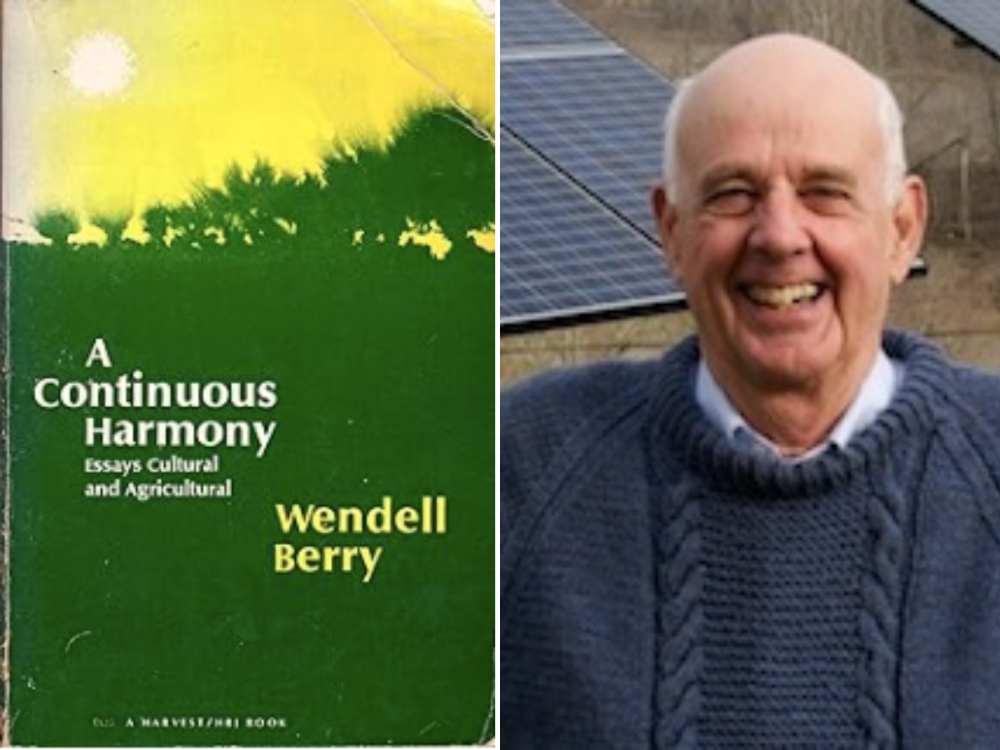

This is the second in a short series in which I am sharing pieces of prose that have significantly shaped how I see the natural world and my relationship to it. In this post, I look at A Continuous Harmony, a book of essays by Wendell Berry. Berry is a farmer, thinker, poet, novelist, and essayist who has long been a favorite writer of mine. (In fact, my very post written for The Ecological Disciple nearly three years ago, was on his poem The Peace of Wild Things).

Berry eloquently and consistently points out the destructive results of an American society that separates physical from spiritual, idea from practice, humans from the rest of creation, and integrity from work. In all his writing, he advocates for a view of other people, other creatures, and the land itself that is based in cooperation and community rather than competition and individual ambition. He sees and speaks as a farmer with a deep respect for the land and those who care for it. He points out the incalculable damage we are doing to the land, our communities, and ourselves because of both bad thinking and bad practice and exhorts us to change those patterns.

Efficiency vs. Quality

One of the way he challenges current thinking is in the view of efficiency. In measuring efficiency against quality, Berry will always side with quality. In fact, he disputes the current interpretation of efficiency—which typically means getting something done in the least amount of time with the least amount of effort and cost. As he points out, if the result is denigrated land or people, a product that does not last long (often by design) this is extremely inefficient, even if the financial cost is minimal. Real efficiency is great when something of quality, that holds is value and will last a long time, is created.

The standard of efficiency displaces and destroys the standards of quality because, by definition, it cannot even consider them. Instead of asking a man what he can do well, it asks him what he can do fast and cheap. Instead of asking the farmer to practice the best husbandry, to be a good steward and trustee of his land and his art, it puts irresistible pressures on him to produce more and more food and fiber more and more cheaply, thereby destroying the health of the land, the best traditions of husbandry, and the farm population itself. And so when we examine the principle of efficiency as we now practice it, we see that it is not really efficient at all. As we use the word, efficiency means no such thing, or it means short-term or temporary efficiency, which is a contradiction in terms. It means cheapness at any price. It means hurrying to nowhere. It means the profligate waste of humanity and of nature … Real efficiency is something entirely different. It is neither cheap (in terms of skill and labor) nor fast. Real efficiency is long-term efficiency. It is to be found in means that are in keeping with and preserving of the ends, in methods of production that preserve the sources of production, in workmanship that is durable and of high quality. In this age of consumerism, planned obsolescence, frivolous horsepower and surplus manpower, those salesmen and politicians who talk about efficiency are talking in reality about spiritual and biological death. (from A Continuous Harmony, © Wendell Berry)

When I first read Berry, I was a college student just learning the pleasure of having spending money. In that fresh excitement, I gravitated toward cheap, plastic items I could afford. Reading Berry recalled me from that thoughtless "freedom." The durable, handmade items I had grown up with (and was enthusiastically leaving behind), took on new value as I saw them in light of lasting worth and taking responsibility for our choices.

Circles vs. Lines

Berry's cyclic view of human life and experience in the world contrasts to a typically linear, western view. The linear view looks at the world and our choices from a timeline of assumed progress in which resources are used up and discarded as no longer useful.

The organic waste of our society, for which our land is starved and which in a sound agricultural economy would be returned to the land, are flushed out through the sewers to pollute the streams and rivers, and finally, the oceans; or they are burned and the smoke pollutes the air; or they are wasted in other ways.

The irony of this is that what the system needs for health, we have, through our systems, turned into a liability and a problem to be solved. In the cyclical model, we use something we need for a time and then return it back to where we got it, in a form that is needed and used by another part of creation—for instance, manure that increases soil fertility, nurtures plants, and is eventually eaten by animals, including us. As Berry says, the cyclical view is efficient—nothing is wasted—while the linear approach uses up resources which are turned into waste products that we have no use for.

The perspective I have on leaves that fall from the trees in my yard has been formed from this cyclical viewpoint. I value finding ways to return the nutrients a tree has expended into leaves back into the soil through mulching my garden. Gradually, I have seen the poor soil that was left when the builders of our home scraped off the top layer of soil, become more healthy than it was when we first moved in. To merely throw the leaves into a garbage pile is breaking up the cycle that naturally occurs and wasting valuable natural resources.

Consumerism vs. Stewardship

The idea of ecology is central to Berry's thought. We can either be someone who contributes to the health and ecology of the whole system or who wastes resources, creates waste as a result, and ducks responsibility for both of these actions. At the root of the issue is how we see ourselves. Consumers are those who use up resources (consume). That identity stands in contrast to seeing ourselves a contributing member of the ecological system, one who is part of the ecology of a place, restrains from using more than they need, and sees how they live as related to how other things live around them.

The way out of the wastefulness of consumerism obviously cannot lie simply in a shift from one fashionable commodity to another commodity equally fashionable. The way out lies only in a change of mind by which we will learn not to think of ourselves as consumers in any sense. A consumer is one who uses things up, a concept that is alien to the creation, as are the concepts of waste and disposability. A more realistic and creative vision of ourselves would teach us that our ecological obligations are to use, not use up; to use by the standard of real need, not of fashion or whim; and then to relinquish what we have used in a way that returns it to the common ecological fund from which it came.

According to Berry, it comes down to the way we look at ourselves in relation to the land and the rest of creation. If we believe we own it in a way that gives us the right to extract whatever we want from the land, other people, other creatures, in whatever way we believe most profitable, we will behave differently than if we take a long view. A long view sees ownership as temporary, seeing both who came before us and who will come after us, with wider values than just what seems most expedient at the moment.

So far as I know, there are only two philosophies of land use. One holds that the earth is the Lord’s or it holds that the earth belongs to those yet to be born as well as to those now living. The present owners, according to this view, only have the land in trust, both for all the living who are dependent on it now, and for the unborn who be dependent on it in time to come... The standard of this sort of land use is fertility, which preserves the interest of the future.

The contrast to this is a much narrower, self-centered view.

The other philosophy is that of exploitation, which holds that the interest of the present owner is the only interest to be considered. The standard, according to this view, is profit, and it is assumed that whatever is profitable is good. ... The earth, these people would have us believe, is not the Lord’s nor do the unborn have any share in it.

Although Berry names specific exploiters in his essays, he sees all of us, not just strip-mining companies and governmental agencies, as the ones who are at fault. We are all responsible by the choices we make when we prioritize convenience and comfort and the wish to avoid labor; these choices are what create a market for products that harm the earth's ecology.

We have to begin to distinguish between the uses that are necessary and those that are frivolous... We must see the differences between the necessity of warmth in winter and the luxury of air conditioning in the summer, between light to read or work by and those “security lights” with which we are attempting to light the whole outdoors, between an electric sewing machine and an electric toothbrush.

Our lives are full of choices, and Berry encourages us to see those choices as significant and empowering.

The change I am talking about appeals to me precisely because it need not wait upon “other people.” Anybody who wants to can begin it in himself and in his household as soon as he is ready—by becoming answerable to at least some of his own needs, by acquiring skills and tools, by learning what his real needs are, by refusing the merely glamorous and frivolous. When a person learns to act on his best hopes he enfranchises and validates them as no government or public policy ever will.

Immediately after I finished A Continuous Harmony for the first time, I gathered the fallen apples from my parents' trees and made my first batch of canned applesauce, with the first jar going to the friend who had given me the book. It was an old-style apple variety and my friend claimed it was the best applesauce he had ever eaten. This was a small action, but one that propelled me forward, partly because it was a signal to myself that I wanted to take the ideas seriously. In all the years since, it is rare that I don't make and can my own applesauce. It is small actions, like making our own applesauce (so much more flavorful than the store-bought kind!), that help us shift our perspective and practice, and teach us how to more truly value the earth and the abundance it provides as a gift intended for all people, in all times and places.

There is much more I could say about the work of Wendell Berry, but instead I invite you delve into it further on your own, either for the first time, or as a refresher course. He doesn't have his own website, but you can learn more about him here.

Reflection Question: Can you point to some resource that particular spurred you on to a life of ecological discipleship? Has there been a ecological practice that has been particularly meaningful or significant to you?

Feel free to leave a comment below or contact me directly at louise.conner@circlewood.online.

Louise

Want to learn more?

Find out more or support our parent organization by clicking below.