A few days ago at a Circlewood event, a friend reminded me of a free phone application called Merlin (from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology) that identifies and records bird songs as heard through the microphone of your phone. (Thanks, Joe!) The Merlin app is based on the eBird citizen science project the Cornell lab has built over the past 20 years and its database contains the world's largest catalog of bird sounds, sightings, and pictures. They welcome participation from people in all areas of the world since, although the database includes birds from many parts of the world, there are regions not yet covered by the app which they would like to expand into.

This reminder happened to coincide with a desire to incorporate intentional “nothing” time into my daily life. Early Monday morning, the first morning after making a commitment to create uncommitted time within my days, I was sitting on our front steps, listening to the vociferous early-morning birdsong of my neighborhood, when I thought of the Merlin app. I had downloaded it onto my phone some time ago, but had never used the birdsong identification part of it. So, I retrieved my phone from inside the house and opened the sound identifier on the app.

For the next five minutes, I sat on the porch enthralled, listening to the multitude of bird melodies, watching as Merlin disentangled and highlighted the unseen strains of the raucous cacophony all around me: American Robin, Spotted Towhee, Chestnut-backed Chickadee, Bewick’s Wren, Dark-eyed Junco, Purple Finch, Northern Flicker. I was fascinated by the names of the bird choir that popped up on the screen—a mixture of birds I regularly saw and recognized in the neighborhood around me, and more timid and less visible ones which I didn’t remember ever seeing. The names ran by: Bushtit, House Finch, Chipping Sparrow, Song Sparrow, Brown Creeper, Golden-crowned Kinglet. Time passed swiftly and soon I was informed that I had been recording for 10 minutes—Did I want to keep recording? Cedar Waxwing, European Starling. With new birds continuing to appear on the screen and others being highlighted as they started up their song again, how could I stop? Red-breasted Nuthatch, Black-capped Chickadee, Black-headed Grosbeak.

Eventually, I put down the phone to do something else, only to pick it up again and walk through the house to the backyard, curious if there would be different refrains sounding in that, more forested, space. I spent a large portion of the morning walking back and forth between the front and back of the house, trying out different spots in each to see how my placement affected the birds being identified.

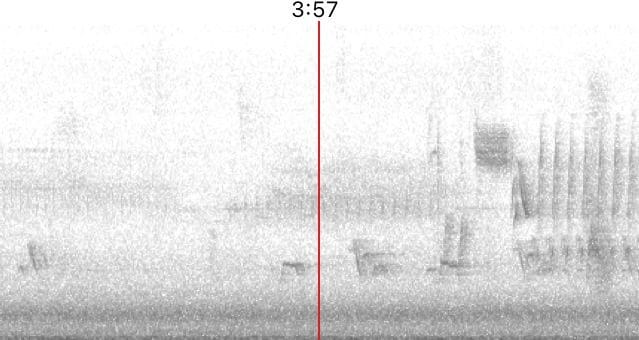

I became fascinated with the moving graph showing a live representation of the birdsong being recorded. The patterns and pitch of each song became more apparent as I not only heard the song, but also visually saw the trills, lines, rhythms, and durations shown on the screen, with the patterns of the louder voices becoming darker and higher and lower pitches showing up on different levels of the graph.

The red line in the birdsong graph above shows the sound pattern at the 36:30 mark in the recording, which is when a Bewick's Wren began its song. One of the quieter voices recorded, the song of the Bewick's Wren is still captivating to listen to. By beginning the recording around 36 seconds in, you can both aurally and visually experience its song. The wren repeats its song at 52 seconds, at one minute, and at one minute, 14 seconds. After listening to its song (amidst the other birdsong) in those four places, do you begin to recognize its voice? Are there other places in the recording where you can begin to pick out its song among the other voices?

The layers of birdsong and how the songs and calls interact with each other became more evident when I could both hear and see the songs and patterns. I noticed how much the American Robin had to say, with its various calls and songs, at times monopolizing and overshadowing the other birdsongs. I noticed how some bird songs seemed to always follow the songs of another type of bird, seemingly in response.

Hearing and recognizing these unseen voices expands my understanding of the scope of other creatures living on this land beyond what I am able to see with my eyes. (When I hear the owls hooting, I know our wild rabbit population will soon experience a sudden decrease). Knowing what bird species sing in the morning in my neighborhood can clue me in to who might be nesting in the area, which could in turn affect what I plant in my yard if I am trying to provide habitat for other creatures.

Although I have watched birds in my yard all my life, it seemed as if my knowledge of my bird neighbors grew dramatically in just one morning. Expanding my knowledge beyond a very limited number of bird calls—such as the robin, the towhee, the junco, the flicker—and recognizing a greater proportion of the birds who are giving voice around my home, helps me to appreciate more fully the diverse community I live within. Since many of these birds will never come to a bird feeder, and may never be seen by me, hearing and knowing their songs expands my ability to know who my neighbors are, and, I hope, to become a better neighbor as a result.

Reflection Questions: Do you use other senses besides sight to know what other creatures are around you? How much time do you take to become acquainted with your nonhuman neighbors?

Feel free to comment below or contact me directly at info@circlewood.online.

Louise