This column is adapted from a recent sermon. Your thoughts and questions are welcome - James

We are living in one of those moments in history when the world seems to be changing so quickly we cannot keep up – the climate is changing, cultures are changing, and the Church is changing. In many ways, these have been stabilizing forces, the solid ground that makes life possible and fills it with meaning and purpose. The ground is now shifting, leaving many of us feeling unsettled.

A biblical theme that echoes the unsettled nature of our current experience is exile, the forced expulsion of people from their native country. Reflecting on ancient Israel’s experience of exile through a letter the prophet Jeremiah sent to exiles in Babylon can help us understand and respond to our current experience of life on a changing planet and in a changing Church.

Weeping By the Water

In 586 BCE, the Babylonian empire destroyed Jerusalem, including the great temple that had stood for centuries at the heart of the city as a symbol of God’s ongoing presence and blessing. Many Israelites, including a large contingent of leaders, were taken from the ruined city to Babylon to live in exile. For a nation whose identity was inextricably bound to Jerusalem and the land of Israel, this was a physical, emotional, and spiritual catastrophe. Their world had crumbled alongside the walls of their beloved city. Psalm 137 captures the shattering grief of those in exile: “By the waters of Babylon we sat and wept as we remembered Zion.”

To this bewildered, dislocated, grief-stricken people, the prophet Jeremiah writes a letter that gives them three crucial instructions and a promise.

How to Live in Exile

The letter begins this way: “This is what the Lord Almighty, the God of Israel, says to all those I carried into exile from Jerusalem to Babylon.” (29:4)

These introductory lines indicate that God played a role in their exile alongside the Babylonian empire. It is a reminder that God’s promise of land to Israel was conditional on their commitment to live according to God’s laws so that the land would flourish and the nations would be blessed. They had not lived up to this calling, and have been “carried into exile” by God. The letter then moves to instructions for how they are to live in exile.

“Build houses and settle down; plant gardens and eat what they produce.” (29:5)

This command lets the exiles know that their stay in Babylon will not be brief. There will be no quick fix – Babylon is their new home, and they are going to be there for a while. This is an important word, because other prophets were giving the people a different message. A prophet named Hananiah had declared the following:

“This is what the Lord Almighty, the God of Israel, says: ‘I will break the yoke of the king of Babylon. Within two years I will bring back to this place all the articles of the Lord’s house that Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon removed from here and took to Babylon.” (28:2-3)

The temptation to give the people good news is understandable, but Jeremiah rebukes Hananiah and refuses to sugarcoat reality. He tells the people that the exile is going to last at least 70 years, meaning the majority of exiles will live out their remaining years in Babylon. But this does not mean that their lives are over, as the next instruction indicates.

“Marry and have sons and daughters; find wives for your sons and give your daughters in marriage, so that they too may have sons and daughters. Increase in number there; do not decrease.” (29:6)

The people are to keep living and investing in future generations, seeking marriages and welcoming children. They are to increase in numbers, which might be an intentional allusion to God’s command in Genesis to be fruitful and multiply – exile does not mean that God’s plan for creation, or Israel, has failed. The exiles have a future, even if, as we see in the next command, this future is currently bound up with the future of Babylon.

“Also, seek the peace and prosperity of the city to which I have carried you into exile. Pray to the Lord for it, because if it prospers, you too will prosper.” (29:7)

This is, perhaps, the hardest command. Not only do they have to live in the heart of the enemy’s empire, they are to work for its good. They to seek its peace (Hebrew “shalom”), its comprehensive well-being, for their own well-being is tied up with Babylon’s. But as hard as this is, the letter indicates that it will not last forever.

“I will gather you from all the nations and places where I have banished you,” declares the Lord, “and will bring you back to the place from which I carried you into exile.” (29:14)

Their exile will come to an end. There will be a return to the land, though it will not mean a return to the past. They will need to reimagine life in the land after exile.

Our Two Exiles

There are connections to be made to this ancient letter if we see that we are also living in exile – two exiles, actually. The first exile is a planetary exile of our own making. We have treated the earth like Nebuchadnezzar treated the nations around Babylon – raw material to be plundered and controlled for our own expansive desires.

The writer and educator David Orr frames the consequences of this approach in the language of exile.

“We are in the process of evicting ourselves from the only paradise humankind has ever known – what geologists call the Holocene. This 12,000-year age has been abnormally benign with a relatively stable and warm climate, more or less perfect for the emergence of Homo sapiens. But CO2 levels are now higher than they’ve been in hundreds of thousands of years and rising still higher each year. We are creating a different and more capricious and hostile planet than the one we’ve known for thousands of years.”

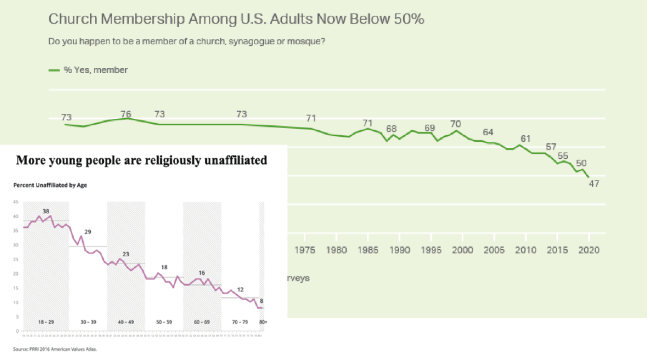

The second exile is particular to the Church. In the West, the Church is being exiled from its historic place in the center of cultural and civic life. Church affiliation has dropped precipitously, particularly among young people, while church closings and mergers have accelerated. Trust in institutional Christianity has declined alongside formal membership. Some of the reasons for this decline come from within. There seems to be a constant stream of stories about churches, and church leaders, becoming infatuated with power, making an idol out of numerical growth, ignoring internal systems of abuse, and neglecting the basic message of Jesus to worship God, seek justice, and serve the poor.

It the midst of these two exiles, it is tempting to listen to voices that sound like the prophet Hananiah. These are the voices that tell us climate change isn’t real, or that it is real but we shouldn’t be alarmed about it. These are the voices that promise a technological breakthrough which will singlehandedly return the earth to its former stability. These are the voices declaring that God wouldn't let anything drastic happen to us or the earth, or that we should celebrate the earth's destruction because it will hasten God’s return. These are voices telling us that young people leave the church, but come back when they have kids of their own. Like the exiles in Babylon, we need to ignore these voices and face reality. While no one can truly predict the future, there are no easy fixes to the dilemmas we face; a long journey lies ahead of us.

Exile as Opportunity

The good news is that times of exile can illuminate the mistakes of the past and begin to lay the groundwork for new ways of living and being to emerge. The cultural historian Thomas Berry saw the undoing of our industrial world as an opportunity for humanity to see the world differently.

“The greatest of human discoveries in the future will be the discovery of human intimacy with all those other modes of being that live with us on this planet, inspire our art and literature, reveal that numinous world whence all things come into being, and with which we exchange the very substance of life.”

The late writer and editor Phyllis Tickle saw the same opportunity in the current decline of Christianity.

“[A]bout every five hundred years the empowered structures of institutionalized Christianity, whatever they may be at the time, become an intolerable carapace that must be shattered in order that renewal and new growth may occur.”

New patterns and insights might emerge for humanity and the Church by following the ancient advice of Jeremiah. We can grieve what we have lost, and then settle into the new reality. We can begin to develop communities and churches that are resilient and organized around creative renewal. This will take conscious adaptation, imagination, and experimentation, though we could probably take Jeremiah’s advice to plant gardens literally.

We can also invest in the coming generations. In my experience, young adults are the most anxious about the future and the most active in movements to make things better. Many are suspicious about institutional religion, but continue seek spiritual connection, meaning, and purpose. We need to listen to their worries and ideas, join them in the work of renewal, and cultivate the kind of hope that is born in solidarity.

Finally, we can seek the peace of the places we live. We can ask what God is doing to bring shalom to our particular ecosystems, human communities, and churches. Where is there suffering? Where is there flourishing? Who is building shalom? How might we join them?

Life in exile is not easy. But I am comforted that when God “carried” the Israelites into exile, it was also an act of care and support. God carried them through the difficult journey and into an unknown future, and will carry us as well.

With you on the Way,

James