Here is the tenth installment of our Exodus series. If you want to take a minute to read Exodus 18, click HERE. And if you missed the last column in this series, click HERE. As always, we will walk through the text and highlight aspects that are not typically noticed, and then conclude with a few themes for ecological discipleship. Thoughts and comments are welcome. - James.

Family Reunion and Testimony Time

As Israel camps near Sinai, word about them has spread through the wilderness. Jethro, "priest of Midian and Moses' father-in-law," has heard the news of their escape from Egypt and has come to their encampment with Moses' wife, Zipporah, and their two children. The text does not say why Moses had sent his wife and children away, but it is likely that the threat posed by returning to Egypt was too great to bring them along. The family is now reunited, another signal that Egypt is behind them and a new community is forming.

Jethro and Moses go into a tent, where Moses "told his father-in-law all that the Lord had done to Pharaoh and to the Egyptians for Israel’s sake, all the hardship that had found them on the way, and how the Lord had delivered them." It is a simple retelling of the story, and I find it interesting that Moses takes no credit for what has happened - the focus is on God's just and liberating actions for an enslaved people. Jethro responds with joy, and confesses his new understanding that "the LORD is greater than all the gods" - another reference to the way the LORD defeated the gods of Egypt. It is a reminder that people of faith have stories to tell that people need to hear.

Establishing Community Justice

Jethro's time with Moses shifts from the past to the present, from the justice and liberation that God has provided to the justice and liberation that Israel's leaders must provide. Once again we see the connection between what God does and what God expects the people to do.

Jethro observes Moses struggle to adjudicate problems within the community as the sole judge. After watching a long line of people wait all day for their turn before Moses, he gives Moses a very straightforward assessment: “What you are doing is not good." In addition to pointing out that Moses may not be the most skilled administrator, Jethro's admonition is quite possibly an intentional reference to Genesis 1 - what Moses is attempting to do will not foster the kind of justice intended by God for the created order. Moses and the people will wear themselves out - definitely not a recipe for cultivating a Sabbath community! Additionally, Moses cannot and should not do it alone - he is neither God nor Pharaoh.

Jethro's solution is to distribute authority and provide protections for the people in the form of an appellate system of justice. Moses is to select men of integrity (a reality of the patriarchal system of the time that we should acknowledge and move beyond) to mediate justice for variously sized groups, with the understanding that cases which cannot be decided in the lower levels can be appealed up the chain all the way to Moses. This is a radical departure from Egypt, as it seeks to protect the rights of common people, especially those with little social power. In this way it anticipates the substance and heart of the Law that God is about to give to Moses on Sinai.

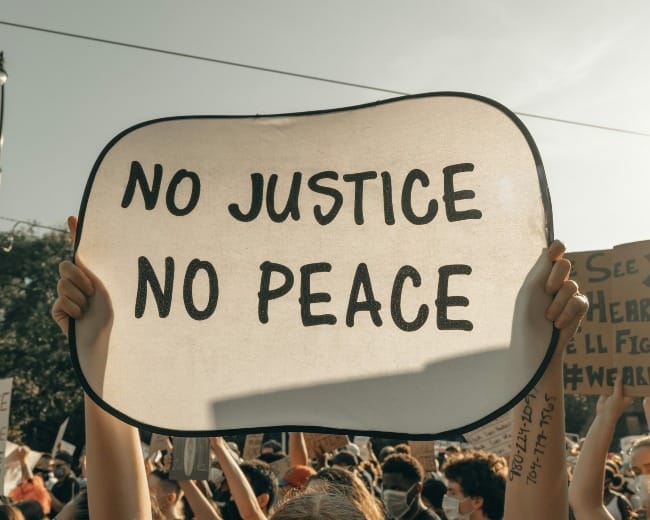

Jethro concludes his speech to Moses by saying, "If you do this and God so commands you, then you will be able to endure, and all these people will go to their homes in peace.” A righteous system of justice is a requisite for a community to be at peace (the Hebrew word here is shalom.)

Let me suggest two themes for us to reflect on as ecological disciples.

A Just Society is Part of a Just Creation

If we remember that human beings are part of creation, just societies are an integral part of a just creation. This means that seeking shalom as an ecological disciple requires addressing social injustice. We must care about racial and economic injustice and support the kind of cultural and legal frameworks that promote equality and protect the vulnerable. We should also note that, although consequences are a natural part of Old Testament law, the justice it seeks is more restorative in nature than retributive.

In addition, because human beings exercise tremendous power within ecosystems, bioregions, and the planet as a whole, how we organize and govern our societies directly impacts the ecological order. As we move into the chapters in Exodus dealing with the giving of the Law, we will see explicit examples of this.

Expanding Justice in An Ecological Age

As we move into the section of Exodus which focuses on the giving of the Law, it is important to remember that the Law is not static. It flexes, changes, and adapts to new situations, even within the biblical text. The heart of the Law, however, remains the same: worship and serve God; live with integrity; protect the vulnerable. This is captured so well by Jesus when he was responds to a question about the greatest commandment: "'You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets.”

In our age of ecological awareness and crisis, we must ask what it means to follow these commandments. In particular, we can learn from the way that Jesus expanded people's definition of neighbor. Applying that to our time, I think we must include our fellow creatures as neighbors. Following the counsel of our Indigenous friends, we must see and treat all created beings as kin. This is part of the thinking behind the Rights of Nature movement, which seeks legal protection for ecosystems, often identifying specific rivers or mountains as legal entities deserving specific rights. Whether you agree with this approach or not, we need to see that protecting the vulnerable includes all creatures struggling to survive and find peace in this world. We must pursue the kind of justice that restores people and places.

This is a big task, to be sure. But none of us are asked to do it all. Like Moses, we are neither God nor Pharaoh. Perhaps we are more like one of the people chosen to look after a group of ten, or 100, or 1000. Loving God and neighbor - being people of justice - starts with those closest to us, the people, landscapes, and creatures that make up our place.

What could you do, in your neighborhood, to help ensure that all God's creatures - human and non-human - "will go to their homes in peace?"

With you on the Way,

James

Leave a comment below, or email me directly at james.amadon@circlewood.online.

Like what you are reading? Consider a one-time gift to our parent ministry, Circlewood, or join our supporter community, The Circlewood Stand. Just $10/month makes a huge difference, and makes you part of a growing group of people standing FOR the good of creation and standing WITH Circlewood as we make a difference together. Thanks for considering!