Sometimes, you can get a clearer picture of something by taking a few steps back for a more comprehensive view of what you're looking at—and can see how all the parts fit together. But, sometimes, there are things you can only see if you step in closer, focusing on a single small segment of the bigger whole. By focusing on the tiny, we may gain valuable insights of the large that we cannot gain otherwise.

Karl Blossfeldt, 1865-1932, started work as an apprentice in a foundry where he formed iron into plant motifs, traveling far afield to collect specimens which he created casts from. But later, at the Berlin School of the Museum of Decorative Arts, as he was trying to teach his students about the patterns and designs to be seen in nature, he created the artistic work that would be his most influential legacy.

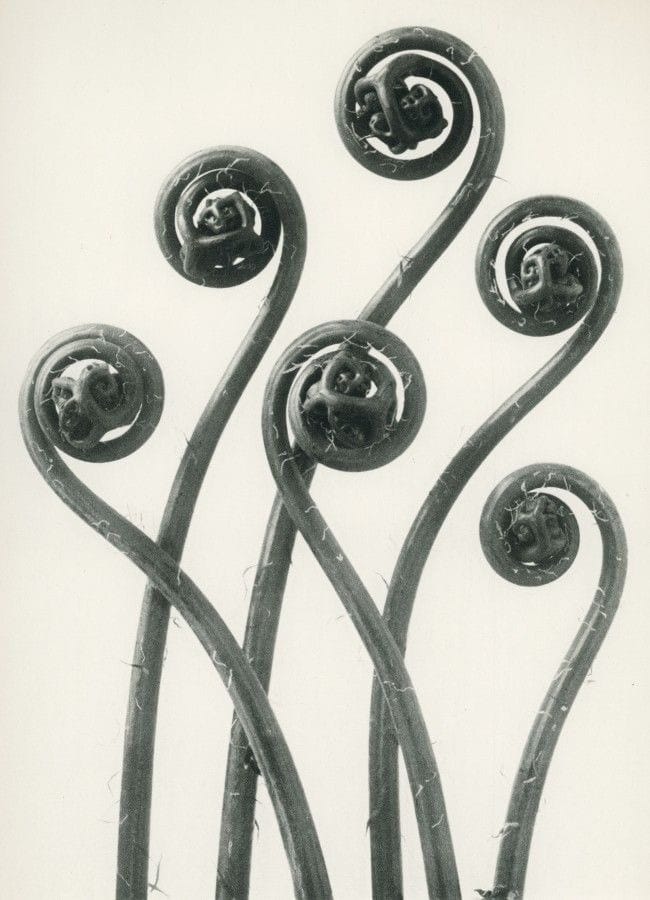

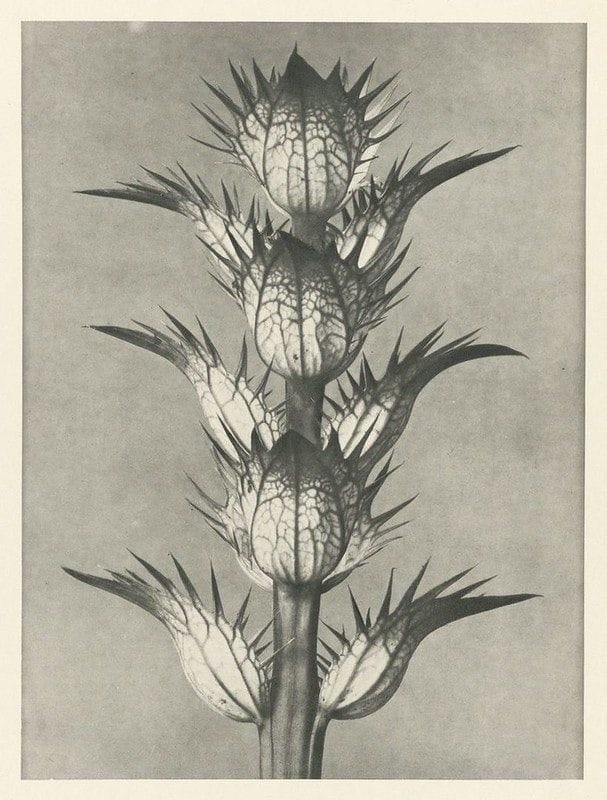

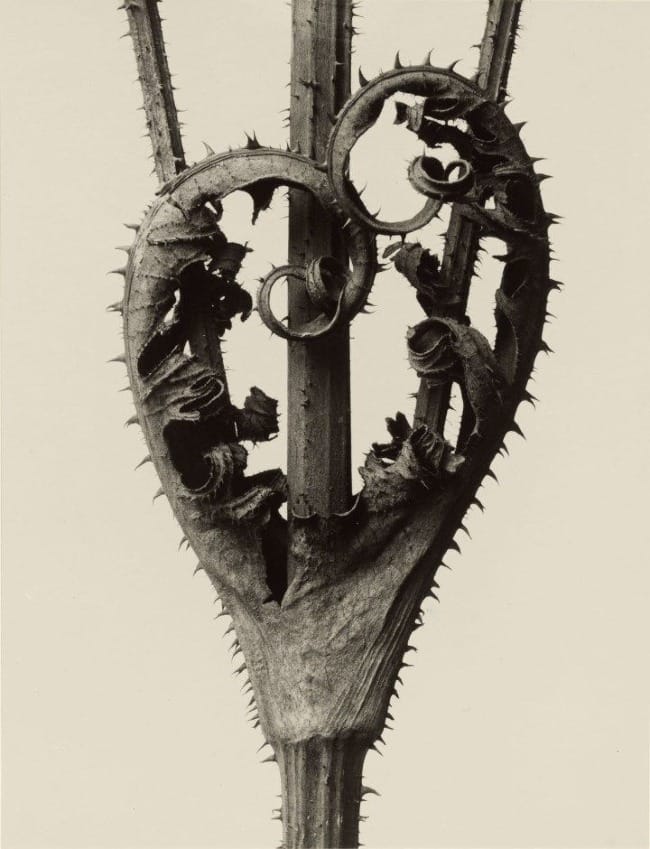

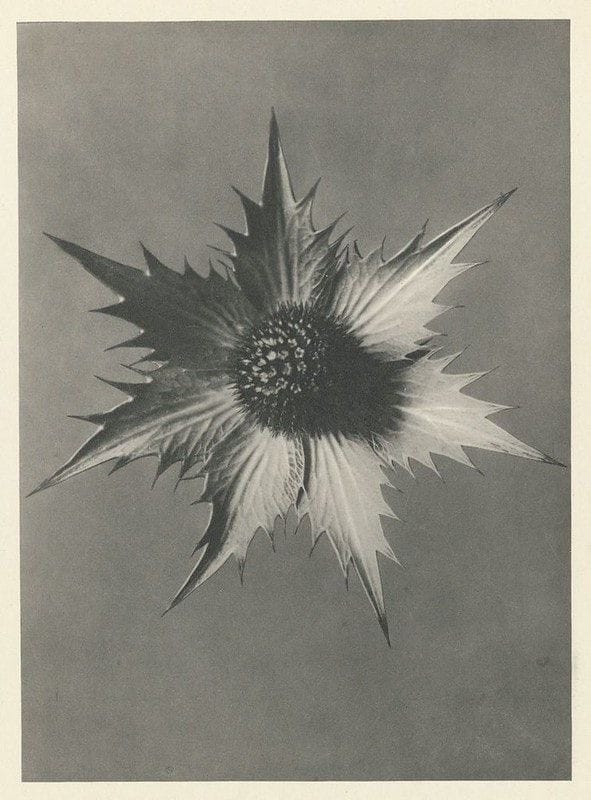

Blossfeldt believed that the foundation of contemporary art should be based on the inherent beauty present in natural forms, a beauty that could be seen through the tiny details of structure and design—in other words by coming very, very close to those natural forms, but even then there were details that would not be visible to the naked eye. His envisioned solution was to capture those details through macro photography, which he would then use as teaching aids with his students.

As he wrote in a 1906 letter to the school's director:

Plants are a treasure trove of forms — one which is carelessly overlooked only because the scale of shapes fails to catch the eye and sometimes this makes the forms hard to identify. But that is precisely what these photographs are intended to do — to portray diminutive forms on a convenient scale and encourage students to pay them more attention.

However, when he requested funding for this photography project from the institute, the request was denied. Instead of abandoning the project, he persevered, building his own camera with a meter-long bellows, enabling him to magnify tiny details of the thing he was photographing.

In other words, he went to extraordinary lengths to create his own teaching tool. Everyday flowers and weeds, which would normally be overlooked, became exotic through the lens of his camera. Over the years, he amassed thousands of these photographs, using them as models for teaching his students.

Eventually, his work drew the notice of others, including Karl Nierendorf, a gallery owner who first created a solo show of Blossfedt's work and later produced a monograph of his photography titled, Urformen der Kunst (Art Forms in Nature). The book was hugely successful and was followed by Wundergarten der Natur (The Magic Garden of Nature), in 1932. The clarity, precision, and objective view in his pictures, and their presentation as a reference source for essential forms in art and architecture, made his work very popular in the world of photography.

Finding the Divine Artist in the Details

In addition to the patterns and structures that Blossfeldt's pictures enable the viewer to see, Blossfeldt's approach to the natural world around him has further lessons we can learn from.

To begin with, paying attention to created art is essential if we are truly honoring the artist who created it. If someone says they love Van Gogh, we would assume they pay attention to the work he has poured himself into and is a reflection of him. Since the work of this creation was made by the pouring of God into it, an essential way to honor God is to honor this work God is poured into.

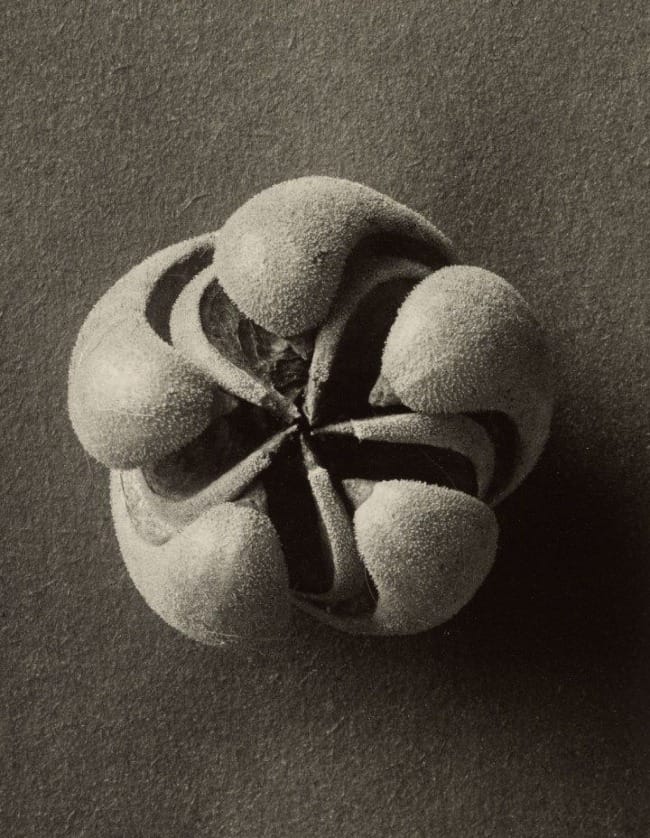

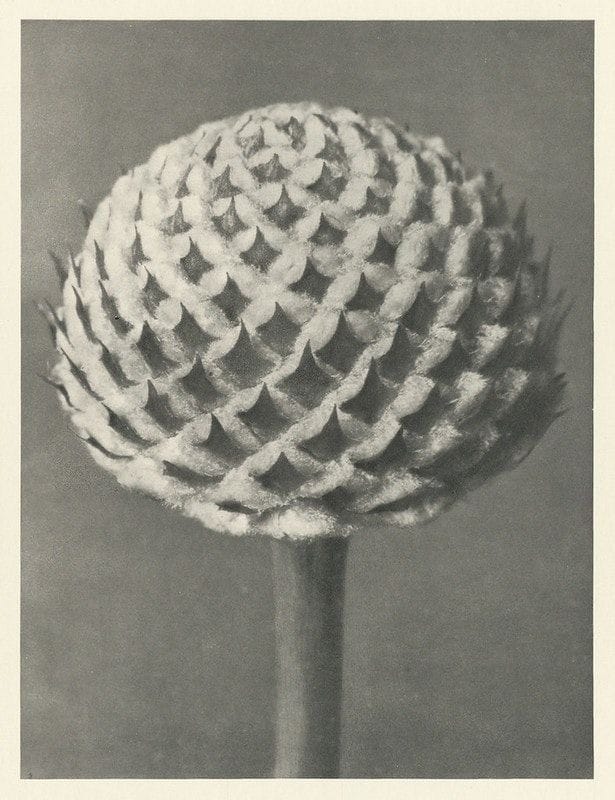

Secondly, if God designed this universe, I believe there are things we can learn about the Creator through close observation of what God has made. I am personally amazed by the variety of ways that plants propagate themselves. Sometimes when I find a particularly interesting seed pod, I keep it on the dashboard of my car and have dreams of creating a wider collection of propagation structures found in plants: pods, cones and all the rest. It fascinates me that even within a specific type of propagation, such as cones, there are so many differences, each clever and fascinating and beautifully intricate.

For me, this variety and beauty tell me something about God. I will even go so far as to say that when that variety decreases, through extinction or replacement with homogenous flora and fauna, the result is a more limited representation of God. In the same way that each individual painting reflects something original about the painter, or each poem is a unique reflection of the poet, I believe each part of creation shows us a view of God the Creator. But in the tiny bits of art around us, we have to get very close to see what that delicate work can show us.

In light of that, I invite you in the next couple of weeks to honor the artist of this world by imitating Karl Blossfeldt—in addition to stepping back to see the whole picture, make an opportunity to step in close to see the very specific details of something that is right in front of you. It could be a feather, a leaf, a knuckle.

As an added invitation, take a picture (or create a drawing) of something that intrigues you when you observe it up close, rather than from a distance. Does anything catch your notice? Or fascinate you? Or delight you?

Blossfeldt's pictures were primarily not of the exotic—they were of the plants that were in the overgrown lot next door. It was only by coming in close and looking intently that the exotic contained within them was revealed. So, step in close, look until you see something in the familiar that you haven't noticed before and take note of it, and, if you are willing, share it with us! Send it in to me by April 25th and I will include it in a "Readers Share" post that week. I already have a favorite kind of seed pod in mind...

I end with these favorite lines from William Blake, which, like Blossfeldt's photography, encourage us to look for the big within the small.

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

You can see more of Karl Blossfeldt's work here.

Feel free to contact me directly at info@circlewood.online.

Louise