There is a church near where I live that is named after a major freeway. The founding members chose a place for the congregation to gather just off a strategic exit so that people could easily drive to church on Sundays from as far away as possible. The worship and sermons are geared toward learning biblical and spiritual principles that, for the most part, are broadly aimed at an individual’s spiritual development and evangelistic practice. They list no commitments to the social or ecological needs and issues of their area.

I am sure that the people are kind, the leaders well-intentioned, and that they do meaningful things together, but there is nothing (except the highway) that connects this church to its particular place. The church could be located anywhere, named for whatever highway provides the most convenient off-ramp. This type of church is common, especially in North America, and is producing generic, placeless followers of Jesus.

This is a problem because the Bible's big story of creation-to-new-creation, which I wrote about in "Shift #2: A Bigger Gospel," has universal meaning precisely because it tells the story of specific people in specific places. The landscapes in which these stories take place - Eden, Egypt, Israel, Corinth, etc. - are part of the story, woven into God's plan to bring healing and redemption to the whole world. Jesus did not come to earth as an idea, but as a first-century Palestinian Jew on the edges of the Roman Empire. And this is how God still works; we learn, grow, and serve by seeking God's presence where we are, loving the unique neighbors we've been given, and caring for the unique corner of creation we've been entrusted with. This is no easy task. The writer Scott Russell Sanders describes his journey this way:

It has taken me half a lifetime of searching to realize that the likeliest path to the ultimate ground leads through my local ground. I mean the land itself, with its creeks and rivers, its weather, seasons, stone outcroppings, and all the plants and animals that share it. I cannot have a spiritual center without having a geographical one; I cannot live a grounded life without being grounded in a place.

How do we shift our discipleship to a more place-based, localized expression of faith. How do we answer the question, "What does it mean to follow Jesus in this place?"

What is This Place?: Discovering Your Bioregion, Ecoregion, and Niche

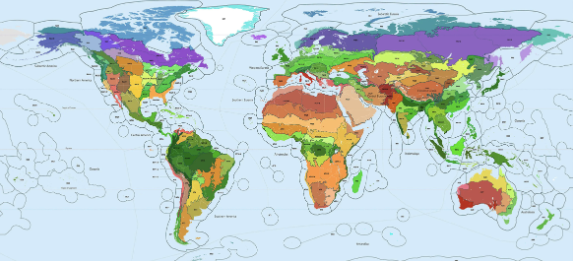

Most people talk about where they live in political terms – their country, state, province, city, and town. Many people can name their area’s basic geographical features – major landforms and bodies of water, some of the flora and fauna, and the basic makeup of human communities. Place-based disciples go deeper; we are interested in the specific earth-based features that define a place’s border and boundaries, and seek to know as much we can about what is happening within those borders. This localized knowledge often starts through understanding the bioregions we live in, and our place within them.

Imagine a map that defines areas of the earth based on unique geographical features, ecological systems, and human communities. It might look something like this rendering of the earth’s major bioregions.

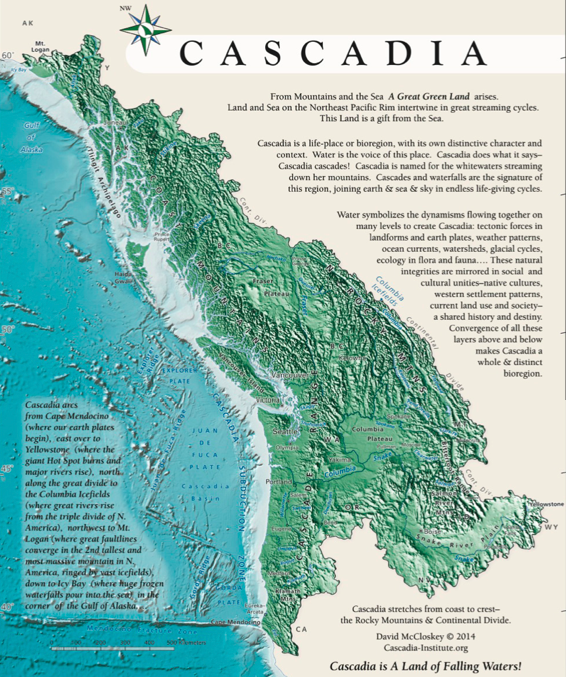

Bioregions are large areas that contain a defined ecological system which supports a unique community of plants and animals (think of the Amazon rainforest or the Alaskan tundra). I live in the bioregion often called "Cascadia" (also known as the Pacific Northwest Coastal Forests bioregion), which stretches from the Santa Cruz Mountains in central California to Graham Island in coastal British Columbia (People place the borders a little differently, but the map below is common). The region is defined by its forests, mountain ranges, connection to the Pacific Ocean, and a strong environmental ethic.

Within each bioregion are multiple ecoregions, which are unique ecological areas within the larger whole. My ecoregion is called Puget Lowland Forests, and is comprised of the area around Puget Sound that extends south to the Willamette Valley, east to the Cascade Mountain foothills, west to the Olympic Mountain foothills, and north to the east coast of Vancouver Island. It is a temperate, fertile region that can support massive forests, extensive prairies, an abundance of wildlife, and a large number of humans. Just how many humans the region can support is an open question; millions of people live in Cascadia, with more coming every day (I moved here 17 years ago). While the region has a strong environmental ethic, humans have significantly altered and degraded the region over the last 200 years.

Within each ecoregion are smaller ecosystems that have their own integrity within the whole. I live on Camano Island, where the organization I lead, Circlewood, cares for 40 acres of forestland. (If you want to see how we care for the forest and the learning center we plan to develop, check out the vision HERE.)

Camano Island is in Possession Sound, a small section of Puget Sound. It is accessible by car and is approximately 95 square miles. It was originally called Kal-lut-chin (“land jutting into the bay”) by the Kikialos and Snohomish, two of the tribes that fished and foraged around the island for centuries. Kallutchin was covered with old-growth forest until European explorers and settlers came through and extensive logging began. Today, the island is home to 13,000 permanent residents and swells to 17,000 in the summer months. Development pressure exists, which is one reason why Circlewood is seeking to model ways to inhabit the land that not only preserves, but enhances, the health of the forest.

Bioregional Discipleship

If you want to learn about your bioregion, go to www.oneearth.org/bioregions/. Pursuing this kind of ecological education is ultimately about understanding the particular corner of creation we call home and what it means to follow Jesus there. Matthew Humphreys, an Anglican priest and writer, calls this “bioregional discipleship.”

It is my conviction that rediscovering the ground as our common ground is crucial to discipleship today. This could begin in a community garden, a riverside cleanup, a march to save the wetlands, or a protest against a pipeline. It will undoubtedly require listening to the indigenous peoples who have inhabited our land as well as standing alongside them in efforts to care for it presently. If the bioregionalist authors are correct, as I suspect they are, we must confess we cannot care for the planet. Yet by joining together with our families, neighbors, churches, and communities, we can effectively begin to care for all of our places right now.

One way to put this local focus into practice is to identify and care for your watershed, the area of land within which all living things are linked to a common water source. Watersheds are as large as continents, and as small as your backyard. Author and activist Ched Myers calls this approach “Watershed Discipleship,” and invites us to see an intentional triple entendre in the term:

- Recognizing we live in a watershed moment of ecological crisis.

- Learning to be disciples in our watersheds.

- Developing awareness of the ways our watersheds act as our rabbis (teachers), pointing us to God.

Identifying and learning about the local creek, pond, river, lake, or ocean that makes your life, and the life of those around you, possible is a great way to further your understanding of the interconnectedness of creation as a whole and the particular dynamics and needs of your place.

Bioregional discipleship can be practiced whether you live in a city, a suburb, a rural town, or a wilderness area. No matter what place you call home, you can localize your devotional practices. When you pray, bring the specific people, animals, plants, and ecosystems of your place before God. Try walking prayer, which is simply inviting God to help you pay attention to what your senses experience as you move through your ecosystem.

You can take the Bible outside as well; it may help you notice just how much of Scripture takes place outside; on mountains, around lakes and rivers, within fields and pastures, in village courtyards and temple courts. Such reading can help us imagine what God might be doing in our places.

You can also bring the outside, inside. Artistic works that represent your bioregion can be placed on the walls of your home and church. Fresh, local flowers can grace Sunday worship. Locally baked bread can help us remember that communion connects us to God, one another, and the community of creation. The key is to embrace your place.

What does it mean for you to follow Jesus in your place? I'd love to hear your thoughts and questions. You can always reach me at james.amadon@circlewood.online.

With you on the Way,

James