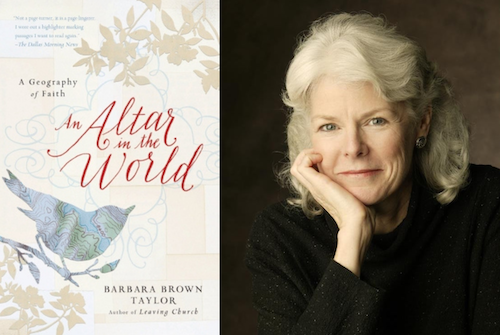

This is the third in a short series in which I am sharing pieces of prose that have significantly shaped how I see the natural world and my relationship to it. An Altar in the World by Barbara Brown Taylor is one of those books, for it reminds me how much I miss when I merely pass through this world without being attentive and present within it.

This book is best read at a pace the author advocates for in her book—slowly. Using personal experiences, biblical stories, and many other illustrations, she leads the reader through "practices" that celebrate the conjunction of the physical and the spiritual, pointing to God’s presence and holiness within that conjunction. (If you observe Lent, this book would be a refreshing and challenging book to lead you into some traditional and not-so-traditional Lenten spiritual practices). As Taylor asserts, “In a world where faith is often construed as a way of thinking, bodily practices remind the willing that faith is a way of life.” (An Altar in the World, © Barbara Brown Taylor, 2009).

Practicing with Our Bodies

The book looks at a total of twelve bodily practices: "The Practice of Waking Up to God," "The Practice of Paying Attention," "The Practice of Wearing Skin," "The Practice of Walking on the Earth," "The Practice of Getting Lost," "The Practice of Encountering Others," "The Practice of Living with Purpose," "The Practice of Saying No," "The Practice of Carrying Water," "The Practice of Feeling Pain," "The Practice of Being Present to God," and "The Practice of Pronouncing Blessings." Although this piece only looks at a couple of the practices she mentions in the book, I encourage you to find the book and explore all twelve. Within those practices are specific idea for small actions that can help us remember our body's connection to God and faith. As Taylor says in this book, our body's movements and actions can help us find our way into new realities, leading the way for our spirit to follow.

The body is a great focuser, whether the means is pain or pleasure. The body is a great reminder of where we came from and where we are going, on the one sacred journey that we all make whether we mean to or not.

Our bodies directly connect us with the reality of the earth. We can sit and theorize and think about the earth all we want, but it becomes real to us when we see it, touch it, listen to it, taste it, and smell it with our bodies.

In a world of too much information about almost everything, bodily practices can provide great relief. To make bread or love, to dig in the earth, to feed an animal or cook for a stranger—these activities require no extensive commentary, no lucid theology. All they require is someone willing to bend, reach, chop, stir. Most of these tasks are so full of pleasure that there is no need to complicate things by calling them holy. And yet these are the same activities that change lives, sometimes all at once and sometimes more slowly, the way dripping water changes stone. In a world where faith is often construed as a way of thinking, bodily practices remind the willing that faith is a way of life.

In the introduction of the book, Taylor states that the treasure we seek requires no lengthy expedition, no expensive equipment, no superior aptitude or special company. All we lack is the willingness to imagine that we already have everything we need. The only thing missing is our consent to be where we are. As creatures with bodies, consenting to be where we are is largely done with those bodies.

Waking Up to God

In the first chapter, “The Practice of Waking up to God,” Taylor relates an experience in Hawaii where in a “salty, fragrant church,” she re-learns that God is not confined to the walled structures that we call churches—the place many of us think we must go to in order to meet God. (As an Episcopal priest who has spent much of her life inside of churches, Taylor thoroughly understands this impulse). However, if, in fact, the whole world is the House of God, there are many choirs, many altars where God can be met—in fact, wherever we go, those altars surround us.

Taylor recalls Bible stories in which people encounter God under shady oak trees, on riverbanks, at the tops of mountains, and in long stretches of barren wilderness. God shows up in whirlwinds, starry skies, burning bushes, and perfect stranger .

We cannot confine God to church buildings, though we can ignore God’s presence elsewhere if we choose to. When we do recognize God's presence throughout the world, it brings a freedom with it, for it opens up the possibility of encountering God on any day of the week in whatever place on this earth we happen to be at that particular moment.

I do not have to choose between the Sermon on the Mount and the magnolia trees. God can come to me by a still pool on the big island of Hawaii as well as at the altar of the Washington National Cathedral. The House of God stretches from one corner of the universe to the other. Sea monsters and ostriches live in it, along with people who pray in languages I do not speak, whose names I will never know.

Practicing or not practicing this truth makes a huge difference in our experience. “Wise people do not have to be certain what they believe before they act. They are free to act, trusting that the practice itself will teach them what they need to know.”

Practicing the discipline of "waking up to God" means looking at the time and place where we are, and the people and other creatures around us with an openness to the possibility that this, in fact, might be where God is currently meeting us, rather than looking past them to a future time and place that we consider "the" place and time where God will show up.

… I can set a little altar, in the world or in my heart. I can stop what I am doing long enough to see where I am, who I am there with, and how awesome the place is. I can flag one more gate to heaven—one more patch of ordinary earth with ladder marks on it –where the divine traffic is heavy when I notice it and even when I do not. I can see it for once, instead of walking right past it, maybe even setting a stone or saying a blessing before I move on to wherever I am due next.

I love the way Taylor differentiates between the ways humans separates things into distinct piles, while God steps from one to the other without the same differentiation. It comes down to the divisions we make: Human beings may separate things into as many piles as we wish—separating spirit from flesh, sacred from secular, church from world. But we should not be surprised when God does not recognize the distinctions we make between the two. Earth is so thick with divine possibility that it is a wonder we can walk anywhere without cracking our shins on altars.

Paying Attention

In her chapter, “The Practice of Paying Attention,” Taylor talks about reverence—reverence that takes all kinds of forms, depending on what it is that awakens awe in you by reminding you of your true size. We cannot manufacture those moments of awe, but we can be ready to respond if one comes to us. Readiness and an attitude of welcome are important. By "reverence," Taylor refers to noticing and honoring holy moments when they are given to us. The opposite is to belittle, ignore, or walk past them, hurrying on to wherever our appointment calendar says we need to be.

As she says in the book, to maintain this type of open posture and awareness requires time and practice. The practice of paying attention really does take time. Most of us move so quickly that our surroundings become no more than the blurred scenery we fly past on our way to somewhere else…Reverence requires a certain pace. It requires a willingness to take detours, even side trips, which are not part of the original plan.

We tend to value the ability to multitask, which often means that our body is doing one thing while our mind is doing another—not really a stance that feeds reverence. Eating while we're reading or watching tv means we don't pay much attention to the food we're eating. Listening to something on earphones while we're walking on a path indicates a devaluing of the creation we are walking through. Planning our afternoon while someone is talking to us is not a sign of reverence toward that person. There may be good reasons for us to hurry to wherever we are going, but we are likely overlooking where we are right now when most of our attention is diverted to something and somewhere else. One thing I plan to practice this Lent (from my re-reading of this book) is eating breakfast without doing anything else at the same time—not reading, not working on the computer, not texting. Just eating my bagel, drinking my cup of coffee, and taking notice of what I am doing and appreciating the experience of my body enjoying and deriving nourishment from the food I am eating.

The practice of paying attention is as simple as looking twice at people and things you might as easily ignore. To see takes time, like having a friend takes time. It is as simple as turning off the television to learn the song of a single bird. Why should anyone do such things? I cannot imagine—unless one is wary of crossing days off the calendar with no sense of what makes the last day different from the next.

I would love to hear your thoughts on this book and, if you adopt one of the practices out of it for Lent, I would love to hear about that as well.

You can find out more about Barbara Brown Taylor and her writing on her website.

Louise

Feel free to leave a comment below or contact me directly at louise.conner@circlewood.online.

Want to learn more?

Find out more or support our parent organization by clicking below.