Here is the fifth installment of our Exodus series. It covers quite a few chapters, so it is longer than usual. If you want to take a few minutes to read Exodus 7-12, click HERE. And if you missed the last column in this series, click HERE. Once again, we will walk through the text and highlight aspects that are not typically noticed, and then conclude with a few themes for ecological discipleship. Thoughts and comments are welcome. - James.

__________________________

A Brief Overview

These six chapters tell the story of the ten plagues God unleashes upon Egypt. The text refers to them as "signs," "wonders," and "acts of judgement," for they are meant to demonstrate and communicate God's sovereign control as lord of creation (which includes people, empires, etc.). The plagues also help accomplish God's plan to liberate the Hebrew slaves.

It is important to note, once again, that God is shown to be both creator and redeemer, and that these two divine identities/actions are always integrated and working in unity. We see this throughout the plague sequence. God works through Moses to demand that the Hebrew's be freed and mobilizes creation to enact judgment on Pharaoh for refusing. Let's look at how this plays out in each of the plagues.

Turning the Nile to Blood

Whoever controls water, controls life. God strikes first at the very lifeblood of the Egyptian empire, turning the source of Egypt's life and economy into a cesspool of death. Note that this plague lasts seven days - it is a reversal of the original creation story, in which the waters of chaos are tamed and fill up with life. God is giving Pharaoh direct evidence of who is really in control of creation, as well as enough time to change his mind and avoid escalating the conflict. Despite the dramatic opening act and 7-day waiting period, Pharaoh sees that his sorcerers can perform the same sign and refuses to let the people go.

Filling the Land with Frogs

The next plague fills the land with frogs. It reminds us of God's command from Genesis that the water "teem with living creatures." It is an example of the fullness of creation, but out of balance, overwhelming humans and causing widespread chaos. Pharaoh's sorcerers are able to replicate this sign as well, but he is clearly shaken. He asks Moses to intercede with God so that the frogs will depart, and promises to let the people go. Moses prays, God relents, and Pharaoh reneges. As I wrote in my last column, entrenched power does not let go easily.

Nasty Gnats

To enact this wonder, Moses strikes the dust with his staff. The dust might be an allusion to God's control over life and death - the first humans are created out of dust/soil, and the poetic description of the fallout from Adam and Eve's transgression ends with the following: "for dust you are and to dust you will return." I imagine the swarm of gnats must have looked and felt (and tasted!) like living dust storms. This time, Pharaoh's magic men cannot reproduce the feat, and in a moment of clarity they declare, "This is the finger of God." Despite this, Pharaoh's resistance persists.

Full of Flies

The swarms of flies that follow the gnats are clearly an escalation by God. They "pour" into Pharaoh's palace, and "throughout Egypt the land was ruined." God spares the land of Goshen, where "my people live." Now the battle lines are drawn, and there is serious ecological and economic damage. Pharaoh knows he cannot remain openly recalcitrant, so he turns to negotiation: "Go, sacrifice to your God here in the land." This undermines the central purpose of the proposed exodus - the physical relocation of the people to a place not controlled by Pharaoh. This is at the heart of Moses' request, so he wisely refuses. Pharaoh gives in a little more - "you must not go very far" - but ends up rescinding the offer entirely. Hearts soften slowly, and empires die hard.

Livestock Struck

First Pharaoh's source of water was compromised, then his land ruined, and now his domesticated animals are killed. I wish these innocent animals were not caught up in the drama in this way (and the innocent firstborn children a bit later), but there is a sense that God is giving Pharaoh chance after chance to prevent further escalation, and would prefer to bless Egypt. In any case, this is another direct strike on the Egyptian economy, yet Pharaoh remains unmoved.

A Breakout of Boils

We now see human bodies directly affected, with festering boils that are clearly and painfully debilitating. It is a clear demonstration that Pharaoh cannot control his people's health and well-being - even human bodies are at the mercy of the LORD. Pitiful and miserable as it must have been, Pharaoh's heart remains hard.

Hail to the Chief

The assault continues. A "once-a-millennium" hailstorm destroys anything left outside - trees, crops, animals, people. It is a blow to the heart of the empire - a national emergency that could bring famine to a nation that prided itself on being a regional breadbasket. Power and glory tend to disappear quickly when one's people have nothing to eat. Pharaoh seems to come to his sense, but again reverses course once the hail stops.

Locusts Leave Nothing Behind

The hail is followed by locust swarms that cover the ground completely and devour what is left of the storm-damaged crops. The regime is starting to crumble. Pharaoh's officials try to speak sense into their leader: "Let the people go, so that they may worship the LORD their God. Do you not yet realize that Egypt is ruined?" You would think at this point that Pharaoh would cut his losses, let the people go, and try to rebuild the country with whatever shred of power and dignity he had left. Nope - Pharaoh is the kind of person that would rather lose everything than admit he was wrong.

Deep Darkness

The three days of darkness God visits on Egypt (but not Goshen) echoes the primordial darkness in Genesis before God declares "Let there be light." This is the darkness of chaos and death, "darkness that can be felt." God is enacting a reversal of creation in the land that reveals the blindness of Pharaoh and the Egyptian regime. The enlightened empire now wallows in darkness, their land in ruins, their leader unable to stop the destruction. Yet Pharaoh's heart hardens even more, and he throws Moses out of his presence, not knowing that he has just performed a symbolic act of exodus that foreshadows what is to come - though it will come at a terrible cost to the king and his people.

Firstborn

God has chosen despised, downtrodden slaves to be his chosen people - and has referred to them collectively as "my firstborn son" (4:22). In a final, terrible act of judgment, God strikes down all the firstborn children of Egypt. The cries of oppression that spurred God to action are now echoed by cries of pain and loss by Egyptian parents. Pharaoh's regime is finally brought to his knees, and he now commands Moses and the Hebrews to leave.

There is a lot in these chapters - here are a few themes for our journey of ecological discipleship.

The Perpetual Quest for Control of Creation

Pharaoh's belief that he could bend creation to his will with impunity is perpetuated throughout history. Our modern, technological era has taken this to new heights - we have tried to become, in the words of philosopher Rene Descartes, "lords and masters of nature." We have set ourselves up like gods, seeking to create a world that serves us. And when problems arise, we turn, like Pharaoh, to our technological sorcerers for solutions. We see this in the American West, where decades of rampant water use is draining rivers and reservoirs to historically low levels. The thirst for cheap food through industrial agriculture, combined with climate change and a prolonged drought, has put 40 million people at risk. Potential solutions abound, but few of them address the systemic and cultural changes needed to consume far less water than we currently do.

One of the messages of Exodus is that those who seek absolute power and control will not find it - eventually creation rises up in response - whether in the form of human liberation movements or the response of stressed natural systems.

God poses a question to Pharaoh that we need to hear today: "How long will you refuse to humble yourself before me?" Which brings me to our second theme.

The Importance of Acknowledging the Creator

We rightly emphasize that God's actions in Exodus are about freeing the Hebrews. But they also about getting Pharaoh, and Egypt, to recognize and acknowledge God as creator. We see this in these key verses from Chapter Nine:

"But this is why I have let you live: to show you my power and to make my name resound through all the earth."

"I will stretch out my hands to the Lord; the thunder will cease, and there will be no more hail, so that you may know that the earth is the Lord’s."

This may seem almost petty to us, as if God is desperate for the adulation and worship of Egypt, but I think it is more about restoring Egypt to their rightful place within the order of creation.

Acknowledging the Creator forces us to remember we are creatures. It de-thrones us when we set ourselves above other humans and/or our fellow creatures. It de-centers us when we make ourselves the locus point of existence and meaning. It also makes ethical demands on us, for the Creator is clearly on the side of the poor and oppressed.

Plagues and Planetary Boundaries

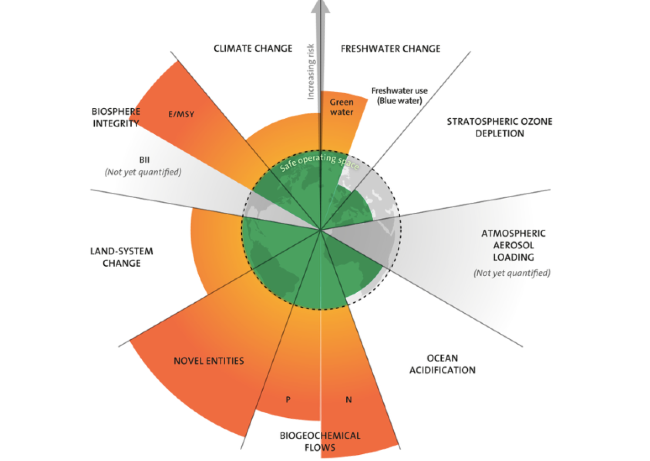

The ten plagues are interesting to me in light of the nine planetary boundaries identified by researchers at Stockholm University. These are quantitative planetary boundaries within which humanity can continue to develop and thrive for generations to come. They measure what is happening to the air, land, and water, particularly the large-scale impact that harmful chemicals, overconsumption, and physical changes to the land are causing (you can see the nine areas in the chart above). Crossing these boundaries increases the risk of generating large-scale abrupt or irreversible environmental changes. According to their research, we are already crossing six of the nine boundaries.

The comparison is limited. These are not plagues set upon us by the hand of God - we are the cause. But there are connection points: the Pharoah-like hubris of manipulating creation in the service of empire building; the oppression of humans, our fellow creatures, and the land in service of economic growth; the warnings (with scientists in the role of prophets) of escalating consequences if we do not change our behavior; and the slow response of those in power (and the public at large) to make those changes.

Final Thoughts

I believe we need a new exodus, one that does not take us to a new promised land but roots us more firmly and justly right where we are. For those who live within modern-day empires, as I do, this will require humility, courage, and sacrifice - three things Pharaoh could not bring himself to embrace. Can we?

With you on the Way,

James

I love to hear from you - feel free to leave a comment or email me directly at james.amadon@circlewood.online.

Like what you are reading? Consider joining our supporter community, The Circlewood Stand. Just $10/month makes a huge difference, and makes you part of a growing group of people standing FOR the good of creation and standing WITH Circlewood as we make a difference together. Thanks for considering!