A hated borderland, separating the two halves of Germany, became the seedbed for a project of ecological diversity and connection. Because it was mostly abandoned, this historical place of cruelty and oppression made possible the German Green Belt, which stretches from north to south across the entire united country of Germany.

Roots in History

When the border between West and East Germany was opened, and celebratory crowds swarmed over the Berlin Wall, I remember watching them tear it apart with hammers and picks. It was the end of a hated symbol of a hated reality—the separation of a single city into two parts.

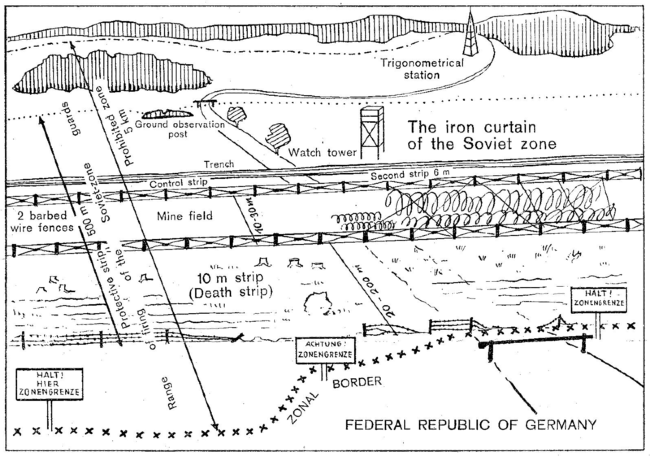

I don’t remember as clearly the fall of the “inner German border,” which, 96 miles west of Berlin, separated the bulk of East Germany (the German Democratic Republic) from West Germany (the Federal Republic of Germany) with a much longer set of fencing and stretched 866 miles from the Baltic Sea to Czechoslovakia. Built earlier than the Berlin wall (in 1949 instead of 1961), it was wasn’t completely abandoned until July 1, 1990.

During the border closure, East Germany used electrified barbed wire fences, guard towers, heavily armed guards, and mine fields to stop emigration, creating a stretch of uninhabited land known as the “death zone,” where East German patrols shot those trying to cross into the West.

When the border opened and people crossed the border to visit and relocate, many were eager to incorporate this border land into their fields and infrastructure systems, both for economic reasons and to eradicate the bad memories of the border. But there were also some who believed that the "death zone" contained something valuable that was worth saving.

The border's “no-man’s land,” left largely undisturbed throughout the years, had become a haven for flora and fauna. In a country and region of heavy industrialization and development, this pocket of thriving nature was unique.

People like Kai Froebel noticed it. "When I was 14, I started to record the bird species in the area,” says Frobel, an ecologist who grew up on the West German side of the border in the 1970s. “I noticed very quickly that the majority of the rare species, like the whinchat, nightjar, corn bunting, were all breeding in the 'death strip' of the GDR, of all places.”

Frobel publicly documented this surprising wildlife haven, and later began working for BUND, (Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz Deutschland) which became part of the larger Friends of the Earth, founded in 1975. From the western side of the border, BUND saw an abundance of bird and animal species, thriving in the hostile environment, and, in the 1980's, began to buy and protect land along the western side of the border.

In December, 1989, only a few weeks after East Germans first broke through the Wall in Berlin and then through the inner-German border installations, BUND organized a meeting of 400 West and East German environmentalists. From that meeting came the Green Belt Resolution of Hof (Germany) claiming that the border area “should be protected as the ecological backbone of Central Europe.” It was passed unanimously and signed by more than 300 environmentalists. Since the border was universally referred to as the “Death Strip” and most Germans wanted to erase anything that stirred bad memories of the past, this was a courageous (and not completely popular) position to take.

In order to prove the value of the land, BUND and the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (BfN) inventoried the ecosystems and species along the Green Belt. Teams of ornithologists, botanists, and entomologists walked hundreds of miles, recording and collecting data from locals in each area. More than 1,000 species of birds, mammals, plants, and insects from Germany’s Red List of endangered species were identified, along with 146 different types of habitat, 46% being on Germany's Red List.

Government Action

Even with this proof of the land's value, setting it aside rather than using it for economic purposes such as agriculture, was a hard sell to many. Between those who wanted to erase the painful memories of the past and those who were struggling economically and saw this as an opportunity to increase their financial stability, moving the idea forward was difficult, especially with deep divisions between environmentalists and farmers.

The government moved the process along by purchasing and setting aside large tracts of land. In 2010, the process of transferring federal land comprising part of the National Natural Heritage in the Green Belt free of charge to the various states (Länder) and their nature conservation foundations, was completed and in 2015, Angela Merkel designated the Green Belt as part of Germany's National Natural Heritage.

Incorporating the Past

Most evidence of the inner German border have been dismantled, but those that remain are reminders of the cultural and historical importance of the space. Museums and memorials along the old border commemorate the division and reunification of Germany, with some elements of the fortifications left standing. A hiking trail at the Borderland Museum Eichsfeld (pictured below) leads along preserved parts of the inner-German border and features information panels about the border.

The art installation pictured below was created in 2010 and placed next to the bike path as a reminder of the past trauma that happened here. These efforts remind visitors that this is not just an amazing ecological space, but is also a significant, though dark, piece of German history.

Ecological Importance

The Green Belt is now considered the backbone of the green infrastructure and biodiversity network in Germany. Except for high mountains, it passes through all types of German landscapes, from low mountain ranges to north German lowlands.

Red-Backed Shrike, Black Stork, Whinchat

The diversity of the landscape makes it an important refuge and home to many plant and animal species: rare orchids like the lady's slipper, the clubtail dragonfly, the marsh fritillary, the whinchat, the red-backed shrike, the black stork, the kingfisher, wildcats, and the otter, to name just a few.

More than 80% of the former inner-German border is now part of that protected green belt.

Beyond German Borders

Due to their progress toward a German Green Belt, environmentalists began to envision a larger European Green Belt, along the larger "Iron Curtain" of the former Soviet states. All along the former Iron Curtain, similar pockets of wilderness had been left untouched. The forests of Norway, Finland and Russia sheltered elk and bears, and to the south, in the mountains and lakes of the Balkans, lynxes and pelicans thrived.

After a first meeting about a European Green Belt in 2003, a working group was formed to coordinate its implementation. The European Green Belt now stretches for 7,767 miles along the borders of 24 states, from the Barents Sea in the north to the Adriatic and the Black Sea in the south.

As climate change affects migration patterns, these green belts have become an escape route for species fleeing northwards to cooler areas. “These corridors and stepping stones, they allow species to maintain their strongholds and to exchange genes, and to migrate,” says Aimo Saano, who works for an agency managing core areas of the Finnish segment of the European Green Belt. “They create the complex ecosystems that should be there." “As we know from densely inhabited Europe, this is the obvious danger: that ecosystems have been minimized and cut into small pieces, separated from each other.”

Being Ready

To watch the border fall in Germany was an amazing experience. One day it was there, and would be seemingly forever, and the next day everything had changed. Without people already aware of the ecological promise of the "death zone" who cared enough to act quickly when circumstances changed, an irretrievable opportunity would have been lost along with the border that preserved it. The ecological treasure that had grown within those long decades of darkness would have been dismantled as quickly as the wall was. Staying informed, being alert, and caring enough to act on behalf of things you care about may yield opportunities to make a difference beyond what you could ever imagine.

Reflection Questions: What do you do to stay informed, alert, and caring when the ecological situation around you seems dire?

To leave a comment, click in the comment box below, or email me at info@circlewood.online.

Louise