Like closed leaves, the monarch butterflies

cover the trunks and branches of the trees.

Superimposed, one upon the other, like a single organism.

The sky goes blue with cold. The first rays of sun

touch the clusters of numb butterflies

and one bunch falls, opening into wings.

Another cluster is lit and through the effect of the light

splinters into a thousand flying bodies.

The eight o'clock sun opens up a secret that slept

perched on the trunks of the trees,

and there is a breeze of wings, rivers of butterflies in the air.

Visible through the bushes, the souls of the dead

can be felt with the eye and the hand.

It is noon. In the perfect silence, the sound

of a chainsaw is heard advancing toward us,

shearing wings and felling trees. Man, with his thousand

naked and hungry children, comes howling his need

and shoving fistfuls of butterflies into his mouth.

The angel says nothing.

Mexico City: Fundacion de cultura Televisa, 1994. Translated by George

McWhirter and Betty Ferber.

Through the work of the Group of 100, the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in Aridjis' home state came to be, though the designation didn't solve all the problems of chainsaws and destruction. When Aridjis later served as Mexico's ambassador to UNESCO (one of the many public posts and honors he has held and received), he was able to get the Biosphere designated as a UN World Heritage Site—another step in the right direction. Aridjis calls his work to save the monarch butterfly the most important environmental work of his life.

In 1997, Aridjis was elected to the first of his two terms as president of PEN International, an organization for writers dedicated to upholding the free exchange of ideas and promoting freedom of expression. Because of his environmental work, there was concern that his environmental activism and other experiences would affect the activities of PEN. In answer he said,

"When I was a child, I thought of trees as something permanent and stable. It was also a representation of serenity. Something different from the violent world of men. Then as I grew up, I saw man’s aggression against nature. That is how I decided to defend what I love; otherwise, all my poetry would be nothing but rhetoric. I would be talking about trees and rivers without becoming involved with them."

The love he speaks of is tangible both in his writing and in his environmental work; his passionate writing gains weight when you know the many other ways he has fought for the creatures he writes about.

Consider his poem, The Eye of the Whale.

The Eye of the Whale

By Homero Aridjis

‘And God created the great whales…’. Genesis, 1:21

For Betty

And there in San Ignacio Lagoon

God created the great whales

and each creature that moves

on the shadowy thighs of the waters.

God created dolphin and sea lion,

blue heron and green turtle,

white pelican, golden eagle

and double crested cormorant.

And God said unto the whales:

‘Be fruitful and multiply

in acts of love that are visible

on the surface

only through a bubble

or a fin, flapping,

while the cow is seized on the long

prehensile penis below;

there is no splendour greater than a grey

when the light turns it silver.

Its bottomless breath is

an exhalation.’

And God saw that love

between the whales

and the sporting with their calves

in the magical lagoon was good.

And God said:

‘Seven whales together

make up a procession.

One hundred, a daybreak.’

And the whales came up

to spot God over

the dancing gunnels of the waters

and God was sighted by a whale’s eye.

And whales filled

the waters of the earth.

And the evening and the morning

were the fifth day.

San Ignacio Lagoon,

1 March 1999

Copyright Homero Aridjis. Trans. George McWhirter. Eyes to See

Otherwise: Selected Poems. New York: New Directions Book, 2002.

With its descriptions of mating whales alongside God speaking words of joy and blessing over them, the poem brings together imaginative spirituality and down-to-earth physicality. The announcement that "God saw...that it was good" proclaims a beautiful, beloved, lively creation bursting out of Genesis 1:21—with the poem's images amplifying the biblical verse.

The affection and awe voiced in the poem are echoed in Aridjis' advocacy. In 1994, Mitsubishi and the Mexican government began plans to build the world's largest industrial salt factory in what was (and is) the last remaining undisturbed breeding and calving lagoon of the Pacific gray whale. Aridjis and the Group of 100 spearheaded a campaign against the plan, eventually drawing in 35 Mexican environmental groups and assistance from the Natural Resources Defense Council (“NRDC”), the International Fund for Animal Welfare (“IFAW”), and many international celebrities. In 2000, after six years of letters, newspaper ads, and protests, the Mexican president announced abandonment of the plans that had been considered a done deal.

Aridjis, his wife Betty Ferber, and his coworkers have achieved other significant environmental victories as well. These have included a permanent ban on the capture and commercialization of all seven species of sea turtles in Mexico, the daily monitoring of air quality in Mexico City, the phasing out of leaded gasoline, a reduction of lead in pottery, and the return of Chernobyl-contaminated powdered milk shipments back to its source before it could be distributed in Mexico.

This type of work in this part of the world is not always safe. Aridjis has received death threats and has needed to hire bodyguards at times. Last year, Mexico was labelled the world's deadliest spot for environmental activists, with 54 environmental and land rights activists killed in 2021, including two who were connected with the Monarch Reserve.

Despite these threats, Aridjis shows no sign of ending his activism. He has stated, "I believe that ... human beings bear a huge responsibility to all other species to preserve our planet's biological wealth."

Because Aridjis' work originates from a great love for this world and its creatures, I end with a poem that fluently expresses his love for “this ark of the living.” Let its love and beauty soak into you as you read this poem.

The Ark

by Homero Aridjis

There are birds who bear on their wings

the green of the leaf and the stone’s ochre

there are blue beasts flaunting in their stripes

shreds of halo or cloud where day still reigns

there are lions who scatter in their wake

claw-tracks like yellow ears of wheat

horses trembling in immobility

in a silence that seems to leap

fauna pricked to madness that has sprung

from the wheatfield the sun and autumn

a joy of shapes sounds and colours

swaying and clamouring in patches of light

a whole creation moving

playing in the splendor of animal purity

sailing harmoniously through the soul

of this ark of the living

Translated by Betty Ferber. New Directions Book, 2002.

Reflection Questions: How does your love for this world translate into concrete action? Are your actions and words consistent?

You can listen to Homero Aridjis read some of his poetry here. A book about his work may be purchased here. Spanish and English translations of many of works of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction may be found on Amazon.

Feel free to email me at info@circlewood.online or leave a comment below.

Louise