In 1942, when Japanese Americans were removed from the West Coast of the United States to internment camps inland, the new environs were harsh and barren, intentionally isolated and surrounded by barbed wire. Growing green things was a way to grow hope in a desolate time and place.

The camps had been conceived of and constructed quickly after President Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066 of February 19, 1942 gave the Secretary of War authorization “to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded.” Beginning with the first Civilian Exclusion Order dated March 24th, which required all 54 Japanese American families living on Bainbridge Island in Puget Sound, Washington, to vacate their homes and report to the Puyallup Assembly Center by March 30, the Executive Order was soon applied to the entire Japanese American population of 120,000 on the West Coast. Citizenship wasn't a consideration, nor was anything else—except Japanese ancestry. Like the first 54 families, those who later received these orders were given as little as a week to leave everything behind except what they could carry.

This chain of events happened quickly enough that the "relocation centers" weren't even completed, which meant many thousands of uprooted people were sent to live in “assembly centers," until the structures were "completed." Most assembly centers were large fairground or racetracks; at the racetracks, the stables were merely cleaned out and labelled "living quarters."

In spite of the trauma of being torn away from homes, communities, and most of what they possessed, out of necessity and ingenuity, these displaced Japanese Americans built furniture, made privacy walls to separate family groups, and in a myriad of other ways worked to turn unfinished military installations into something more like home. They creatively used salvaged wood left from construction as well as whatever else they could repurpose and make useful items from. In addition to the eminently practical, they also quickly started art classes (many professional artists were interned in the camps) and created decorative crafts, using materials either discarded by builders or materials indigenous to the area. Each of the 10 camps had its own resources: Pleistocene shells at Tule Lake, California and Topaz, Utah, ironwood, cacti, and mesquite at Gila and Poston, Arizona, and hardwood at Rohwer and Jerome, Arkansas. The artistry and beauty of the objects created from found resources is impressive.

I think it significant that one of the first things the Japanese Americans did, even in the short-term assembly centers, was to plant gardens outside of the stall housing to grow familiar vegetables for their families and communities.

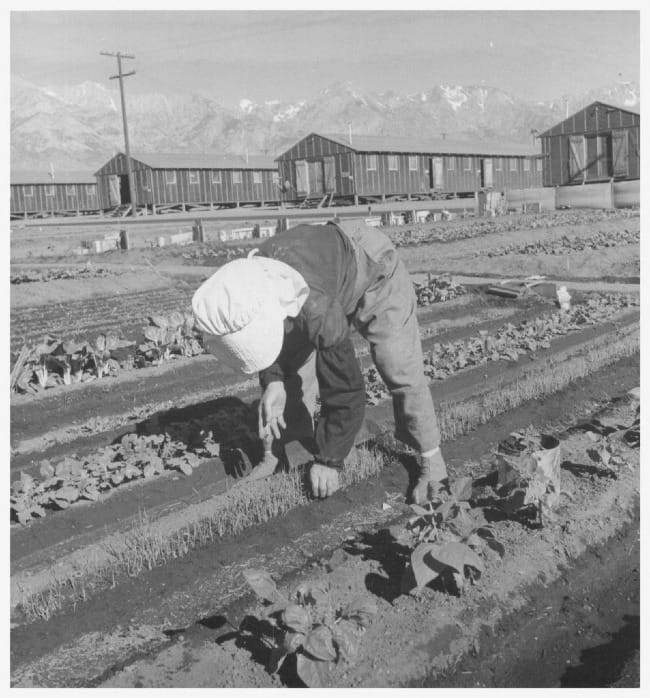

In all the camps, residents planted gardens, both large-scale food-producing gardens and orchards, and decorative gardens, spots to find refuge from the heat, dust, and bleakness.

"There was a constant battle with the powdery alkaline dirt that lay exposed on the ground after camp construction had removed all vegetation. There was no protection, even within the barracks, from the dust storms that engulfed the camp.” [1]

The orchards and large-scale gardens provided needed and welcome food for the camps, but the "pleasure gardens" and small household gardens seem to have provided something different—a reminder of identity. In the early 1940's, many Japanese Americans living on the West Coast worked in agriculture and made up a large majority of the landscape business in some cities, so the gardens were both a source of enjoyment and a connection to their history. In the spring of 1942, the first camp, Manzanar, was constructed. By June, Nikkei (second generation Japanese Americans) were developing ornamental gardens with ponds, foraged boulders, transplanted Joshua trees, and constructed landscape features.

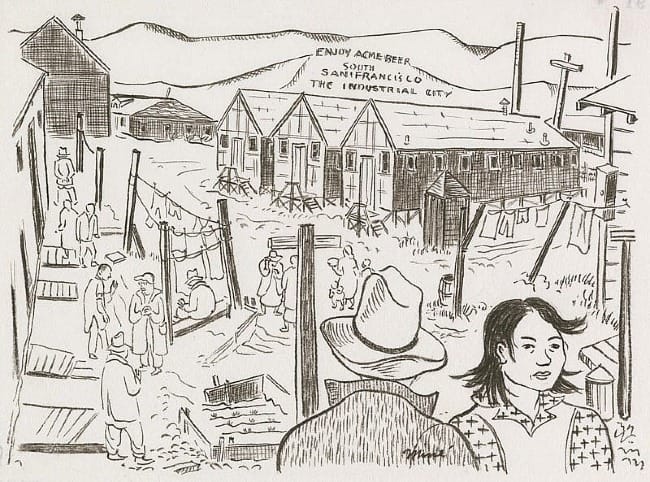

In paintings from the internment camps, I have noticed a trend. The bleakest of these paintings portray the dirt and dust—browns, grays—absent of natural growth.

The paintings that hold at least a sprig of hope often have something green growing in them—flowers, grass, trees (even scraggly ones) and often seem to be set in spring rather than winter.

All the camps had decorative gardens, and large-scale gardens and parks were built at some, including Manzanar, CA and Minidoka, ID. Manzanar's Merritt Park was the largest and most sophisticated of these. Kuichiro Nishi, a rose nursery owner from the San Fernando Valley, led its construction, creating enormous waterfalls, ponds, boulders, a tea house, and elaborate plantings.

Another large-scale garden, built at the entrance to Minidoka, was designed by Fujitaro Kubota, a nursery owner in Seattle. Other gardens were spread throughout the camps, such as the one pictured below, which featured a one-ton lava tube, named "Stove-pipe Rock," which was carted in from the sagebrush by the garden designer and his two sons.

A quote from Arthur Ogami, a 23-year-old in the camp, gives insight into the importance of these gardens to those who lived in the camps, “I think the gardens express that just because we’re here, we have to do something to refresh our feelings. I think that the garden is something that they want to express that there is hope for peace and freedom. And you can go to these gardens and feel it.”[2]

The gardens and parks were often the only greenery visible from inside the barbed wire fence. As one Minidoka internee stated, "When we first arrived here we almost cried, and thought that this is the land God had forgotten. The vast expanse of nothing but sagebrush and dust, a landscape so alien to our eyes, and a desolate, woe-begone feeling of being so far removed from home and fireside bogged us down mentally, as well as physically." [3]

I cannot imagine the mental and spiritual strength it took to not despair in this situation. It brings to mind Psalm 63:1 for me, where David writes, "You, God, are my God, earnestly I seek you; I thirst for you, my whole being longs for you, in a dry and parched land where there is no water." David's experience in the desert of Judah when he is fleeing from Absalom has parallels to the Japanese American internment experience—betrayal, danger, isolation, injustice, enmity.

There are so many important lessons that we, as a nation, need to learn from this time of our country's history, lessons to learn and remember so that we don't participate in or allow this kind of injustice in our future. But these big, historical lessons are beyond the scope of this post. The scope of this post is this: that the internees crafted places of growing things as one of their defenses against despair is significant to me.

It brings to mind the last couple of years, when so many people took up gardening that canning lids were almost impossible to find. I think there is an intrinsic need in people to connect with and make a home of the place where they live and, especially in times of disorientation and displacement, digging our hands in dirt and planting something and then watching it grow can help orient and place us. Disconnection is unhealthy and nurturing connection makes us healthier. In the horrible circumstances of 1942-1945 this was true, which makes me think it is true for us today as well.

Reflection Question: In hard circumstances, are there places that help you connect to hope? Are there specific practices that have helped orient and place you over the past couple of years?

Louise

Feel free to contact me directly at info@circlewood.online

[1] Hill, Kimi Kodani. Topaz Moon: Art of the Internment. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2000.

[2] Goto, Seiko. The Purpose and Role of Japanese Gardens in American Internment Camps. https://najga.org.

[3] http://www.minidoka.org/history-world-war-two-internment